When discussing Bunker Hill, it is common currency to assert there were no survivors. Shades of the SS Yongala. KLM 4805. The Benwood Mine. And you’d be right to assert so. Granted, should we consider the Hill’s boundaries Hill/Fifth/Figueroa/Sunset then yes, remarkable vintage structures do exist therewithin (e.g. Subway Terminal, the Edison Bldg, and Curlett & Beelman’s 1923 Savoy Garage, oldest extant garage in Los Angeles) but they don’t connote “Bunker Hill of yore” the way a wooden Victorian house does, do they? And someone—not you, of course—always says “but they moved those houses! They’re at Heritage Square!” Well, yes and no: “they” moved a grand total of two, which burned in short order (as discussed in Bunker Hill, Los Angeles and in Bunker Noir, available here).

But now, remarkably, there has come to light a lone survivor. It’s the Vesna Vulović of Bunker Hill houses.

This discovery was made known to me by the esteemed Charles J. Fisher. As in, I was minding my own business the other day when I got a phone call from my buddy Charlie. I answer and he intoned “are you sitting down?”

And who is Charlie Fisher? Of the 1200+ Historic Cultural Monuments in Los Angeles, Charlie has written the landmark nominations for a vast number. He is, after all, Historian4Hire. I’ve known Charlie for about twenty years and I’ve learned when he telephones, it’s always something interesting.

So Charlie calls and tells me he’s working with a woman who’d purchased an 1880s house on Edgeware, wanted to Mills Act it, and had hired him to do the research. He discovers that her house had not only been moved to the spot from Toluca Street—but above and beyond that, it had been moved there from Bunker Hill. And not some outerlying part (no, the Weller House does not count as Bunker Hill), but smack dab from the thick of it. And my jaw drops. This would make it the one and only bona fide existing Bunker Hill house.

This is the story.

It begins with Block 4 of the Beaudry Tract, bounded by Fourth, Olive, Third and Charity Streets (you know Charity Street as Grand Avenue, so renamed in February 1887).

This was part of land purchased in 1867 by Prudent Beaudry, and subdivided into building lots at his request by surveyor George Hansen. Lots didn’t exactly sell like the proverbial hotcake—but construction picked up as folk funneled into town fueled by our 1876 connection to the transcontinental railroad and the 1884 publication of Ramona.

Our discussion today involves Lot 7 of Block 4.

PART I: THE BUILDER

John Wesley Ellis, Ohio-born in 1842, served in the 149th Regiment, Ohio Infantry during the War, after which he becomes a Presbyterian minister in Lincoln, Neb. Ellis relinquished the pastorate of the First Presbyterian Church there in 1874 to make California his home, initially at Chico. In 1877 the Presbyterian Synod of the Pacific Coast selected Ellis to establish Presbyterianism in the then-pioneer field of Southern California. Rev. Ellis, D.D., heads to Los Angeles with his wife and two children; he’s the first Presbyterian pastor south of San Francisco, and founded Los Angeles’ First Presbyterian Church. He ministered from a little brick building on Fort Street between Third and Fourth, until 1882 when he oversaw construction of the Charles W. Davis-designed First Presbyterian Church at the southeast corner of Fort and Second Streets. (Edit: Ellis was not the first Presbyterian pastor in Los Angeles; that title belongs to Rev. James Woods, who held a service in a carpenter shop in November 1854. It was a challenge to maintain services in lawless Los Angeles, though. Protestants attempted to build a church in 1862 at the SW corner of Temple and New High Streets, but the work was abandoned halfway. Ellis’s claim to fame is that under his ministry, services were held regularly, the congregation solidified, and the magnificent church was built.)

About the same time the papers are full of much talk regarding Ellis up on Olive near Third: in January 1882 the Times noted that W. R. Norton had designed a $3,000 residence for Ellis on Olive Street; in February 1882 it is announced that Thomas Stovell had just completed the millwork for Ellis’ “elegant residence on Olive Street”; in March 1882 the Times detailed the house going up on Olive for Ellis; beginning in July 1882 it is mentioned on some number of occasions that Ellis is ensconced in his new residence on Olive between Third and Fourth (in fact he performed funerals therein); and yet in April 1883 it is noted again that a two-story nine-room residence for Rev. J. W. Ellis was in the works at architect Norton’s office, and mention is made in July 1883 that this new Olive Street house of Rev. Ellis was under construction.

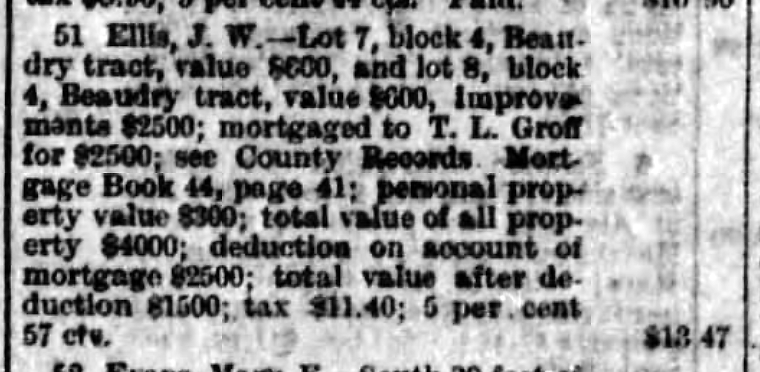

So you’re saying well, that’s rather odd, so Ellis built a house, and then he built another one? Apparently that’s just what he did…he owned both Lot 7 and the contiguous lot to the north, Lot 8, as shown in the “Delinquent Assessment Book of Los Angeles City, Assessed to All Known Owners or Claimants:”

As such, “our” house on Lot 7 was either the first house, the W. R. Norton-designed home built in the spring of 1882, or the W. R. Norton-designed house discussed as under construction in the spring of 1883. Unfortunately the City Directories aren’t terribly helpful as to which one he lived in, in ’82-3-4, because at the time the street wasn’t numbered yet:

By the time Lot 7 gets its actual address—215 South Olive—in the 1884-85 Directory, Ellis has moved out of whichever of the two he had built (either Lot 7/215 South Olive or Lot 8/211 South Olive) to go off and live in his namesake College. 215 South Olive is listed as the residence of one D. M. Shaffer, a laborer for the Southern Pacific Railroad. Presumably it’s a rental at that point before Ellis sells the place, and it becomes something else altogether.

PART II: SISTER MARY’S HOSPITAL

Many who came to Los Angeles did so, famously, for relief of their ills. Basking in the curative climate would relieve them of the catarrh, or so went the promises of the boosters. Trainloads of “lungers” after the “California Cure,” clutching Nordhoff’s California: for Health, Pleasure, and Residence (which contained a special section for consumptives) checked themselves into Sanatoriums, Climatoriums, Inhalotoriums, and all other manner of hospital and institute.

Taking the clean, dry air up on the Hill, above the effluvial miasmata of the city, seemed a logical endeavor. Thus a hospital high on the healthful heavens of the hill was just what the doctor ordered.

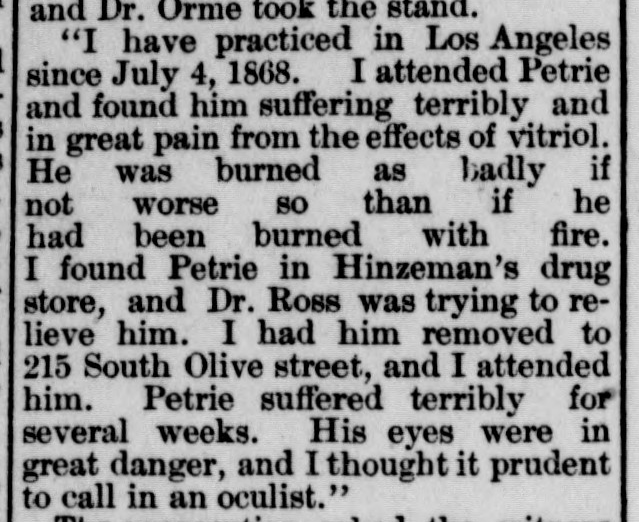

With the street newly numbered, our Lot 7 of Block 4 now 215 South Olive Street, and with Ellis newly having moved to Crown Hill, Anglican nun Sister Mary Wood turned her eye to the structure up the hill. In November 1885 she converted the house into the nine-bed Los Angeles Hospital and Home for Invalids:

Episcopalianism had made great strides since the 1855 foundation of St. Paul’s parish, the first Episcopal organization in Southern California. St. Paul’s Protestant Episcopal Church had, in the spring of 1883, built their wonderful Burgess J. Reeve-designed church on Olive Street facing Los Angeles Park; come December 1885, three blocks up Olive their hospital was up and running:

Eventually, the Diocese of California (there would be no Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles until 1895) decided it was time to formally assume control of Sister Mary’s infirmary. The Church filed Articles of Incorporation for St. Paul’s Home for Invalids in late August 1887; in October the Olive Street patients were transferred about six blocks north into the new facility, a large leased houseon Sand Street just west of the high school, in the Fort Moore area of Bunker Hill.

Having been gifted $4,000 ($116,843 USD2020) to fund the move—from good samaritan Annie Crittenden Severance—St. Paul’s elected to rename itself Hospital of the Good Samaritan, in 1895. It moved to Orange Street (Wilshire Blvd) in 1911, and in a bit of nepotism, hospital president Bishop Joseph H. Johnson had his son design the new hospital of 1926. Fortunately, his son was none other than Reginald D. Johnson. The hospital is given a major addition in 1953, has a new hospital added in 1976 and is renamed Good Samaritan Hospital. It is where Inez Millholland, Jean Harlow and Robert F. Kennedy died—it is routinely listed among America’s greatest hospitals—and it all began in that house on Bunker Hill.

PART III: THE VAN DYKES

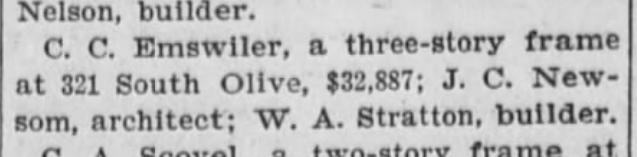

Walter Van Dyke—former State Senator, former United States District Attorney for California—moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles in 1884 to form the law firm of Wells, Van Dyke & Lee and sit on the Superior Court bench. In 1887 he was living at the NW corner of Boyle and Stevenson Avenues in Boyle Heights. His office was in the Baker Block downtown; that’s a heck of a daily commute from BH. So after the invalids move out of 215 South Olive, Walter, his wife and five children (including son Edwin) move in; they are listed in the directories in 1888. A Los Angeles city ordinance renumbering all street addresses went into effect in December 1889; 215 South Olive thus became 321 South Olive.

Now then, let’s take a look at the house in question!

Here we are atop City Hall’s tower, on Broadway between Second and Third, looking west toward Bunker Hill:

PART IV: THE MOVING HOUSE

And what became of the house? Walter Van Dyke, after having been elected Judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1888 and 1894, was in 1898 elected a Justice of the Supreme Court for a period of 1899-1910, and so departed Los Angeles, moving to Oakland (he serves half his term, felled by pneumonia in 1905). From 1899 on it was home to various boarders, e.g. Albert G. Bartlett, President, Bartlett Music Company; Augusta P. Gehring, physician; Henry Howard, manager, American Mining Company; and other upstanding types.

This goes on for about five years until:

Wildy did indeed sell his high and sightly house—one of the best sites in the city for modern hotel!—because a Mr. Charles Clayton Emswiler purchased 321 and proceeded to erect a modern hotel (eponymously named The Ems). Granted, he clad said modern hotel in the romantic, olde-tymie charm of the Missions, but still.

Once upon a time, however, we weren’t quite so cavalier about tearing a good old house down. Rather, we would move them.

Deputy Sheriff Edwin Herbert Hutchinson lived at 134 Toluca Street. The lot beside him, at 130, was empty; in September 1905 he poured a foundation for a two-story frame residence, called a local house mover and had 321 brought on over.

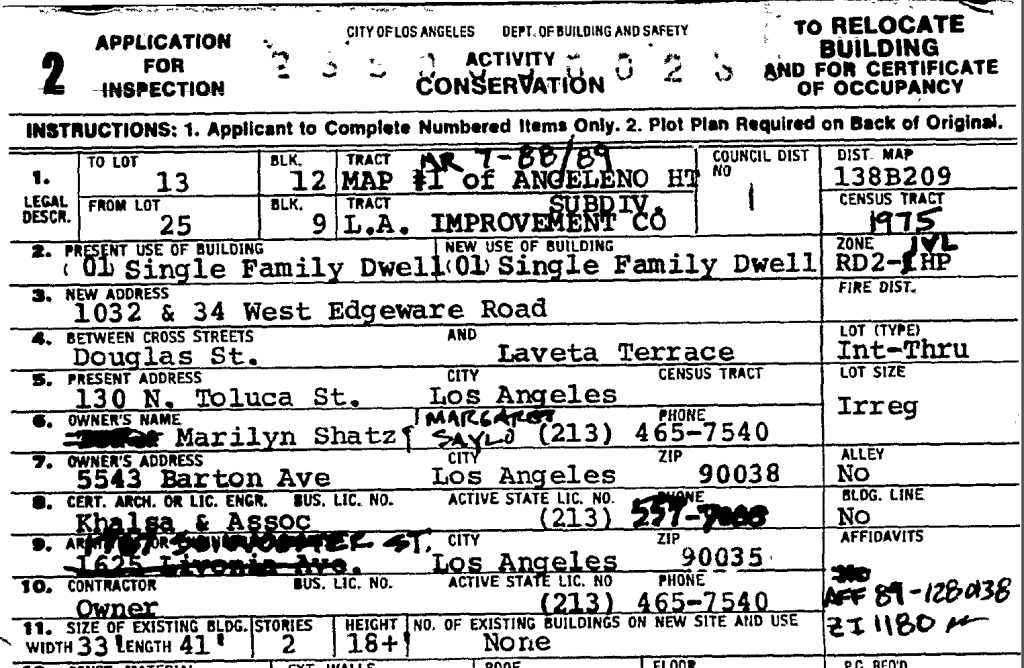

The house sat there on Toluca minding its own business until December 1989, when picked up and moved again:

And it’s been sitting quietly on Edgeware these last thirty-some years until recently sold and rediscovered as the last remaining house from Bunker Hill. Let’s take a closer look!

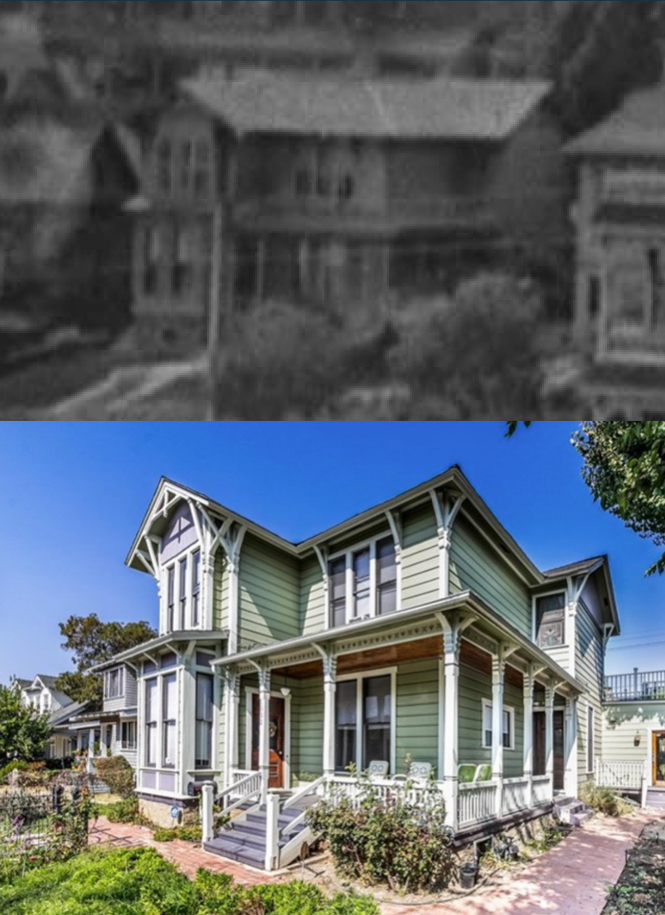

First off, a then & now comparison, obviously:

And that my friends is the tale of how a thoroughly Catholic Los Angeles got its first Presbyterian pastor, who hired the great William R. Norton to build a house (two, in fact) on Bunker Hill in the early 80s; how an Episcopal nun full of mercy & moxie built a Bunker Hill hospital, and from which we now have our venerable Good Sam; how a famed jurist came to make the house his home (I like to think it was because son Edwin was peering at the bugs of Bunker Hill, that he went on to become such an influential entomologist); how Edwardian-era apartment development (sooo Bunker Hill) tossed the house west into the Crown Hill area, until redevelopment displaced it a second time; and how it then found its forever home nestled among HPOZ’d friends in Angelino Heights, and subsequently rediscovered—brought to you here, today, for your edification and delectation.

I hope you have found this tale as interesting as I have; it was a thrill, pleasure and honor to unravel the house’s marvelous history. The new owner is excited to restore and possibly landmark it, and I will certainly remain in close contact with her to keep abreast of developments regarding its progress.

Viva Bunker Hill!

Nathan Marsak

Absolutely fascinating!

LikeLike

This makes me so happy! 💕

LikeLike

This makes me so happy. 💕

LikeLike

Sharing this with everyone. What a find!

LikeLike

This is the best news this year.

LikeLike

It’s a classic movie chase scene with destruction after the house. I just received your book as a present and love this follow up story. Bravo!!

LikeLike

From one Bunker Hill survivor to another, best wishes for a long and happy life.

LikeLike

My childhood home was big and beautiful on Carlton Way off of Gower and two blocks south of Hollywood Blvd was beautiful. The street itself is no more to make room for a gym expansion. Hope this home was moved. Beautiful mahogany everywhere. Our back yard went to the next street.

Thank you for sharing this his with me. Nice way to start my Sunday 😊

LikeLike

And it’s up for sale!

LikeLike