The story so far: we introduced our subject in Part I by detailing how Chavez Ravine’s Master Narrative, from which came the Reparations Bill, is equal parts unsupportable claims and outlandish disinformation. Part II made sure you knew Chavez Ravine’s history. Part III provided a snapshot of life in Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop during the 1940s, before it was forever changed. Part IV ran us through the story of the ill-fated Elysian Park Heights project, for which the Housing Authority removed all the residents and demolished the structures. Part V told the tale of how and why the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles.

Today! We have arrived at the most famous story of all. That of the Arechiga Family.

I. The Most Famous Photo of All

On May 8, 1959, after years of court battles and multiple eviction notices, LASD deputies finally removed the Arechigas from the two houses they occupied.

The mere mention of the Arechiga family—just the sight of this one solitary image—is all you need to prove that racist Dodgers AKA the Displacers attacked and violently and illegally evicted hundreds of families from their legal homes in May 1959.

Of course, the actual facts behind the matter are more…nuanced. Claims of racism are just that, claims. Despite being popularly renamed “Displacers,” the Dodgers literally displaced no-one. And, despite what you’re told by the ruling chronicle, of Chavez Ravine’s “many families expelled” the sum total number of families dislodged by deputies was…one. The number of people actually forcibly removed was…one. Oh, and there was nothing illegal done to them.

Yes, to be strictly accurate—again, let me be clear, I do not approve of the taking of people’s property, but a thoughtful discussion requires we begin with legal clarity—the Arechiga family hadn’t owned their home for seven years, paying neither rent nor property tax, and had used the courts to stall multiple evictions over the course of years, until the day finally came when there was no other recourse but to remove them by force.

At which point (we are often told) they became homeless. That is, of course, not true either. They simply moved nearby, into one of the many other houses they owned.

The greater Arechiga tale, when factually observed, is actually not much of a story. However, the Arechiga narrative has garnered enormous weight and influence: they are, in fact, talked about more now than when they hit the limelight in 1959-1960, back when they were front page news of every major newspaper from coast to coast.

Their tale underscores why iconic photos are so important—were it not incredibly easy to use the shot of deputies carrying Aurora Vargas, the story would be no more or less important than a recounting of any other people removed, say, from Bunker Hill (or from the sites of countless other projects in Los Angeles involving eminent domain). Don’t get me wrong: the people removed from Bunker Hill were and remain enormously important, as were/are the people of Chavez Ravine; it’s just that the Arechiga family aren’t more important. Regardless, they have since become the go-to hallmark of the story because they so deftly worked the media, and continue to do so, as we’ll see.

II. The Arechiga Story to 1950

Abrana Cabral was born in Monte Escobedo, a municipality in the southwest portion of Zacatecas, a landlocked state on the Sierra Made mountain range of central Mexico, in 1897. In 1916 Abrana, pregnant, marries one Nicholas Ybarra, and together they cross the Rio Grande into Texas in October of that year. In April 1917 Abrana births daughter Delphina in Morenci, Arizona. Nicholas died of syphilis in August 1918.

Manuel Arechiga, born June 1889, was also from Monte Escobedo. He too had fled Mexico for Arizona; he weds the widow Abrana in 1920. They have daughter Aurora Arechiga in Morenci in June 1921.

Manuel worked at the Phelps Dodge Copper concern, but the cessation of World War One resulted in plummeting copper prices; many smelters were closed and jobs lost. Manuel and Abrana, seeking greener pastures, head west to Los Angeles, in 1922. They settle in the westernmost part of Chavez Ravine, on Malvina at the edge of the Palo Verde Tract. They have a son, Juan, in February 1923; daughter Celia in April 1924; Manuel Jr. in October 1926; and Victoria in November 1929.

III. Their Houses

The famous houses for which they are known are 1767, 1771, and 1801 Malvina (it is from 1771 that Aurora Vargas is famously carried, making it arguably one of the most famous houses in Los Angeles history). These three are the houses it is said the Arechigas built, because they owned them in 1959 (although by 1959, the Arechigas had already demolished 1801 themselves). In all likelihood they built none of the three, but rather purchased them over time.

In the 1930 census the whole family are shown as residing at 1813 Malvina, and they’re in the 1934 phone book at 1813 Malvina. There’s no record of the construction of 1771 in DBS filings; but Arechiga is shown as its owner in 1940.

1767 was built by a man named Jose Rodrigquez in late 1923, though Manuel Arechiga is listed as its owner on Building & Safety permits in 1946.

In 1940 they’re renting a house at 1801 Malvina (the family numbering only seven now, since Manuel Jr. died, age eight, of tuberculosis), and Manuel’s 1942 draft card shows him living at 1801 Malvina. At some point Manuel purchases 1801 after 1940.

Though they own 1771 in 1940, they’re not seen living at 1771 until a 1943 newspaper mention (seen below). In the 1950 Census, Manuel and Abrana live at 1771 with their son Juan, and his wife Nellie and their daughter Helen, along with Victoria. Aurora, Celia and Delphina have since moved on to start their own lives (Aurora lived on Hyde Park Boulevard).

IV. Living their Lives

From the 1920s through to the 1950s, the family lived their lives in Palo Verde—which we might expect to be uneventful—but they made the papers now and then. For example, teenage Victoria Arechiga turned her back on her pet goat, who butted her down the hill, sending her to hospital for X-rays.

Less “human interest story” was the car-crash killing done by Porfidio Vargas, an Arechiga family member.

Jose Ambrosio Barboza Vargas was born in 1897 in Irapuato, Mexico. He, his father and mother, Jose Gregorio and Maria, and five siblings, crossed into Texas in 1907. Ambrosio and Jose Gregorio made their way to Los Angeles and were one of the first families to build in Chavez Ravine, in 1913, as part of Stimson’s settlement program. In 1915 Ambrosio, 18, married Tiburcia Gonzalez, age 16. They had nine children (of whom Porfidio was third born, birthed in March of 1919). Ambrosio became an American citizen in Los Angeles in 1932. Their house was at 1767 Gabriel, a stone’s throw from Malvina.

Porfidio met Aurora Vargas, who lived one block over at 1801 Malvina. They were married in 1938; she was 17.

In June 1941 Porfidio was 22 years old and a member of the Palo Verde gang. He and his gang crashed a party being held in Rose Hill gang territory on Boundary Avenue. A brawl ensued, and Palo Verde gang member Juan C. Flores, of 1738 Gabriel Ave., was stabbed, near fatally. After that, Porfidio got into a game of chicken with a Rose Hills gang member, Ramon Araujo. Neither budged, and the cars crashed head on, at the corner of Boundary and Roberta (which converged, once, before eminent domain came and took out huge swaths of houses for Rose Hill Park). Remarkably, both Vargas and Araujo survived, but both of Araujo’s passengers—Peter Barraras, 16, and Peter Del Gado, 18, were killed. Porfidio Vargas fled the scene, but was arrested the next day.

Vargas and Araujo went before the Municipal Judge for felony negligent homicide, but were set free because gang members threatened all the witnesses.

Porfidio was inducted into the US Army in June 1943, and sent to Europe. In December 1944 he was one of the very first to die in the Battle of the Bulge, which would claim 20,000 American lives in the Ardennes that winter, leaving Aurora a widow.

Another sobering story involves Juan (AKA John) Cabral Arechiga, Manuel and Abrana’s only living son. In December 1942 Juan, 19, gets married to Nellie Tavison, also 19, and have daughter Helen in September 1943.

Then, on March 18th, 1944, Juan Arechiga kidnapped and raped an underage schoolgirl. Juan abducted Mary Louise Fernandez, 17, of 622 North Broadway, a junior at Lincoln High, whom he grabbed on Ord near Broadway as she walked home after school. After abducting her, Arechiga beat her, threatened her if she made noise, and drove her into Chavez Ravine and raped her in the dirt. Fernandez immediately turned him in and it goes to trial, where Juan is found guilty. People will say well, of course they found him guilty, poor people only get some terrible public defender who doesn’t even care about him because the system is broken, etc.

No. His parents Manuel and Abrana hired the famed trial lawyer Rosalind Goodrich Bates, but despite top-tier defense, the jury still found him quite guilty. Juan goes to San Quentin in December 1944, and serves four years for kidnap and rape.

Other than those instances, the Arechigas led a quiet life. Until that fateful day…

V. The 1950s

July 1950, everybody gets the letter saying your days are numbered: we, the City Housing Authority, are coming for your house, which we are taking through condemnation. This includes the Arechiga properties, which stand at 1767, 1771 and 1801 Malvina.

Remuneration was fixed at $10,050 by the Superior Court of California, wherein, for their property, the Superior Court looked at three appraisals of their property, and then picked the appraisal with the highest value.

They are given $10,050 for the three lots, which doesn’t sound like much, but the going rate for a house were you to buy one in Chavez Ravine in 1951, was $2000.

But, you say, that can’t be right! But it is: the average cost of a home in 1950 in Chavez Ravine was $2000. Here, for example, are some random home values from very nearby, via the 1940 Federal Census.

1766 Malvina, $700; 1767 Gabriel, $1500, 1722 Malvina, $1500; 1255 and 1259 Effie, $900 and $1600. Unfortunately, come the 1950 census, the US Department of Commerce Bureau of the Census discontinued providing home valuation. But, let’s say that home values doubled in the decade 1940-1950. That puts us right there with the $2000 average 1950 valuation. Bear in mind, the average cost of a home in 1950 was $7,354 in the United States; that the Chavez homes were only 30% of the national average is completely understandable, given all we know about their general construction, the neighborhood services, etc.

Bear in mind as well, the average value of three homes in Chavez Ravine, at $2k per, $6,000. The $10,050 appraisal on the three Arechiga properties is nearly double the average going price in the area.

If you don’t agree with the amount of money they award you, you file an appeal. The people who filed appeals got more money; many of the Arechiga neighbors did. The Arechiga family, however, for whatever reason, did not feel the need to file an appeal.

A couple years go by, and they never file an appeal, and eventually the appeal window closed in February 1953, and that is that.

Ooops, not yet. Come October 1953, the Arechigas file suit in Superior Court against the Housing Authority. The Housing Authority asked for a writ of possession, which would have dispossessed the family immediately. The Arechiga lawyer, George Gailliard Bauman (attorney, hardcore Republican, and president of the conservative Small Property Owner’s League) blocked the move and obtained a 30-day stay of execution from Superior Court Judge Samuel L. Blake.

That 30-day stay of execution lasted five and a half years.

The Arechiga’s argument was someone told us our property was worth $17,500. You only deposited $10,050 in our account. Give us the extra $7,450, and we’ll pack up everything and go.

Problem is, they had two years to file an appeal, as many neighbors had. The Arechigas didn’t, so, the judgement became final. In court, the judge realized that if people were to sidestep procedure and insist on setting their own price in eminent domain proceedings, nothing—no roads, no schools, no court houses, no public housing—would ever be built. The Arechigas were told sorry.

1953 ends. 1954 goes by. So does 1955, and then 1956. The Arechigas live in the cleared-out Ravine. (Of course I shouldn’t have to repeat this, but no, during this entire time there exists not the slightest inkling of anything related whatsoever to the Dodgers.)

In 1957, the Arechigas, after waiting four years to get evicted, finally get evicted. But I thought they didn’t get evicted until 1959! you say.

The Arechigas didn’t own their house from 1953-1957, while they battled in court. The matter goes to the District Court of Appeal in 1957, and the presiding judge said “when the judgement in the condemnation case became final, they were divested of all interest in the property regardless of the purpose for which it might later be used.”

Now you may not like it, but, fact is, when the State takes your home for eminent domain, you don’t get to keep it. If you think it only happens to poor people of color, consider the hundreds of homes in southwest Pasadena, taken by Caltrans, for the 710 project. That never got built, and those homes aren’t going back to the owners, are they.

Fact is, the Arechiga place on Malvina, was legally not their home. They lived there for years without paying rent or property taxes. The City could have very easily said well this is our home not yours, we’re turning off the water and power, but they didn’t do that, did they.

And at this point, in the spring of 1957, we finally have some mention of the Dodgers! In May the National League owners granted permission for the Dodgers to move to Los Angeles if certain conditions were met.

After the Arechigas lost their court case (again) in 1957, they were served an official eviction notice and on the 21st of August, 1957, deputies showed up with a Writ of Possession and evicted them, and began hauling out their belongings.

Daughter Victoria Angustain (Victoria Arechiga had married Miguel “Mike” Angustain, an employee of the Department of Recreation and Parks) punched and bit officers removing the furniture, but hey—if deputies are such fascists (as we are so often reminded), they’d beat Victoria with truncheons, right? No, instead the Arechigas were granted a two-week stay on the eviction order (Councilman Roybal intervened), so the deputies had to haul all their belongings back into the house, and that two-week stay turned into another two years of squatting.

It was wrong to turn them out, Victoria stated, because (besides wanting their oil rights!) they had no place to go:

Which, you are going to find out, was a big fat lie.

1957 turns to 1958 to 1959, with the Arechigas waiting patiently for the next eviction order. (They had had their final appeal denied in April 1958—read the judgement here.)

The subsequent order to vacate comes on March 9, 1959: they are served a 30-day eviction notice: you are going to be out on April 10, 1959, no ifs ands or buts. Abrana looks at the notice on April 10th:

April 10 was the day the Arechigas were supposed to be out, but they stalled further, and were granted another 30-day-stay.

May 8th, therefore, became, after nearly a decade of stalling, the day they were supposed to be out (you will hear “the City was mean and evil and evicted them on Mother’s Day weekend!” but for accuracy’s sake, their eviction occurring on Mother’s Day weekend…was entirely the work of the Arechigas and their lawyer).

VI. The Big Day

Friday, May 8th, 1959: at 11:30 in the morning, eight male and three female LASD deputies arrived to enforce the March 11 Superior Court Writ; they were led by Capt. Joe Brady. They were joined by fifteen cars full of television reporters and the press. Three moving vans had already arrived. It was the deputies’ intent to take possession of 1771 Malvina (home of Manuel and Abrana) and 1767 Malvina (home of Victoria and Miguel Angustain). 1801 Malvina had already been demolished by the Arechigas, for reasons unknown. (Alice Martin, 1456 Davis; Sally Ramirez, 1850 Reposa; and Glenn Walters, of 1853 Reposa, also left that day, without incident, although Walters was detained for obstruction during the Arechiga dust-up. Martin had bought back her house from the City, for $2,500, with the proviso that it be moved, but was then found to be not structurally sound enough to be moved.)

Deputies entered, then engaged in discussion with Victoria and Abrana about leaving (Manuel remained outside; Aurora wasn’t there). Workmen began to remove personal items into moving vans.

Aurora Vargas arrived on the scene. She ran past the deputies, and announced to the reporters, they’ll have to carry me out! And with that she ran up into the house.

Remember, the only people that lived in the 450sf house were Manuel and Abrana. Aurora lived miles away, and only showed up to be on TV: the deputies complied with Aurora’s demand, and it has become one of the most famous images in Los Angeles history—

Aurora kicked the officers and punched them, and was arrested for battery. (Though Victoria Angustain left peacefully, she later fought and struggled with police, but they let it go.) Released on bail, Aurora’s alleged battery went to trial: a jury of ten women and two men found her unanimously guilty, three counts of battery and one for obstruction, which was easy to do since there was so much film of her kicking and punching officers.

The cameras rolled and rolled—

—it was the perfect media circus. It made the news coast-to-coast. Of course, as is their way, the media “helped” a little; here for example is the aforementioned Alice Martin and her roommate, Ruth Rayford, of 1456 Davis:

At the end of the day, eight years after the Arechigas lost their house, they finally lost their house. Their belongings were loaded into three moving vans—

And the houses were demolished.

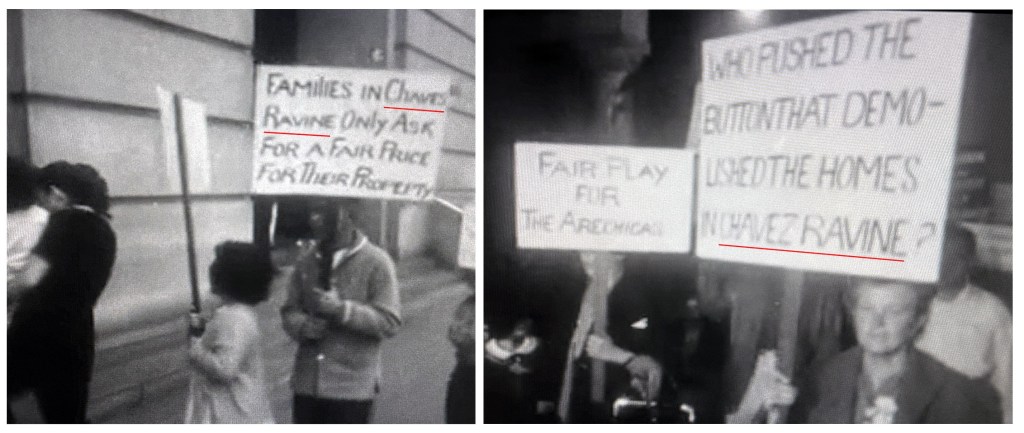

But the Arechigas did not depart. They were prepared with their tents and cookware and set up camp. The removal and demolition was a huge national story, covered coast to coast, and Los Angeles was a national, in fact, international embarrassment.

The City Council granted them the opportunity to speak at a public hearing, which they did on May 11.

300 people packed council chambers, loudly denouncing the thugs who made innocent people homeless. The Arechigas agreed: they had been set upon without warning, impoverished, and now had nowhere to go. The newspapers reported that they were homeless:

Homeless, they lived in a tent:

Then, they lived in a donated trailer:

Of course, they weren’t homeless. Not by a long shot.

VII. The Arechiga Homes

That is correct: despite what you’re constantly told, they were not made homeless. Not even remotely so. And we’ll set aside the fact that not one person in Chavez Ravine was made homeless, not one, because the Housing Authority worked diligently to relocate and find new homes for every single Ravine resident, as per the law. No, what made the Arechiga family interesting and unique is that…they could have just gone to one of their many, many other homes.

The Arechigas, however, just didn’t feel like going to any of the many houses owned by them, or houses owned by their son, or the homes owned by their daughters; between the folks and John and Aurora and Victoria, ten houses, eleven if you count the one daughter Celia owed and lived in out in Santa Fe Springs. Rather, they liked living in donated housing in Chavez Ravine, eating donated food, yelling at councilmembers, and getting in the papers.

The day after the big Council hearing, May 12, 1959, somebody thought to look at the tax rolls, and well look at that, they own eleven homes.

Victoria (who owned three of the eleven) said, basically, “well we never denied owning eleven houses, it’s your fault you never asked us if we did”—

You will be told “they didn’t REALLY own all those homes!” Here is that claim, for example, in the “Battle of Chavez Ravine” Wikipedia page—

Sigh. I hate to have to do this, but because you’re being fed b.s., I’m now forced to detail all the homes they owned.

The home of Manuel and Abrana Arechiga:

Yes, they and they alone owned it outright. It is located at 3649 Ramboz Drive in City Terrace, and was brand new when Manuel and Abrana bought it in 1956.

…and by 1959 they’d already paid off more than half the mortgage (they had purchased it for $8,500 in 1956, and in May 1959 only owed $3,700 on the mortgage). At the time of the Malvina eviction, they were renting it to their cousin, Estella Moldanado. It was to this house Manuel and Abrana moved in 1959, immediately after leaving their “homeless tent” in Chavez Ravine. Here they are, in the 1960 Los Angeles telephone directory:

And this is the OTHER home legally purchased and owned by Manuel and Abrana Arechiga:

This house is at 2410 Glover Place. Three bedroom, built in 1925. They had their 42-year-old daughter Delphina Hernandez (Abrana’s daughter from Nicholas Ybarra) living in it.

Daughter Victoria was also not made homeless, she and her husband Miguel Angustain Jr. owned property at 1430-32 Allison Avenue, a stone’s throw from Chavez Ravine.

Strictly speaking this is THREE houses, since there are three separate standalone structures on the lot. Two houses in front running down the sloped site, this being the house in back:

In fact here’s a shot of the family hauling the furniture from Chavez Ravine up to their house:

What of daughter Aurora Vargas, the one famously carried by force from “her” home at 1771 Malvina? She owned both these homes:

These are two houses at 659 and 657 Simmons Avenue, for which Aurora Vargas had paid $8,500 and $5,600, respectively.

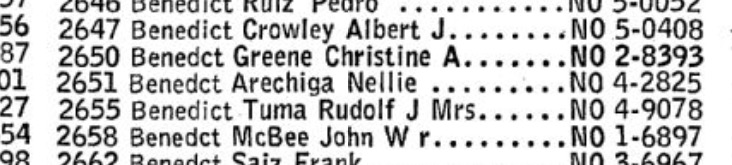

In 1959 son Juan Arechiga owned a house at 2651 Benedict Street — classic Spanish Revival, built in 1929 — which he had purchased in the spring of 1955. You will be told that it was being taken by eminent domain, and Juan was forcefully made to sell his home, in order to build a stretch of the Golden State Freeway (a story repeated in Eric Nusbaum’s book Stealing Home, for example). But that’s not true: Juan sells it himself, in 1965, to an outfit called Quality Bilt Homes. QBH tear it down, and erect an apartment building on the site (which opened in 1967, and still stands). Juan’s house on Benedict:

Juan Arechiga also owned another house. It was this two-unit at Ewing Street & Echo Park Avenue:

You will be told that this house is important because it’s where the Arechiga family “fled” after the Malvina demolition. But as is the case with so much Chavez Lore, you are being lied to. Juan (who did not live in Chavez Ravine) bought this house in March 1959. In May of that year his parents were evicted from Malvina, and they moved to their house on Ramboz. NO-ONE removed from Chavez Ravine ever lived in this house; this house has no relationship with or to the Arechiga/Palo Verde tale. Juan owns it for all of five years, and sells it to a man named Maurice Owen Eubanks in March 1964. (FYI, 1553 Ewing St./2004 Echo Park Ave., AKA the “Queen of Elysian Heights” made the news recently, and I’ll cover that in the next installment, Part VII.)

And lastly, here’s the home of daughter Celia, which sort of counts but sort of doesn’t. Like Delphina, Celia didn’t muck about with the Chavez Ravine doings much.

Also, it was out at 9112 Arlee Ave., Santa Fe Springs, seventeen miles southeast of Chavez Ravine, so it doesn’t really fall under the umbrella of the Los Angeles Arechigas…but still.

Just to give you an ironclad understanding of the eviction-involved Arechigas:

Manuel and Abrana live the rest of their lives in their house on Ramboz; they pass in 1971 and 1972, respectively. Juan and Nellie pass in 2010 and 2018; Aurora in 2006.

Juan and Nellie’s daughter Jeannie, born in 1955, gives birth to Melissa, in 1975. And with that, comes a whole new era of Arechigas vis-à-vis Chavez Ravine.

VIII. Arechigas: The Next Generation

Manuel and Abrana’s great-granddaughter Melissa Arechiga takes on the Chavez Ravine mantle in 2017 when she begins “Buried Under the Blue,” her activist group for reparations to descendants of residents. BUtB get their 501(c)3 in July 2019. In May 2022 she wrote this petition which directly led to the Reparations Bill.

It’s an interesting petition. If you’ve read this post, and the preceding five, you’ll see that BUtB’s assertions are…creative, so much so, I feel no need to address them point-by-point.

Couple things I will point out, though: first, it’s curious to see that paragraph five, concerning Judge Praeger, is a cut-and-paste (with a sentence added at the end) from this pamphlet. Melissa Arechiga snatched the paragraph from a pamphlet published by the Small Property Owners League of Los Angeles, who were right-leaning conservatives, which is rather ironic. Ultimately, of course, Praeger’s judgement is a minor footnote in the greater tale, since it was immediately and unanimously overruled by the State Supreme Court and the Chief Justice.

Secondly, what’s important to note is the meat of the matter, their demands:

As I mentioned in the very first post of this series, historical monuments and community centers, awesome (and I’ll be interested to see how HACLA words their apology). The fundamental essence of Arechiga’s demands lays, of course, in a demand for reparations.

Now, were I a cynical man, I might raise an eyebrow. After all, a demand for money was the entirety of the Arechiga kerfuffle in the first place.

And now, the same family wants more money…again.

A friend of mine likened this to a grift, which I thought was a bit strong; it’s more a strong-arm guilting, I said. He said if BUtB had actual truth and facts, it would be a guilting; but without those, it’s just a con. I’ll leave it for you folks to decide that.

Here’s what may be the most important point. Buried Under the Blue is run by Melissa and her mother Jeannie Arechiga; the acorn that grew this oak is the oft-repeated assertion that Jeannie, three-and-a-half years old, lost her home that fateful day in May 1959. That is mentioned in their BUtB bio, and is therefore repeated in the mainstream press. But it’s baloney. Jeannie didn’t live in Chavez Ravine, and never lived in Chavez Ravine. Jeannie lived with her family in their house on Benedict (pictured above), about three miles northwest.

So when you read the BUtB bio about how Jeannie’s experience at the May 1959 eviction “continues to affect her mental health and well being” always remember: her parents took a 3½-year-old from her home, drove her to where there was sure to be commotion, and placed her in the way of deputies performing their duties, because there were television cameras there.

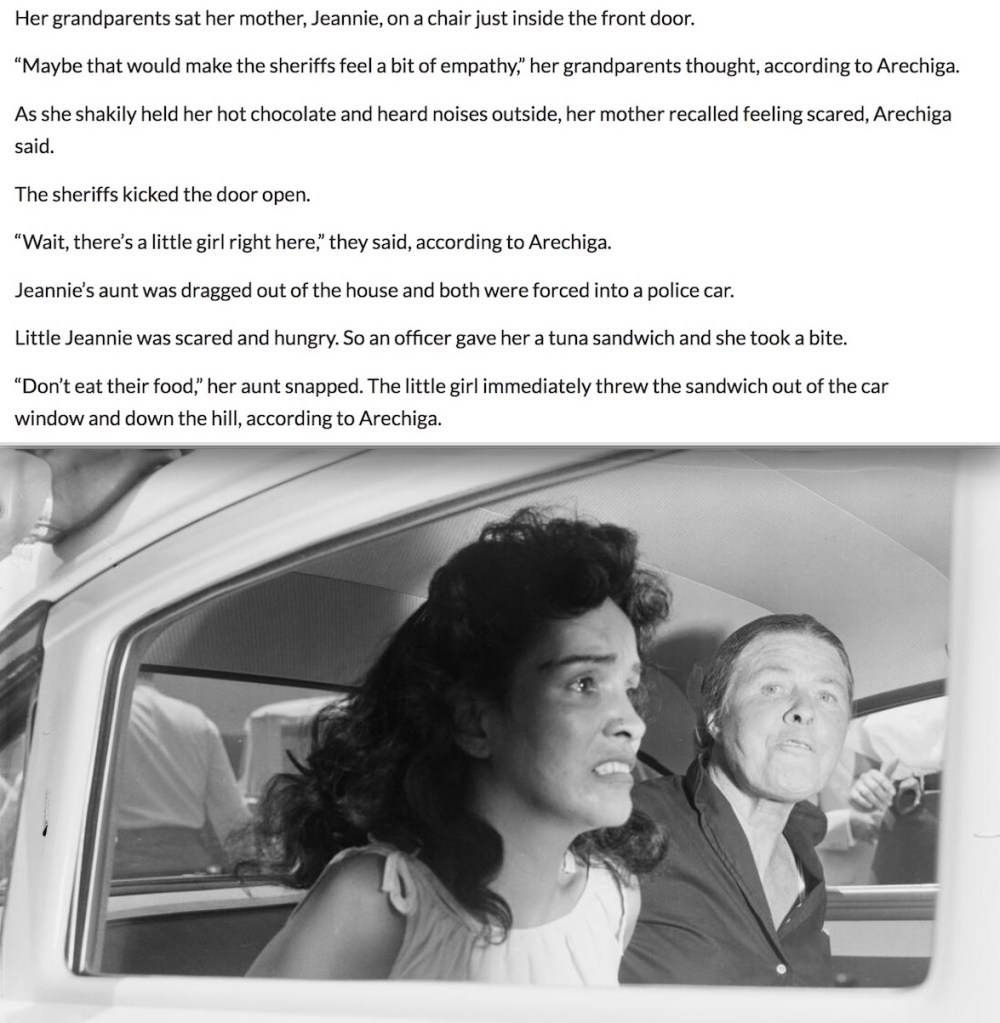

As long as we’re on the subject of BUtB provider-of-origin-story and co-founder Jeannie Arechiga, let’s look at the story that 3½-year-old Jeannie was tossed into the back of a police car next to her aunt Aurora, famously standing up to The Man by tossing their sandwich out the window—

—which is of course a total fabrication. The only person put into the back of the police car with Aurora Vargas was Glenn Walters, who was detained for obstruction. There was a ton of media there that day, and if cops were throwing three-year-old-girls into the back of police cars, that would be the image every media outlet in the world would now lead with instead of the “Aurora Being Carried Out” shot.

*****

In any event, Buried Under the Blue lobbied our elected representatives, and got their demand for reparations sent to Sacramento:

BUtB does much of its outreach on social media; for example, it has 17,000 followers on Instagram, and 23,000 likes on its TikTok. Here is Melissa Arechiga, the new face of Chavez Ravine, with a typical Instagram post:

And that is the tale of the Arechigas! Come back in a couple days when we wrap up our whole tale in Part VII, a breakdown of the main myths about Chavez Ravine. See you there!

**************

This is seven-part series. Its component parts being:

Part I: Chavez Ravine and the Mainstream Narrative

The master narrative, as promulgated by the mainstream media; its result, a reparations bill; the good and bad of that bill. Published Friday, May 10.

Part II: What is Chavez Ravine

Its beginnings, development, and evolution to 1950; its history of demolition prospects; and, can you call it Chavez Ravine? Published Sunday, May 12.

Part III: Calm Before the Storm

A snapshot of life in the area in the 1940s. The mythos of small-town life; Normark’s documentary work; a study of the people of Chavez Ravine; churches, markets, bus lines, etc. Published Tuesday, May 14.

Part IV: The Rise and Fall of Elysian Park Heights

A history of public housing; Neutra’s Elysian Park Heights project; its proponents and opponents; the area’s demolition; the downfall of public housing, and its relationship to anticommunism; land use after the demolition and nullification of the contract. Published Thursday, May 16.

About the Dodgers; what constitutes public purpose; an illegal backroom deal? Published Monday, May 20.

Part VI: The Arechiga Family

The Arechiga family history to 1950; eviction from Malvina Street; eventual removal in May 1959; the multiple Arechiga houses; life after Malvina; the next generation of Arechigas. Published today, Thursday, May 23.

Part VII: In Summation, plus Odds and Ends

Key takeaways; plus a collection of *other* commonly-held beliefs about Chavez Ravine, conclusively debunked. To be published Monday, May 27.

If you have comments or corrections, please don’t hesitate to write me at oldbunkerhill@gmail.com.