The story so far: In our introductory Part I, we saw how, when it comes to that fabled place called Chavez Ravine, what you likely believe is untrue, your having been fed the disinformation-heavy Regime Narrative. In Part II, you were given an outline as to the area’s location, genesis, and evolution. Today: a quick snapshot detailing life in the Ravine in the late 1940s, before it changed irrecoverably.

I. Small-Town Life

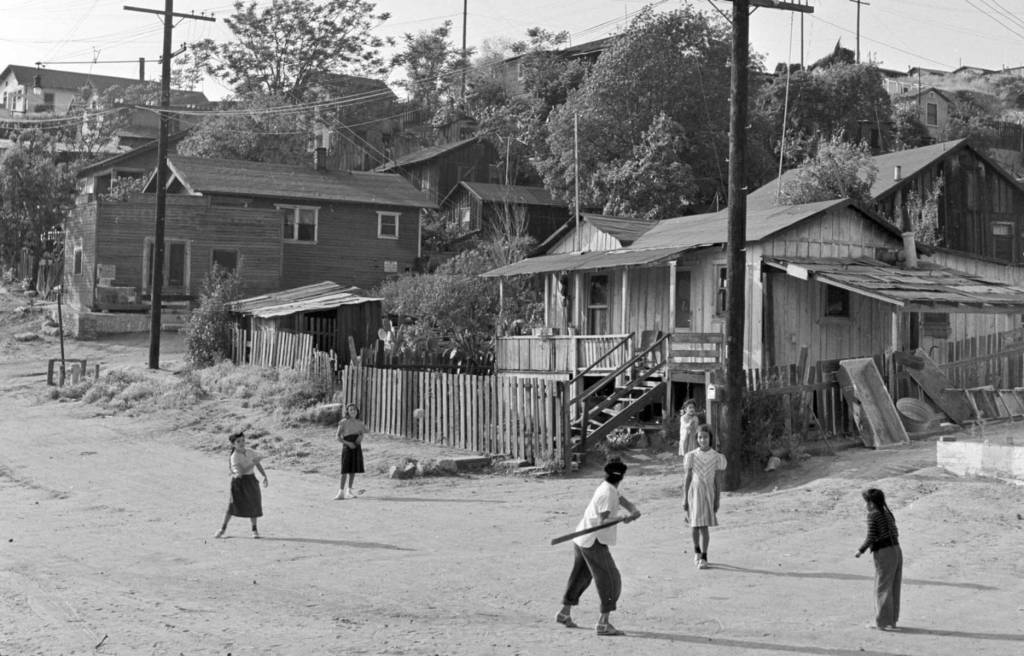

People idealize Chavez Ravine the same way they idealize Mayberry. Small-town life has the sort of community we long for, the village culture any city-bred American fetishizes. The unlocked doors. The fresh air. The nobility of people who worked hard, walked everywhere, and whose children rode bikes and played baseball in the streets. Slow-paced, tight-knit fellowships where folks grew their own food and shared with the neighbors.

But any real small town (unlike the fictional Mayberry) has its shadow side. The outdoor toilets, the high rates of disease, the xenophobia, spousal abuse and sexual assault, etc. etc. That notwithstanding, people still abandon Los Angeles for Mt. Airy, NC and Tipton, IN and Abbeville, AL et al. seeking a lost and mythologized ethos. The tale of Chavez Ravine’s simple life might attract those folk—irrespective of any right/left political dichotomy (“right wing” homesteading vs. “left wing” anarcho-primitivism, say)—who lean into what’s now called New Urbanism, whose golden thread traces back through Thoreau to Epicurus.

Of course, Chavez Ravine’s story is made all the more engaging to mythologize, since the area died not of natural causes—in the traditional way small American towns have often fallen to decline via industrial consolidation, agricultural automation, and other decay-causing elements—rather, Chavez Ravine was murdered, its residents displaced by the government. Heck, I wrote an entire book about a people displaced by the very same thoughtful and benevolent government. That I did, in large part, in an effort to separate fiction from fact…just as I’m doing here. (Don’t forget to come back on Thursday for Part IV, which will have all sorts of stuff about the friendly fellows from the government.) But for now, let’s just look at that Mayberry-flavored life in Chavez Ravine.

II. Normark Images Set the Scene

1950 was a pivotal year for Chavez Ravine, the year the Housing Authority began its work to remove all the residents. But immediately before that occurred, in late 1948 a 19-year-old photography student named Don Normark began to shoot the area in detail (it reminded him of the Swedish immigrant community he had lived in as a child). Though Normark spoke no Spanish, he was trusted by the residents, who welcomed his photography. Fifty years later, those images resulted in the 1999 book “Chavez Ravine, 1949: A Los Angeles Story.”

His images display in detail the people and lifestyle in Chavez Ravine. The text, having been taken from oral histories, is fantastic, but naturally flawed. There’s all manner of wild inaccuracy, e.g., that the neighborhood of Palo Verde was named by the residents after a particular green tree, and of course Normark’s book is the origin of the fancifully absurd myth that Palo Verde Elementary School had its roof torn off and was filled with earth.

Oral histories are valuable, in their way, but no scholar considers a single word valid without verification. Chavez Ravine residents, if in their 20s in the 1940s, were approaching their 80s when Normark conducted his interviews. I’ve worked on a number of oral histories with the elderly, and I can tell you from experience, they tend to make “cognitive leaps” to fill in gaps. And (for example, as is frequently the case of cops questioning suspects) memories become contaminated throughout the process of interviewing.

In any event, point being, great photos, so let’s look at a few, to get some neighborhood flavor:

III. Who were the people of Chavez Ravine?

Who were the people who lived in Chavez Ravine? One hears regularly that it was “all Mexicans who’d lived there for generations” but again, it was one generation, and it bears investigation, just how Mexican? The vast majority of its residents were native born: 70% born in America. That makes them Americans. Americans of Mexican descent, but at the end of the day, Americans. And of the 30% minority who were actually foreign-born, the majority of those people had become citizens. And of those foreign-born in Chavez Ravine, only 60% of those people were from Mexico. The other 40% were largely Italian, or from Central Europe.

You hear a lot about how people lost their homes, but most residents of Chavez Ravine didn’t actually lose their homes, because Chavez Ravine (like Bunker Hill) was primarily a renter’s community; only 40% of residents owned their homes. Specifically, of 1283 occupied dwelling units, 767 were rentals. Monthly rent averaged $17. Many of the homes had no plumbing, but outhouses. Not a single house in all of Chavez Ravine had central heat. The average value and/or cost of a home, $2000.

You will hear a lot about how the city wouldn’t pave streets, or pick up trash properly, which we’re often told is proof that LA was racist against Mexicans. But it was a rural area and simply remained so. Consider this—the neighborhood of Alpine, adjacent Chavez Ravine (specifically, tract 115 of the 1940 census), is quite revealing through the statistical abstracts: Alpine had a greater foreign-born population than Chavez Ravine, with a far greater number of Mexican nationals than all of Chavez Ravine. And yet Alpine, with more Mexicans than Chavez Ravine, had all the amenities of municipal services, paved streets, running water, regular trash pick up, street lights everywhere; and this was not an affluent area, but very blue-collar Mexican-American, and they had the same services as some bougie place like Hancock Park. As has been documented, many of the homes in Chavez Ravine were illegally built without permits, so the City apparently felt little need to pave streets, in what was a rural and renegade area (which is exactly what we find so appealing about the place).

III. Street Scenes of Small-Town Life

Note: the eight images in Section III, above, were shot by Leonard Nadel for the Housing Authority in 1950. They can be found at the Getty.

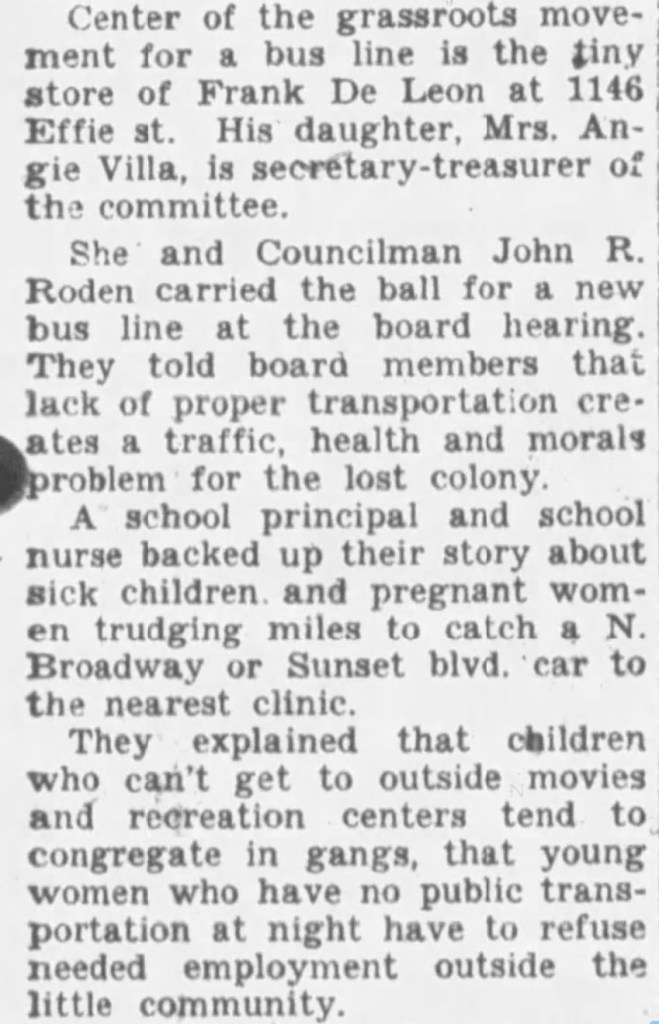

IV. Frank De Leon’s Market and the Bus Line

In 1946, the residents of Chavez Ravine banded together to get a bus line. Frank De Leon, who had a market at 1146 Effie, used it as HQ for the central committee to make this happen.

And such was life in Chavez Ravine: selling chickens, playing stickball, and getting a bus line!

And naturally, as I mentioned before, with yin there is yang, so, there must be a less savory side—

—which is an important part of understanding Chavez Ravine in all its nuance and complexity.

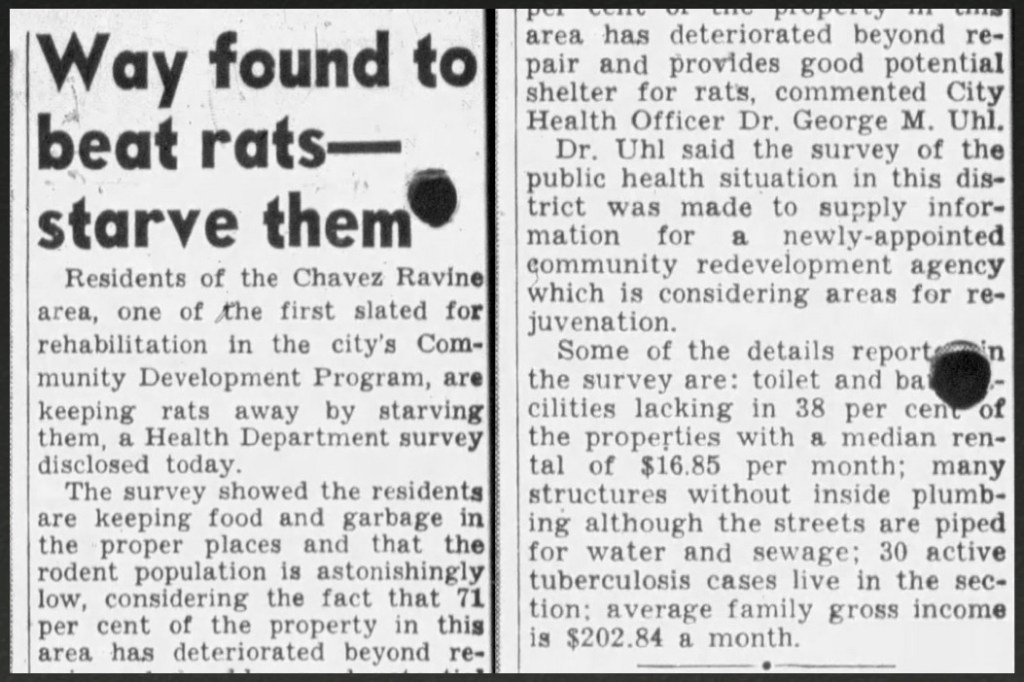

Oh, and as long as we’re on the subject of the vaguely unpalatable—Ravine residents were wining the war against the rats:

And that, dear readers, is a snapshot of life in Chavez Ravine in the 1940s. Join us next time when the 1950s dawn, and Chavez Ravine changes forever…

This is seven-part series. Its component parts being:

Part I: Chavez Ravine and the Mainstream Narrative

The master narrative, as promulgated by the mainstream media; its result, a reparations bill; the good and bad of that bill. Published Friday, May 10.

Part II: What is Chavez Ravine

Its beginnings, development, and evolution to 1950; its history of demolition prospects; and, can you call it Chavez Ravine? Published Sunday, May 12.

Part III: Calm Before the Storm

A snapshot of life in the area in the 1940s. The mythos of small-town life; Normark’s documentary work; a study of the people of Chavez Ravine; churches, markets, bus lines, etc. Published today, Tuesday, May 14.

Part IV: The Rise and Fall of Elysian Park Heights

A history of public housing; Neutra’s Elysian Park Heights project; its proponents and opponents; the area’s demolition; the downfall of public housing, and its relationship to anticommunism; land use after the demolition and nullification of the contract. To be published Thursday, May 16.

Part V: Here Come the Dodgers

About the Dodgers; what constitutes public purpose; an illegal backroom deal?; a stadium is built. To be published Saturday, May 18.

Part VI: The Arechiga Family

The Arechiga family history to 1950; eviction from Malvina Street; eventual removal in May 1959; the multiple Arechiga houses; life after Malvina; the next generation of Arechigas. To be published Monday, May 20.

Part VII: In Summation, plus Odds and Ends

Key takeaways; plus a collection of *other* commonly-held beliefs about Chavez Ravine, conclusively debunked. To be published Wednesday, May 22.

If you have comments or corrections, please don’t hesitate to write me at oldbunkerhill@gmail.com.