Welcome back! The story so far:

Last time, in our introductory Part I, I pointed out that the whole “Chavez Ravine was destroyed by right-wing real estate developers who illegally evicted everyone because they hated Mexicans and violently displaced them and gave them no money for the homes they had been in for generations in a dirty backroom deal so that the Dodgers could build a ballpark and now my grandmother’s house is under third base” is a fantasy—a beloved fantasy—but a fantasy nonetheless. It’s one I’ve heard in various permutations for years; before there was social media, I used to hear it at parties and in barrooms.

And each time, I was told (augmented by the teller’s self-satisfied nod) this was the hidden history. The story no-one knows because it’s the history that doesn’t get taught, it’s the history that’s suppressed. Because all we’re taught in school is how great those greedy colonizers were!

Ok boomer. Maybe your school taught the wonders of the greedy colonizers in, like, 1963, but I went to public school in the 1980s and even then we were already being hit over the head with the Howard Zinn reworking of history.

Consider the fact that the best-selling historian of Los Angeles is Mike Davis, a Marxist who goes on about how horrible Los Angeles is…and the best-selling historian of the United States in general, of all time and by enormous margin, is Howard Zinn, an ideologue who also peddles nonsense, and who sold two and a half million copies of his famously fact-challenged book.

Point being, it’s time to tell the actual history that doesn’t get taught…

Today’s episode: we begin at the beginning and ask, what is this Chavez Ravine of which you speak, anyway?

I. Spanish Colonization, to the Mexican Revolution of 1910

We’ll start way back. So it’s 1542, and the Spaniards explore the coast as far north as Santa Barbara, but then didn’t bother actually settling the land for another 200 years. In 1769 they began the system of colonization, establishing three presidios and twenty-one missions up the coast. In 1777 an independent civil pueblo was established in San Jose, and down in Southern California they followed suit, when in 1781 the Spanish government said okey-doke, send some pobladores, let’s establish El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciúncula (though some argue its original name was El Pueblo de la Reyna de los Angeles).

The government of Alta California, 2000 miles south, didn’t care much about the new pueblo and let it alone. But then the citizens down there in the Mexico colony of New Spain, inspired by the American Revolution fifty years previous, staged a bloody revolution that claimed half a million lives, resulting in an independent Mexico. One minor difference from our revolution: Mexico established a monarchy and crowned an emperor in 1822, though Agustín I was executed by the military in pretty short order. In any event, California was now under Mexican rule.

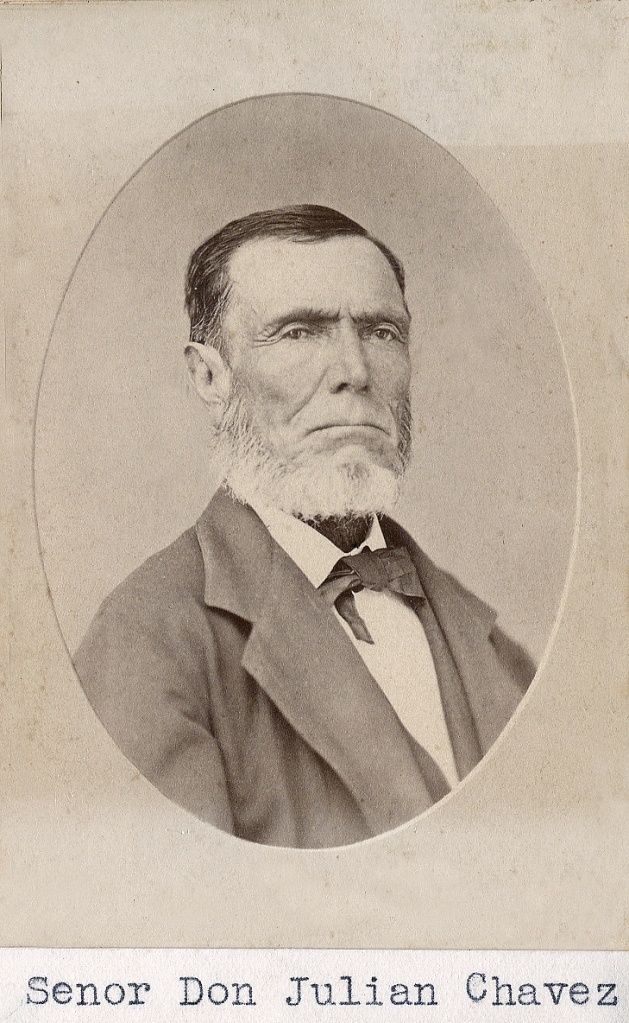

Mexico famously dismantled the mission system of Alta California and began handing out land grants for ranchos, beginning in 1834. It was during this time that a man named Julián Antonio Chávez traveled to Alta California from the east.

Chávez arrived in Los Angeles, got involved in local politics, and in 1838 became the town’s assistant mayor (suplente alcalde), and served as a judge on the Court of Sessions, mediating water and cattle disputes.

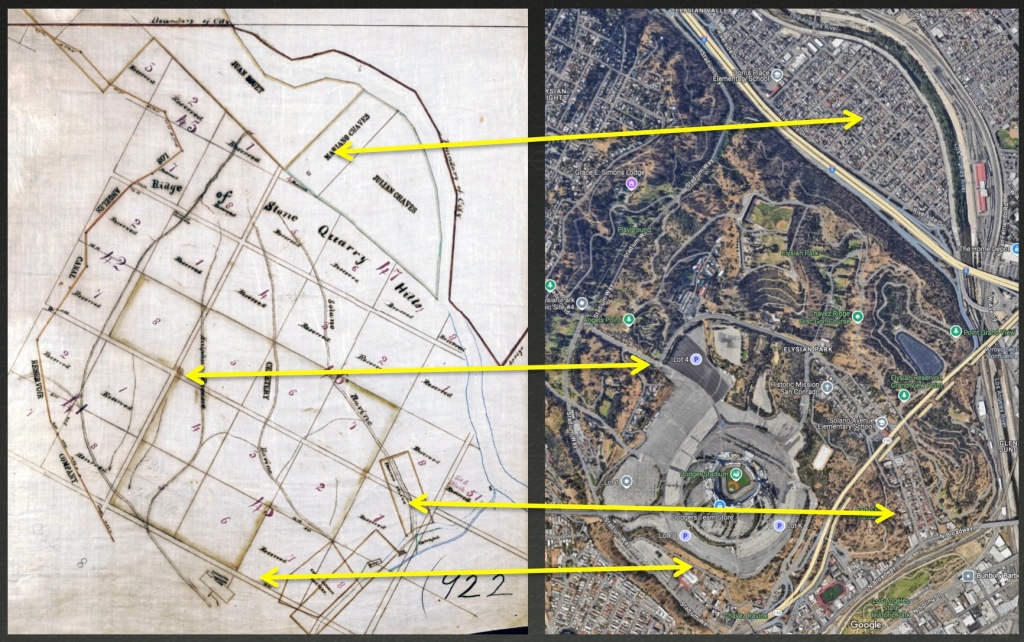

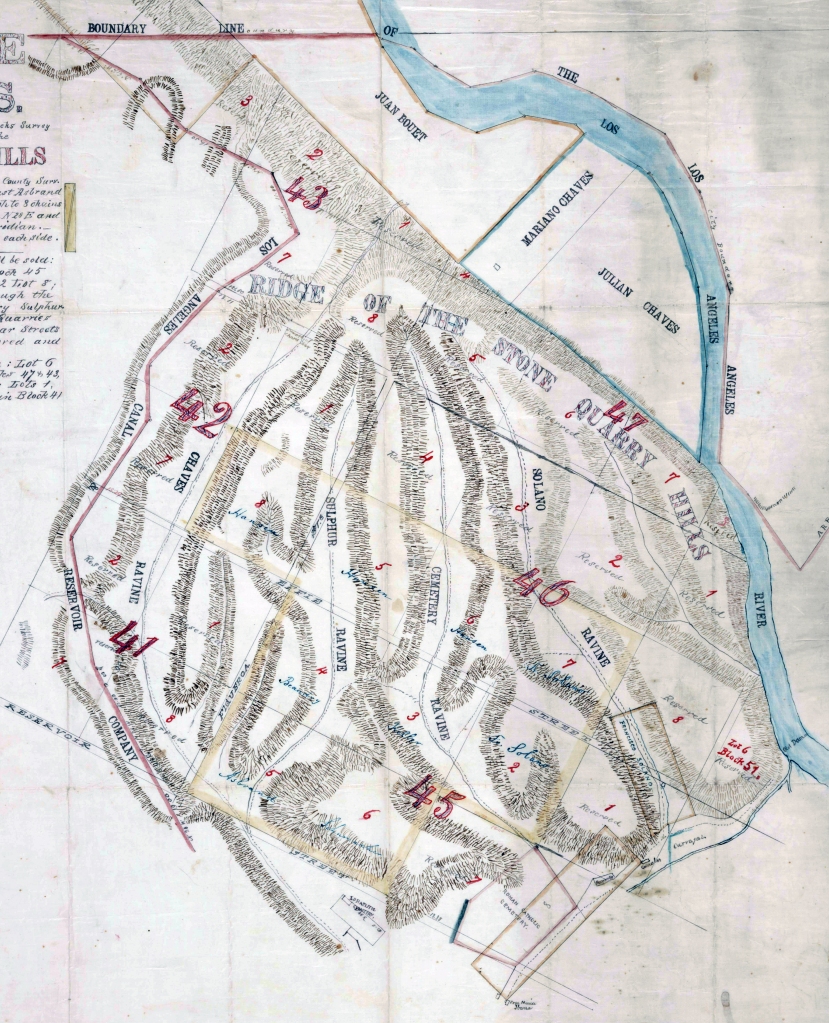

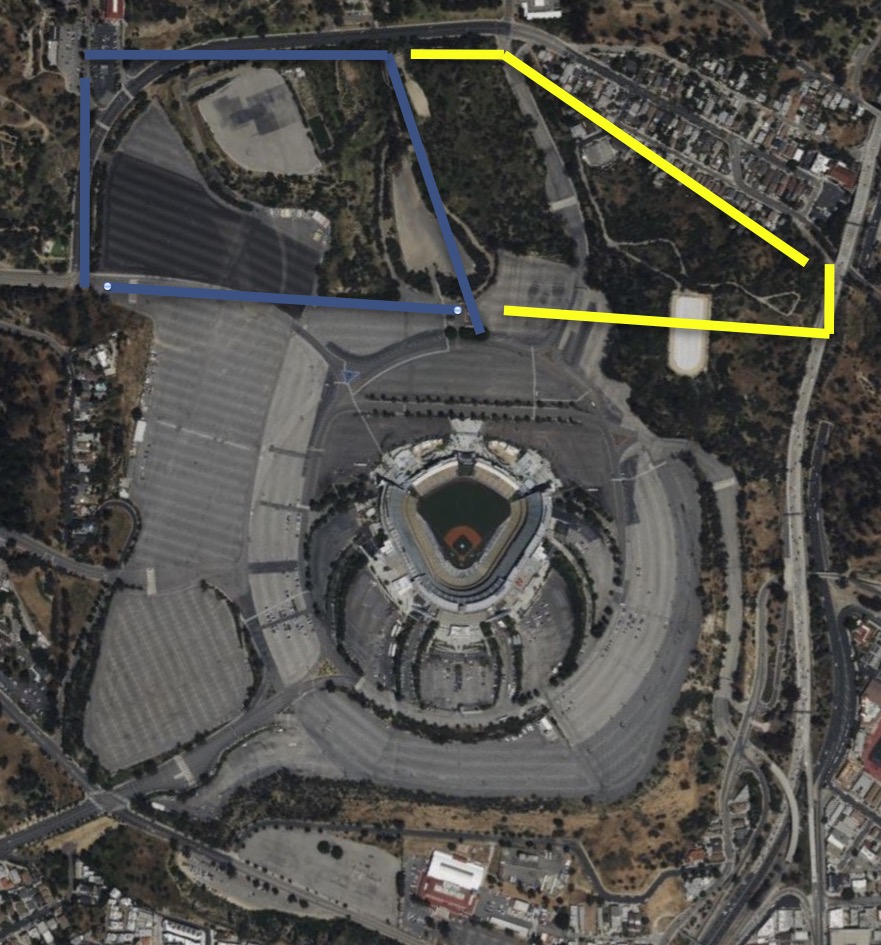

California was under the Mexican flag for 25 years, until a war began in May 1846, ending when US troops captured Mexico City in September 1847. In November 1847, after the de facto end of the Mexican-American war, Julian Chavez purchased some land, 81.75 acres, from a man named Estefan Quintano. Julian’s brother Mariano purchased some adjacent land. This map, ca. 1865, gives you an idea of the layout of things:

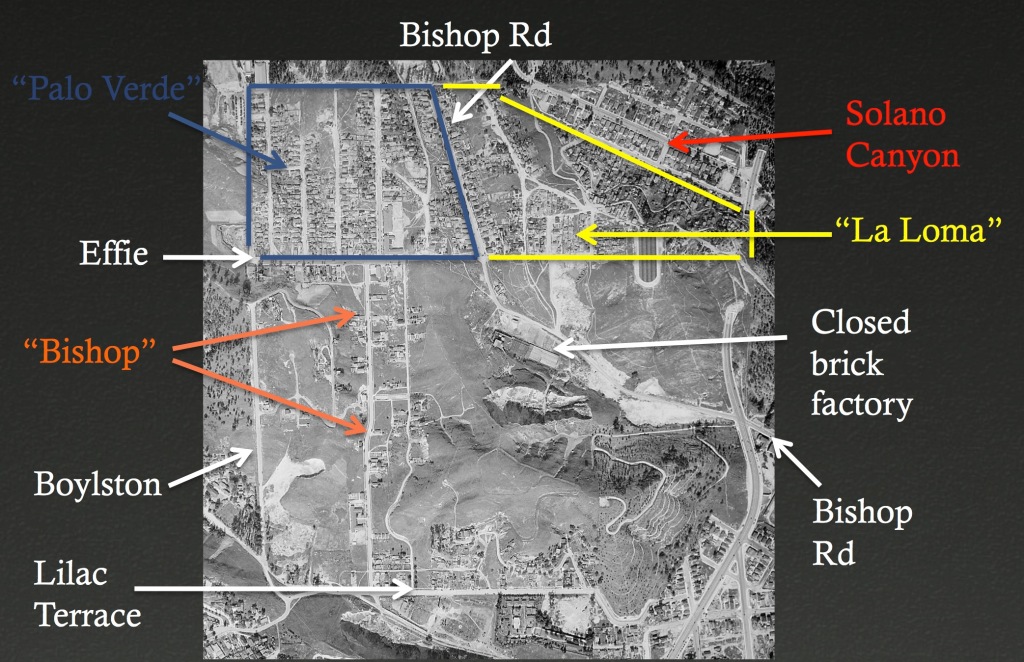

What’s what: top, the lands of Juan Bouet, Mariano Chaves, and Julian Chaves (so is spelled on this map), now thickly populated with development between the river and the Golden State Fwy. Below, an arrow shows what would become the corner of Effie and Boylston; the most developed part of Chavez Ravine, the contiguous neighborhoods of Palo Verde and La Loma, were to the north of Effie, in the two blocks 5 and 6, and part of 7. Third arrow, the Solano Tract, bordered by Casanova Street and Solano Avenue. Bottom arrow shows the position of Lilac Terrace.

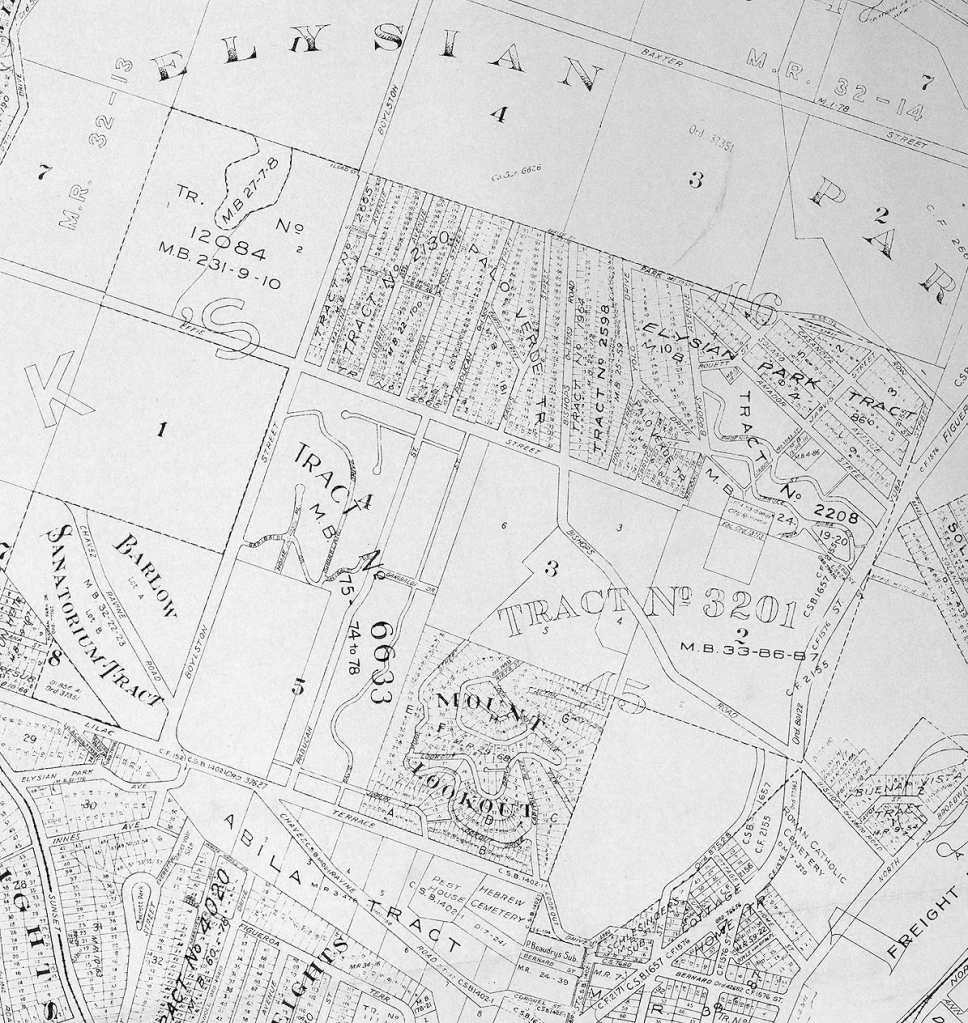

Above, similar map, from 1868. Note the Hebrew Cemetery at bottom, beneath lots 6 and 7 of Block 45, and the Roman Catholic Cemetery adjacent lot 7 (both would disappear long before Palo Verde and La Loma are established; the Hebrew Benevolent Society removed their dead to Home of Peace in Whittier by 1910, and the Roman Catholics disinterred to New Calvary). Again, above Effie, note lots 5, 6 and 7 of Block 46. That’s where Palo Verde and La Loma will develop.

Above, 1884. Note the upper area is no longer called the Stone Quarry Hills; it had been set aside for Elysian Park, dedicated in 1886.

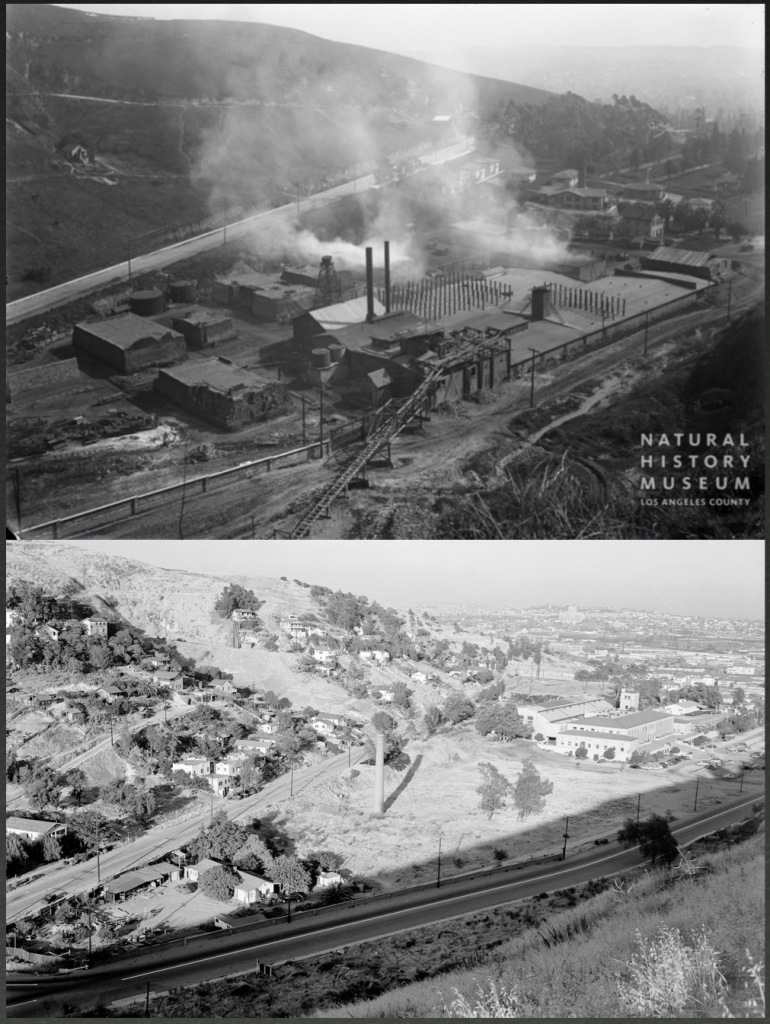

Now remember, the area was once known as the Stone Quarry Hills (sometimes Rock Quarry Hills). Prior to the 1850s the whole city was built of adobe, but the newly-minted American citizens decided to start building in stone and brick. Locals go looking for clay and stone and this area is geologically fortuitous. It’s also outside the boundary of the city, and so a number of brick foundries sprouted up among the ravines (the first brick building in Los Angeles is built 1853). This is the perfect place for brick kilns because kilns are dirty dusty factories, but also, foundries require dynamite blasting of hillsides to get at earthen resources. (Note Block 3 of Lot 46, owned by Keller; that becomes site of LA’s largest brick factory.)

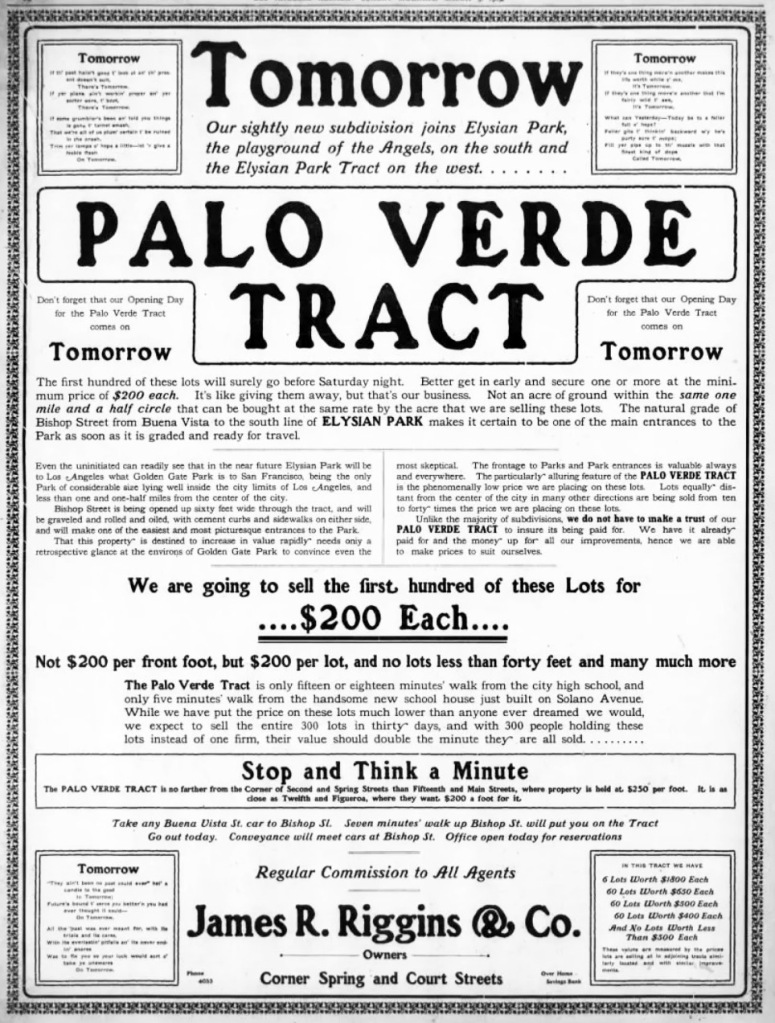

Despite being an area known for its filthy factories and frequent dynamite blasting, in 1905 a man named James Richard Riggins gets the idea to subdivide:

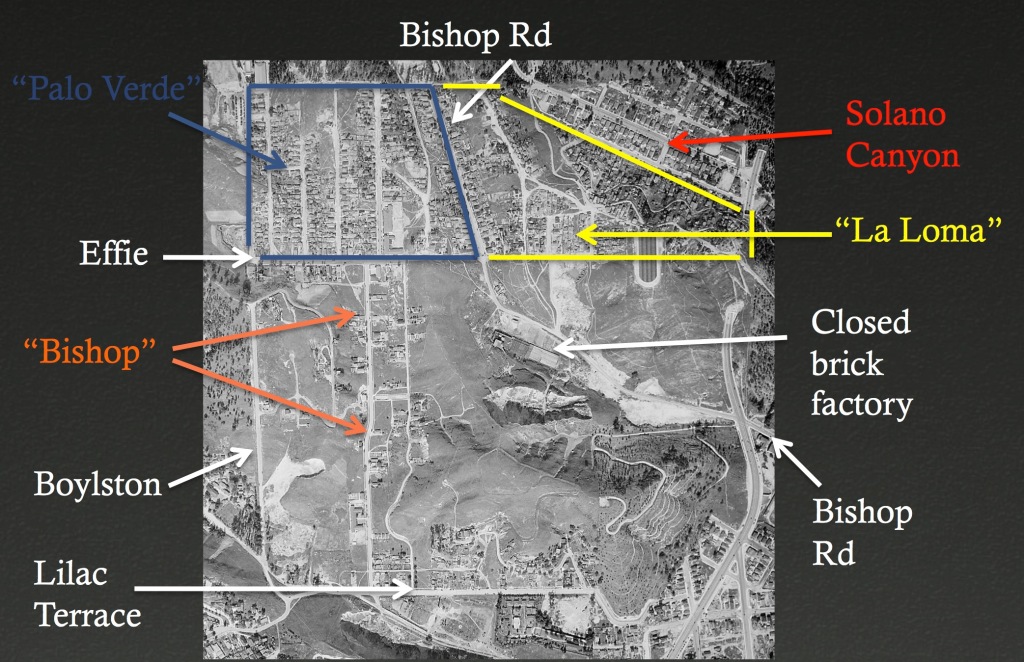

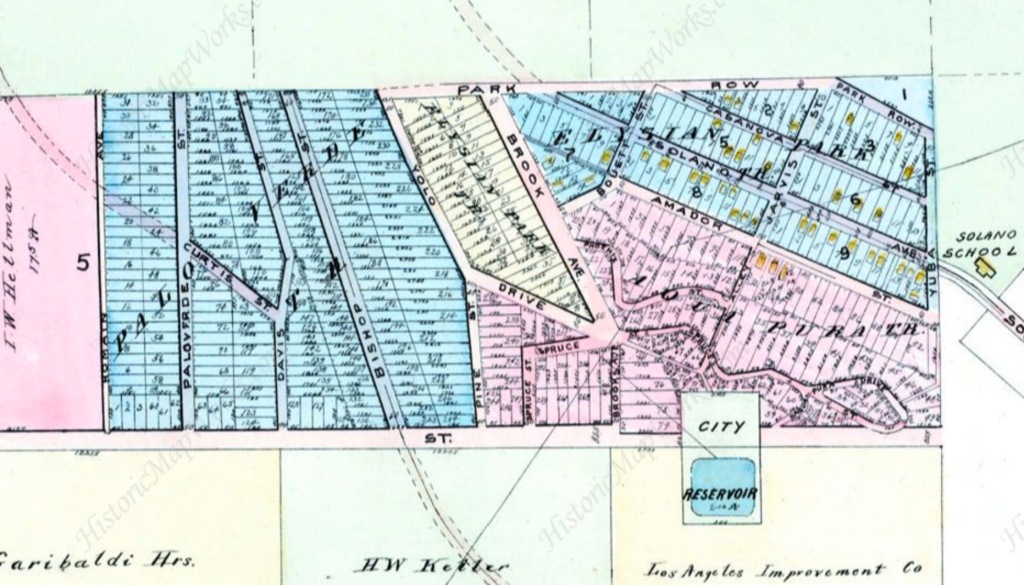

Here we are in 1910: the Palo Verde Tract laid out, at left.

Still no folks in the Palo Verde tract, or the tracts to the east that would become years later known as “La Loma.” The yellow squares at upper right are structures in Solano Canyon, which remain extant.

II. Chavez Ravine is Settled

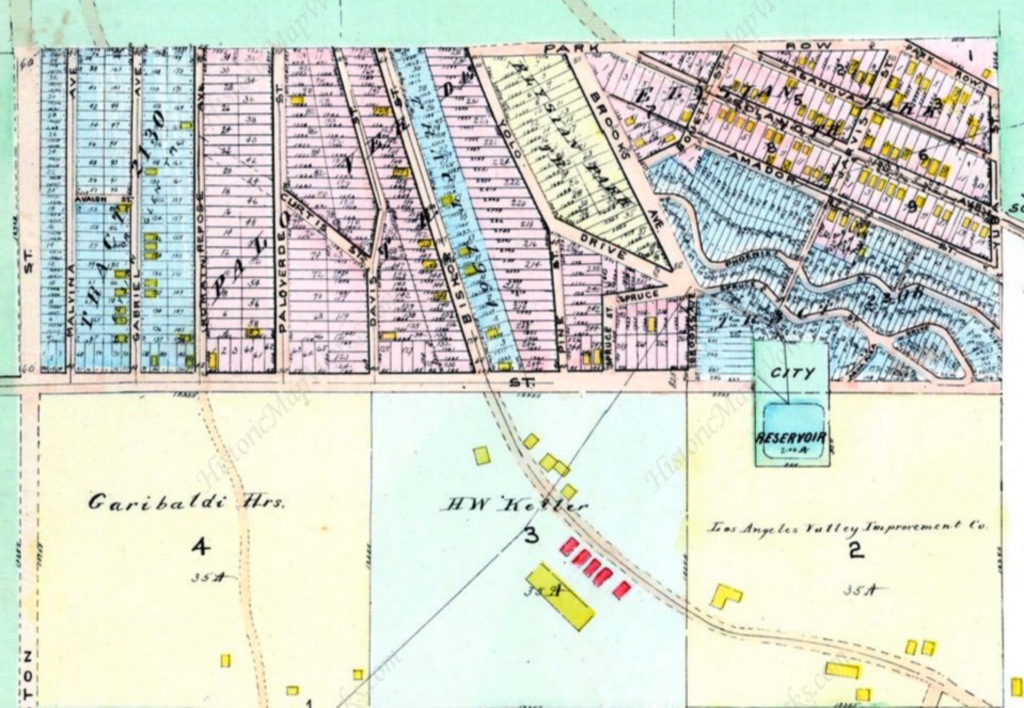

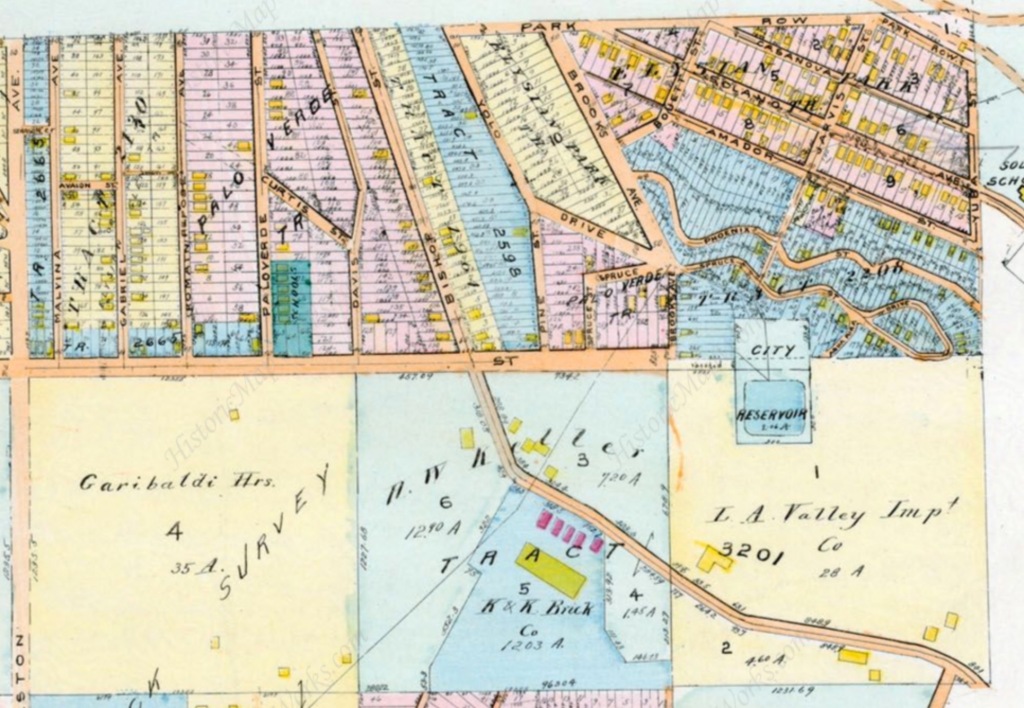

Above, now it’s 1914. A new tract to the west of Palo Verde, Tract 2130, has been developed. 23 structures have popped in what would become the Palo Verde neighborhood, bordered by Boylston, Effie and Bishop. A handful of structures have been built east of Bishop, in the area that will someday be referred to by residents as La Loma. Beneath Effie, Keller’s brick factory and attendant industrial structures.

1921: The Palo Verde area is up to 64 structures now, including the school buildings at Palo Verde & Effie (which would be replaced by a large single structure in 1924; Palo Verde Street would be renamed Paducah). La Loma has enlarged to 24 structures.

What accounts for the increase in the number of structures, from none in 1910 to nearly 100 in 1921? That is largely due to this man, Marshall Stimson.

Stimson was an attorney and a bigwig in Republican politics (at the time of his involvement with Chavez Ravine, he was Chairman of the Los Angeles Republican League, later head of the Republican State Central Committee, our delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1912, and helped put Herbert Hoover in the White House). Stimson bought blocks 42 and 46 and began to market the homesites in lots 4 and 5 to poor Mexicans, because there were suddenly so many of them.

Why were there suddenly so many impoverished Mexican nationals streaming over the border? In 1910 Mexico had another revolution, resulting in the 1911 overthrow of President Porfirio Diaz. By 1913 the revolution—the famous one with Pancho Villa and Zapata—had claimed the lives of more than a million noncombatants. Not military deaths (of which there were about 1.5 million) but 1.1 million Mexican civilians were slaughtered, resulting in a flood of refugees streaming over the U.S. border, escaping Mexico’s murder and starvation, not to mention a deadly smallpox epidemic.

Stimson began selling homesites but even the starving Mexicans escaping war wouldn’t live so close to the brick foundries. People will tell you “he moved 250 families into Chavez Ravine in 1913,” but in reality, the number was less than 100; moreover, Stimson’s intention was to flip homesites to make money, and did so (he developed Watts in much the same way). There’s no evidence of his moving 250 families (not sure why people say he moved 250 families, when he himself said the number was 200), save for him saying he did so, in a statement made 40 years after the fact when he was 75 years old (reminds me of John Rechy, who was 75 when he came up with the Cooper Donuts story, an event that had supposedly happened 45 years previous…and which turned out to be a fabulation).

III. Brickyard Closure and Territorial Expansion

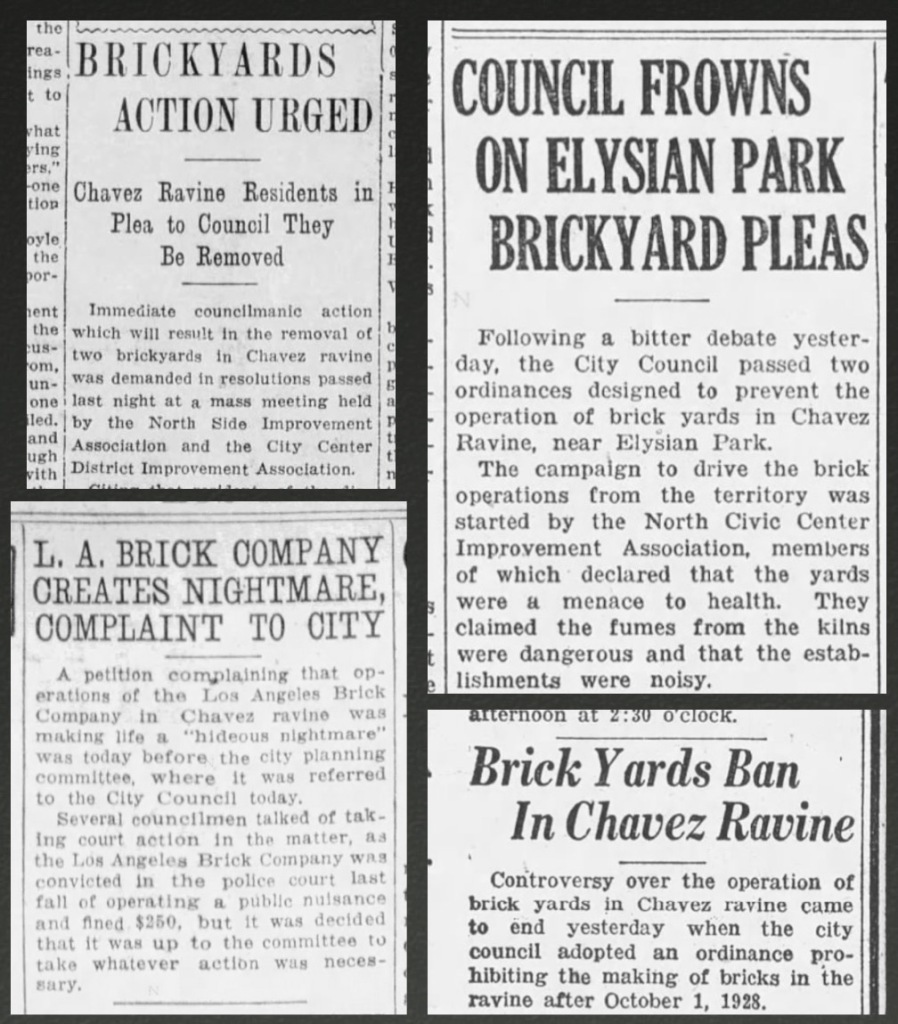

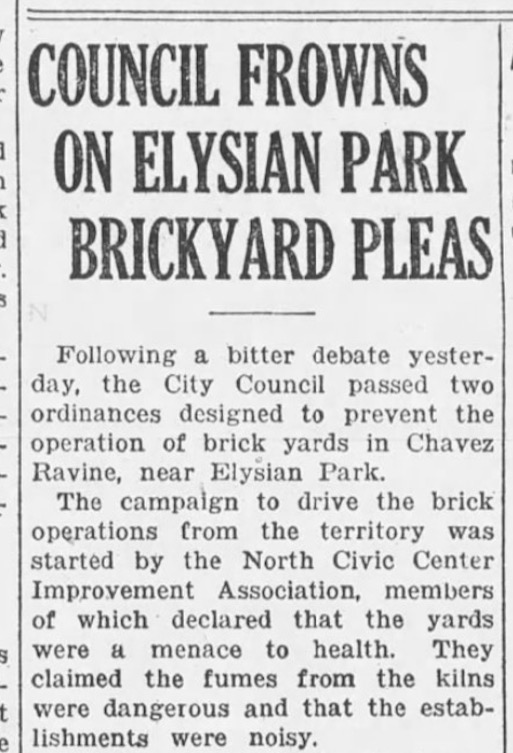

The large influx into Chavez Ravine was largely due to the October 1926 closure of the brick works, which took effect in October 1928.

Above, a closeup from the 1921 Baist Real Estate Atlas page I featured above. Note that at upper left, Palo Verde Elementary is a stone’s throw (or in this case, a brick’s throw) from the C. J.. Kubach/H. W. Keller K&K Brick Company at 1500 West Bishop Road, which covered forty acres, employed fifty men, and produced 80,000 bricks a day. Another massive brick yard—Los Angeles Brick Company, established 1886—was a bit further south at 1000 Chavez Ravine Road, and was similarly forced out of business.

People will tell you that the yards were closed because the “residents of Chavez Ravine banded together and fought the brickworks.” That is not true. The brickworks were shut down by the North Civic Center Improvement Association, who met at the Alpine Street School, 930 Alpine Street. Had efforts been centered in Chavez Ravine they would have met at the Palo Verde primary school. (Moreover, the NCCIA was headed by George Strong, who lived on White Knoll, south of Lilac Terrace; it spearheaded other efforts in the area, like installing a traffic signal at Broadway and Sunset.)

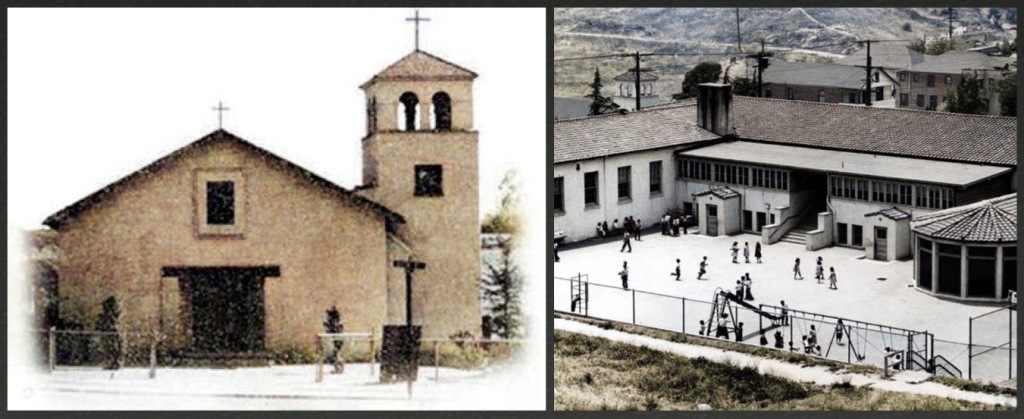

The 1920s had been a time of expansion and settlement; the mid-20s saw the addition of churches and schools. The Palo Verde School at 1029 Effie was built in 1923 and designed by Pierpont & Davis in Institutional Spanish Colonial; two years later saw the erection of another primary school at 1345 Paducah, designed by Winchton Leamon Risley. Also, the Reverend Benjamin Harold Pearson built a Methodist mission at 1205 Effie in 1923. The Los Angeles Diocese built the El Santo Niño Roman Catholic church at 1034 Effie in the summer of 1925; its architect was none other than Albert C Martin, who produced a modified, simple expression of Mission Revival.

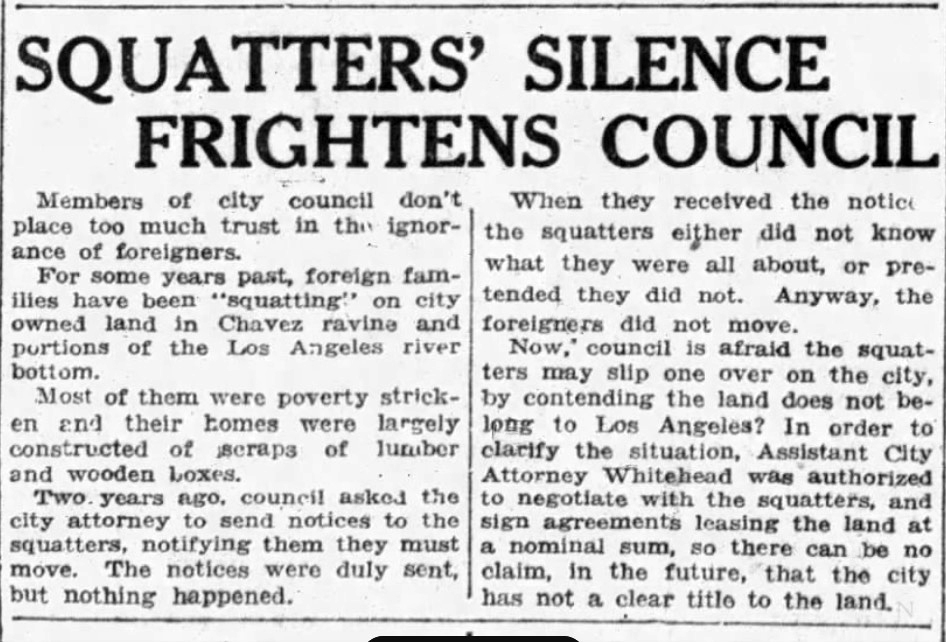

By the mid-1920s Chavez Ravine had taken on a number of squatters, who built without permits or purchasing land (which would account for why so many structures were not tied in to the municipal waste system). It will be interesting to see how this shakes out when forthcoming reparations-themed land claims are examined critically:

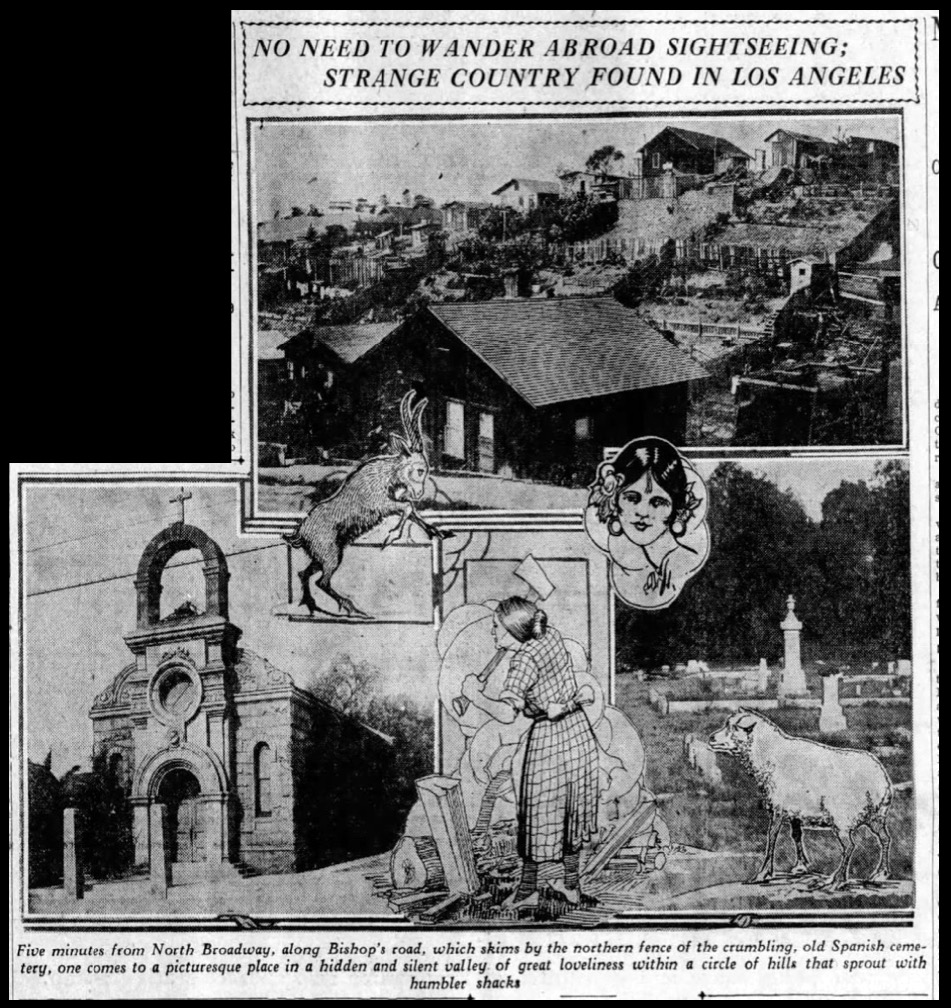

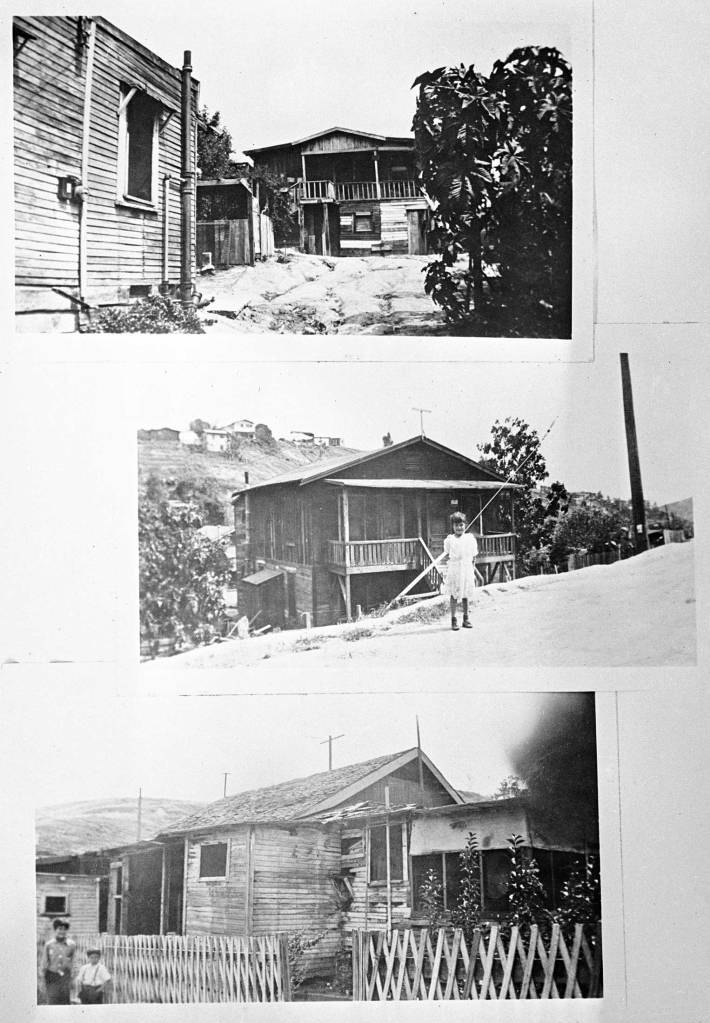

In 1928, the Evening Express published an engrossing description of Chavez Ravine, a “picturesque place in a hidden and silent valley of great loveliness.” It describes the “humble shacks, unpainted except by the elements” and the usual suspects: a man pushing a tamale cart, a woman chopping wood, dogs sleeping in the streets. Houses are built of old packing cases, and surrounded by guava trees; at night the people dance as the sheep graze. Modern sensibilities will bristle at the 100-year-old tone of the depictions, but it remains an intriguing early portrait, by the always-fascinating Theodore Le Berthon. Read the piece in its entirety here.

Come the 1930s Chavez Ravine persevered—along with the rest of America—through the Great Depression, and building slowed considerably. The end of the decade saw us plunged into wartime. A WWII-era image from the chapel of Santo Niño:

The south end of Chavez Ravine saw the construction of the U.S. Naval & Marine Corps Reserve Armory, which broke ground in 1938; it was presented to the 11th Naval District by the WPA in October 1940, and its first reservists marched in September 1941, just months before the Axis attack on Pearl Harbor.

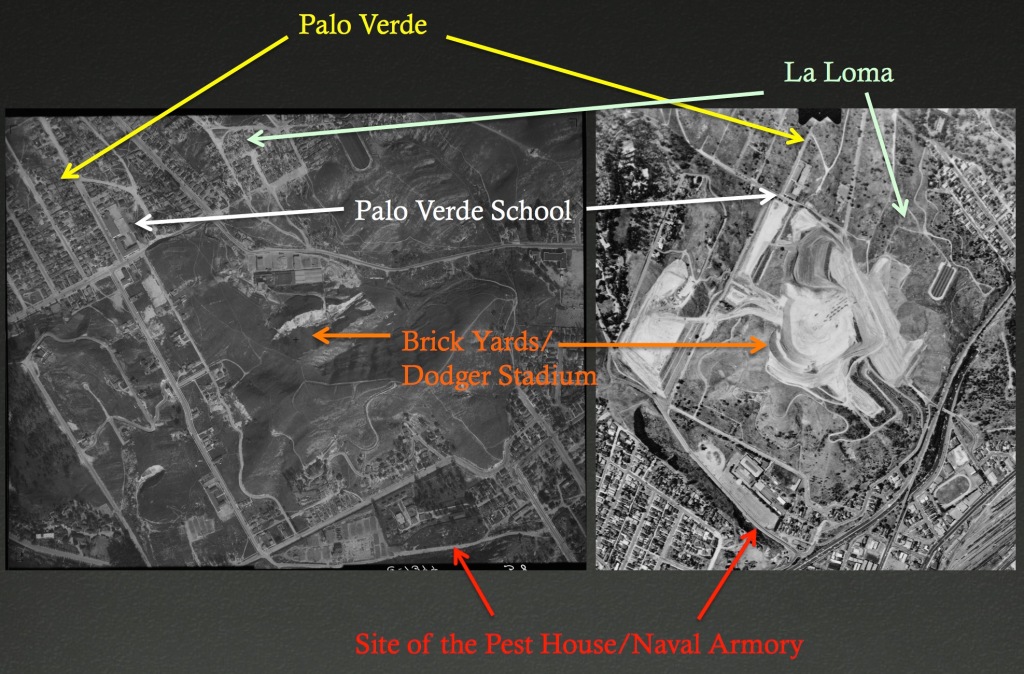

The scattered houses on the rise behind the Armory are on Lookout Drive, on Mount Lookout. To give you an idea as to the location of the Naval Armory in relation to greater Chavez Ravine neighborhoods, take a look at this aerial comparison from February 1931 and May 1960:

The Reserve Center plays an important part of Los Angeles lore in general, and Chavez Ravine in particular. Soldiers stationed and trained there became embroiled in violent altercations with local men expressing anti-American sentiment, resulting in the famed sailor-pachuco unrest of June 3-8, 1943, commonly known as the “Zoot Suit Riots.”

One more shot of the the area:

And, because I feel like I have to repeat this one million times, no, nobody’s house is under second base…

Ry Cooder famously sang “2nd base, right over there, I see grandma in her rocking chair” and it made a whole generation of people think that’s a real thing. Second base? Site of an abandoned brick yard. I know Cooder was being metaphorical, but that’s not how one single person ever took it.

Another map, this time from 1943:

II. Early Demolition Plans for Chavez Ravine

Much like Bunker Hill—which, before it was chosen for massive redevelopment by the Community Redevelopment Agency in 1949, had weathered multiple proposals for total demolition dating back decades—Chavez Ravine had outlasted other redevelopment plans.

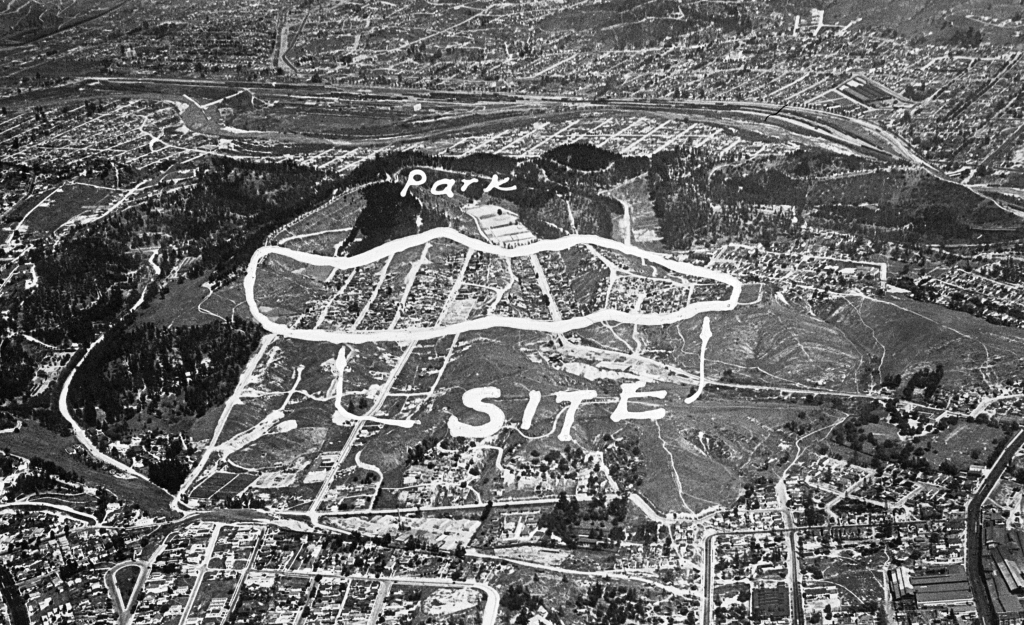

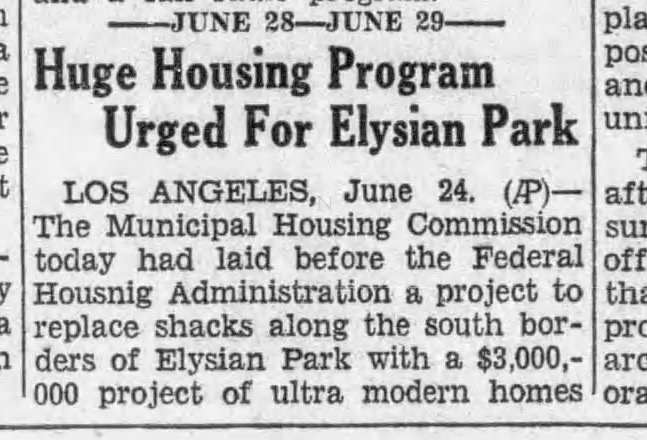

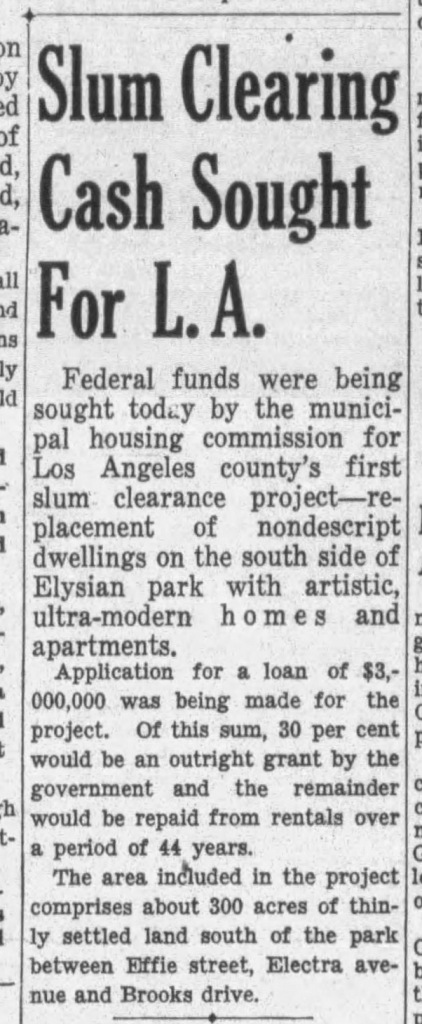

In 1935, the entire area of Palo Verde and La Loma was slated for redevelopment:

It was the intention of the Municipal Housing Commission to replace the “shacks” with “artistic, ultra-modern homes and apartments”—

This was part of Mayor Shaw’s slum clearance plan that began in 1934, dependent on Federal money. After the passage of Roosevelt’s 1937 Housing Act, Shaw and the City Council established the Los Angeles Housing Authority in March 1938. By August Shaw had secured $25million in Federal monies for slum clearance (which his mayoral successor Fletcher Bowron used to appropriate and clear 175 acres to build ten housing projects by early 1942), but by that time, Chavez Ravine had been earmarked for a new project:

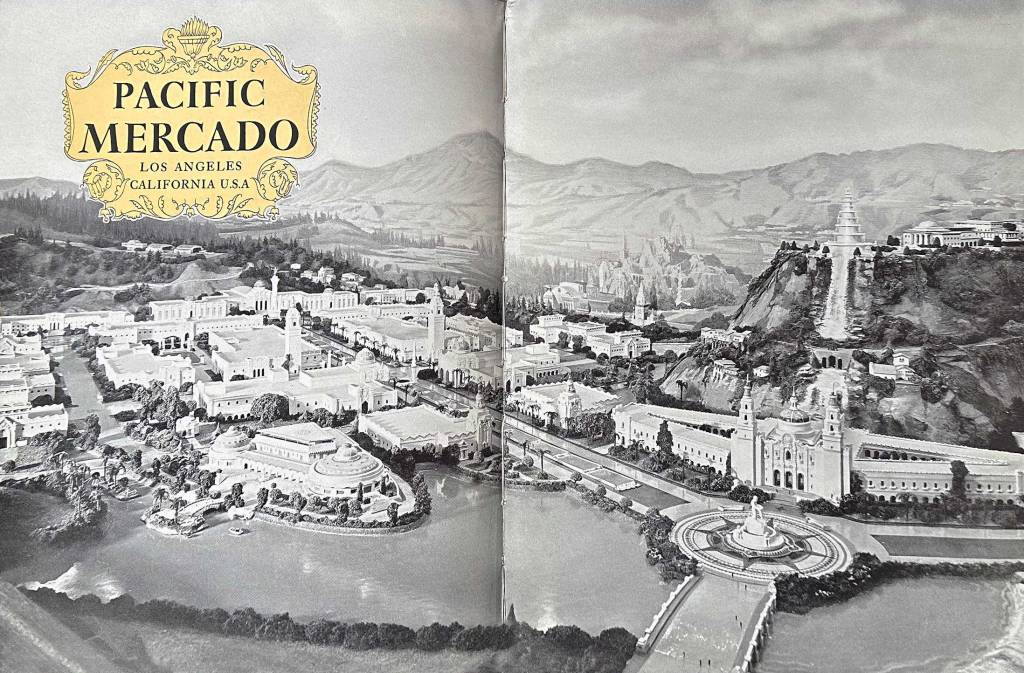

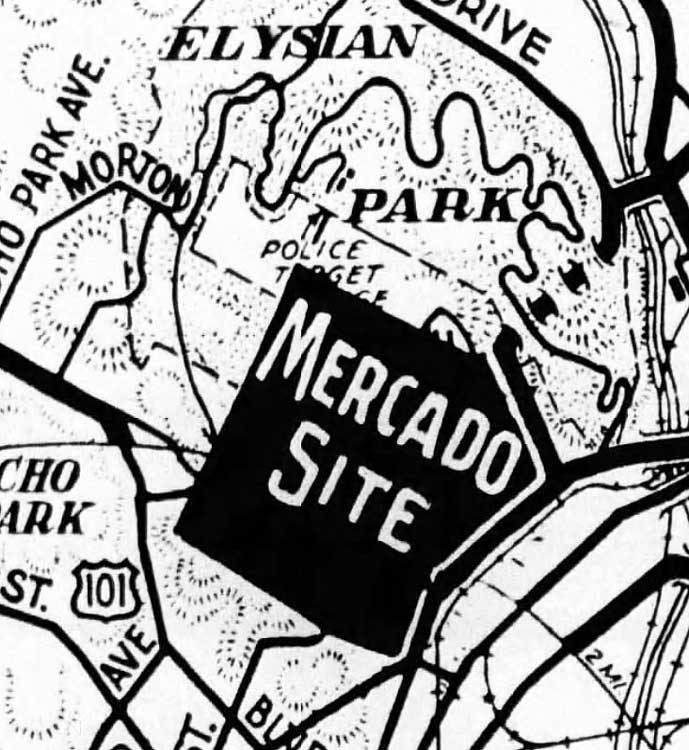

This was to be the Pacific Mercado World Mart and Exhibition, a 400-acre affair to open in 1940, and hosting a World’s Fair to commemorate Cabrillo in 1942. It would have consumed all of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop:

But that was not to be, either. Much of the area was taken by the Feds for the aforementioned Naval/Marine Reserve Station and Armory, and with the onset of WWII, plans for Chavez Ravine stalled for the rest of the 1940s.

We will examine how folk lived their lives in the Ravine in the 40s come this Tuesday’s installment, but first:

III: Are You Allowed to Call it Chavez Ravine?

People will scold “you can’t say Chavez Ravine! You have to call it La Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop!”

Well, you can go ahead and call the area those three names, and please do so to your heart’s content.

There is, however, no reason for anyone else not to refer to the whole area as Chavez Ravine. After all, when you’re talking about New York City, no-one yells at you “you have to call it Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island!”

For example, I have a buddy from Watts—whose family moved there in the 1940s—and were I to mention “South Central” to him, he wouldn’t scream “you can’t use that term! You have to call it Adams-Normandie, Jefferson Park, Baldwin Hills, Leimert Park, Crenshaw, Manchester Square, Broadway-Manchester, Nevin, Central-Alameda, Chesterfield Square, Exposition Park, University Park, South Park, Florence, Vermont Knolls, Gramercy Park, Vermont Square, Green Meadows, Vermont Vista, West Adams, Harvard Park, Vermont-Slauson, Hyde Park, and Watts!” He wouldn’t insist I was trying to “erase Watts” when I spoke about the places that comprise South Central as South Central. Because that would be dumb.

“But Chavez Ravine is just…a made-up name for the area!” Well, so are the names La Loma and Bishop. (Palo Verde at least makes sense because some fifty-year-old real estate developer named Riggins developed a subdivision, laid it out, and named it the Palo Verde tract.) People go on about how the communities of Bishop, La Loma, and Palo Verde were “founded,” except they weren’t founded, rather, some vaguely-defined areas were given nicknames: Bishop because it was somewhat near Bishops Road, and La Loma because it was on a hill.

Consider Bunker Hill. An area bounded by Hill Street, Figueroa, Fifth, and Temple: when the area was laid out by Beaudry and Mott in the 1860s, it wasn’t known as Bunker Hill. But, there was a Bunker Hill Avenue that ran through it. About thirty years later, boom, the whole area had become known as Bunker Hill (at which point, no-one talked about Bunker Hill neighborhoods like Olive Heights anymore).

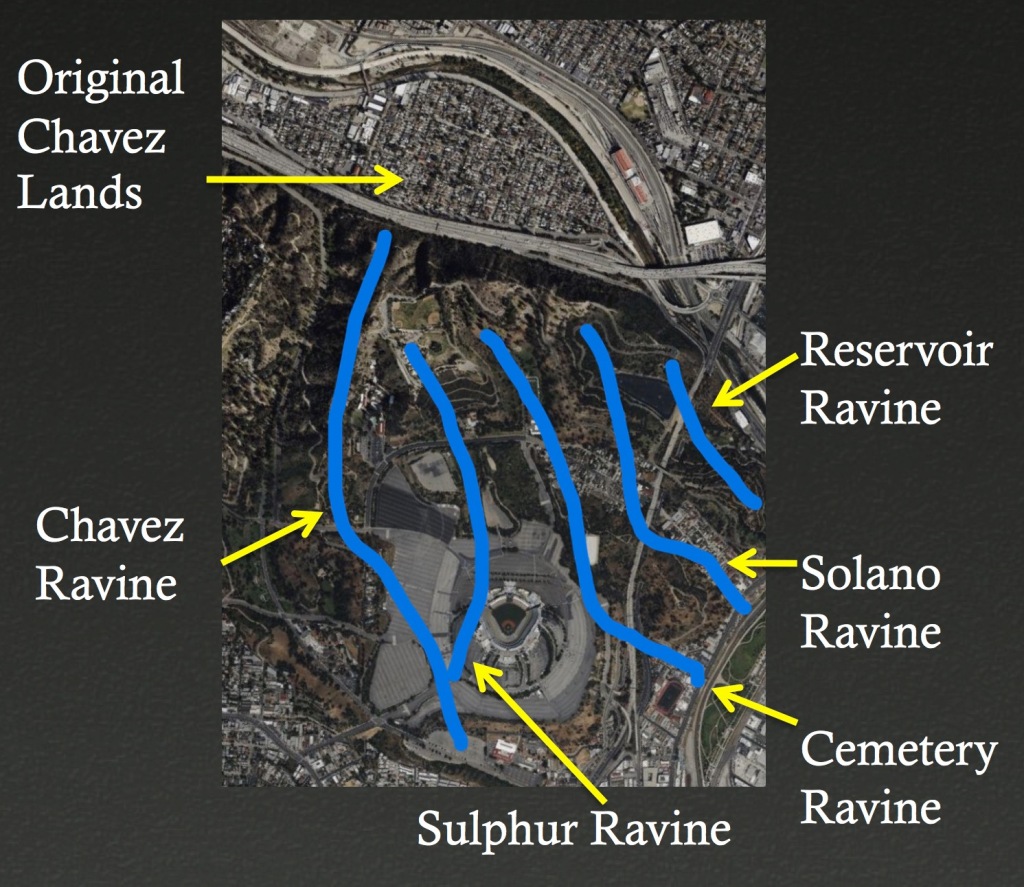

See how that works? The part gives the name to the whole. Same thing happened here: the greater area adjacent Chavez Ravine became known as Chavez Ravine. Beats calling it Sulphur Ravine, right? Or Cemetery Ravine? (Actually I think that would be cool.)

And consider this: when you are a big muckety-muck, you get large tracts of land named after you—à la Van Nuys, Baldwin Hills, Griffith Park, Glassel, Wilshire, Silverlake, Sherman Oaks, and so on. Julián Chávez was an important person, so it’s an honor, for him and us, that the place in general is named after him. I would understand if people got in a twist had it been named Norris Poulsonland, but it wasn’t. Why are you hating on poor Julián Chávez so much?

“But calling it Chavez Ravine is a racist thing the Dodger corporation made up to erase us!” Eh, nah. The vaster area, and those particular places within it, was referred to as Chavez Ravine dating back to the 1920s. For example:

“The people from La Loma, Palo Verde and Bishop never called it Chavez Ravine!” Really? Because here’s a picture from 1953 of a Palo Verde woman literally referring to her neighborhood as Chavez Ravine.

When Arechiga descendants fingerwag and inform us no resident ever referred to themselves as Chavez Ravine, here’s literally a picture of the family—Melissa Arechiga’s great-great grandmother Abrana Arechiga with her great aunt & uncle, residents of Palo Verde—referring to themselves as Chavez Ravine:

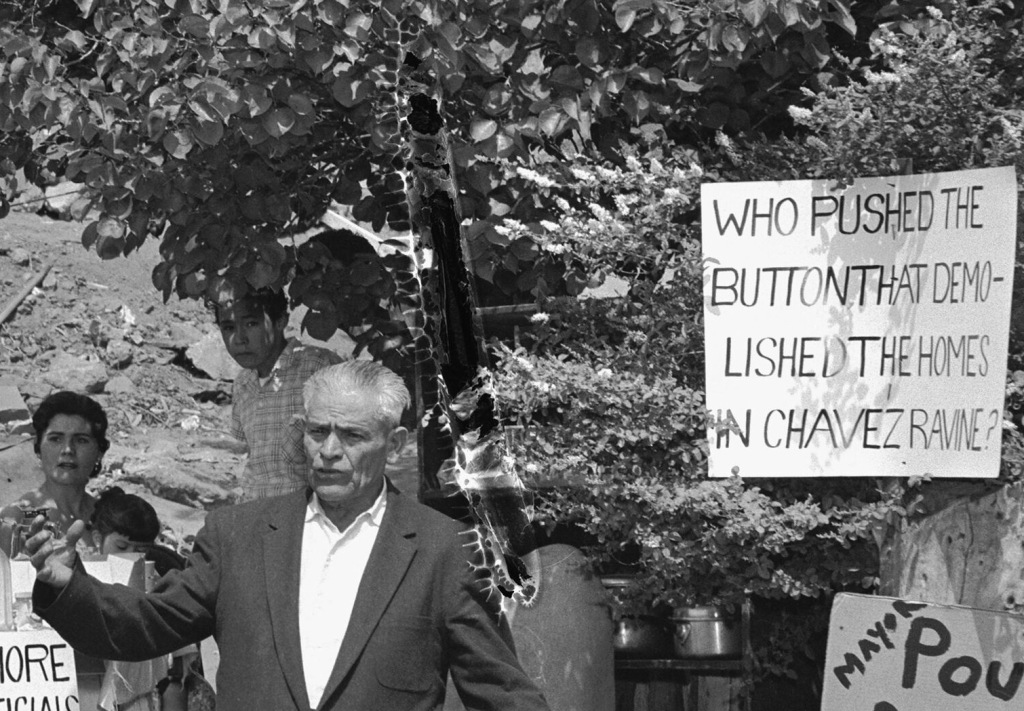

And again: here is the patriarch of the Arechiga clan, Manuel Arechiga, in Palo Verde, with a sign that talks about “the homes in Chavez Ravine”—

So, that’s my take on the whole “you’re not allowed to call it Chavez Ravine” directive from on high: anyone who feels the burning need to call Chavez Ravine something other than its name, have at it, but don’t be upset if your attempts to “school” the rest of us fall flat.

So now you have a decent handle on the what and where. Next time, in Chapter III: Calm Before the Storm we’ll develop a snapshot of life in Chavez Ravine, and talk a bit about the people and their daily lives in the late 1940s, before everything changed.

This is seven-part series. Its component parts being:

Part I: Chavez Ravine and the Mainstream Narrative

The master narrative, as promulgated by the mainstream media; its result, a reparations bill; the good and bad of that bill. Published Friday, May 10.

Part II: What is Chavez Ravine

Its beginnings, development, and evolution to 1950; its history of demolition prospects; and, can you call it Chavez Ravine? Published today, Sunday May 12.

Part III: Calm Before the Storm

A snapshot of life in the area in the 1940s. The mythos of small-town life; Normark’s documentary work; a study of the people of Chavez Ravine; churches, markets, bus lines, etc. To be published Tuesday, May 14.

Part IV: The Rise and Fall of Elysian Park Heights

A history of public housing; Neutra’s Elysian Park Heights project; its proponents and opponents; the area’s demolition; the downfall of public housing, and its relationship to anticommunism; land use after the demolition and nullification of the contract. To be published Thursday, May 16.

Part V: Here Come the Dodgers

About the Dodgers; what constitutes public purpose; an illegal backroom deal?; a stadium is built. To be published Saturday, May 18.

Part VI: The Arechiga Family

The Arechiga family history to 1950; eviction from Malvina Street; eventual removal in May 1959; the multiple Arechiga houses; life after Malvina; the next generation of Arechigas. To be published Monday, May 20.

Part VII: In Summation, plus Odds and Ends

Key takeaways; plus a collection of *other* commonly-held beliefs about Chavez Ravine, conclusively debunked. To be published Wednesday, May 22.

If you have comments or corrections, please don’t hesitate to write me at oldbunkerhill@gmail.com.

Wow, Nathan! Looking forward to this read!

LikeLike

I may not agree with your politics, and I find it difficult to dispute your facts. Great Work!

LikeLike

Thank you! Ha ha, nobody likes my politics, so no worries! And thanks for the thoughtful response (this town being one big echo chamber, people usually get super butthurt any time they encounter anything that deviates slightly from the governing dogma).

And yes! I believe facts are everything, facts are the only thing…unfortunately, that makes people crazy when the facts contradict some piece of family lore…

My politics may be different than most people are used to, but at heart we all believe the same thing—save old houses, save old neighborhoods, respect the traditions of communities. Have you read my stuff over at RIPLosAngeles? Fighting greedy developers and other Los Angeles-destroying idiots one post at a time!

Oh and hey I *love* your work on #saveelpino! I believe in trees above all things (like El Pino and the Cornelius Johnson Oak), and was part of the restoration of Bunker Hill’s Moreton Bay Fig, and “Sunshine” the Queen Palm.

Ever onward!

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful response. I believe in the #SaveElPino movement and we started SaveElPino.com to counter the argument that the developer’s family (the infamous Art Gastelum) narrative which totally (totes) promises to not hurt El Pino with their condos.

I’ve actually worked with the BUtB folks and helped get them in the LA Times with their Displacer banner and I had a falling out with them when I dared to ask questions about original documents. I was curious and as a die hard baseball and Dodger fan, I was willing to forgo my fanhood if the facts proved the Dodger had a role in displacing the 3 communities and to date I have not seen a single shred of evidence.

I’ve been fighting for nearly 5 years to save a majestic Bunya tree because my primary concern is the gentrification of East LA and having grown up in Frogtown and after seeing my family personally impacted by displacement has helped me to defend the tree and the Chican@s despite the owner and his daughter’s best efforts to stop me from defending the barrio and El Pino in East Los Angeles.

Keep up the Great Work and Bunker Hill is one of the most important communities in Los Angeles history and the film The Exiles remains one of the best visuals examples of the neighborhood in it’s waning glory.

LikeLike