Our story so far: we introduced our subject in Part I by detailing how Chavez Ravine’s popular mainstream narrative is aggressively counterfactual. Part II answered the question of “what is this Chavez Ravine?” Part III gave a rough sketch of what life was like in Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop during the postwar era, before it was depopulated. Part IV ran us through the history of the Elysian Park Heights project, under whose aegis the area was cleared.

Today! You’ve probably heard of the Dodgers. And you know their stadium is in Chavez Ravine. How did they get there? Let’s find out!

I. A Team Called the Dodgers

In the previous installment we dealt with Chavez Ravine as it related to postwar public housing projects and the subsequent demolition of homes in the Ravine, etc.

During that time, out in Brooklyn, there was a baseball team called the Dodgers. They played at an aging (built 1913), small stadium, with little parking, called Ebbets Field. The team and stadium were owned by a fellow named Walter O’Malley.

O’Malley was in the works to build a new, capacious, privately-owned domed baseball stadium on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, but was thwarted by government. New York City Building Commissioner Robert Moses insisted it be a city-owned stadium, and had to be located in Queens. O’Malley and Moses battled over this for years on end, both certain they’d get what they want.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles had been hot to get a major league team for a very long time, and we pestered all sorts of teams to give Los Angeles a shot at relocation. In 1955 the City Council wrote a letter to O’Malley to say heyyy, we could use a team here, but O’Malley brushed them off. (Some people will try and tell you that when Council attempted to court O’Malley in 1955, that these communiques involved Chavez Ravine and somehow prove a conspiracy against La Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop. That is, of course, a fiction; it’s nonsense on the face of it, since those neighborhoods were already depopulated and demolished pre-1955. But much more revealing: here’s a “Buried Under the Blue” post alleging Council’s letter reveals we were attempting to displace Ravine denizens and destroy its neighborhoods in 1955…and here again is another one…but then you read the actual letter and it says nothing about Chavez Ravine.)

In late 1956 O’Malley was in Los Angeles, and even gave a speech about how and why he would not move the Dodgers to Los Angeles.

O’Malley had been working for ten years to replace Ebbets Field, stymied by Moses, and was hoping against hope he’d still be able to build his dream stadium in Brooklyn. But by the spring of 1957 he’d had enough of New York’s corruption, so he looked to sunnier climes.

In May 1957 we finally got O’Malley out to Los Angeles, to look at a half-dozen prospective sites. O’Malley goes up in the whirlybird—May 2, 1957—and from the air examines Wrigley Field (which O’Malley had acquired the previous February) and the Coliseum, etc. But then O’Malley saw the stacks, AKA the famous four-way freeway interchange, right next to a huge piece of empty land.

He had seen Chavez Ravine, and concluded if he was going to spend twenty million dollars out of his own pocket to build Los Angeles a stadium, that’s where it was going to be located.

The city had zero money for any of its lofty and various Ravine plans (lake/college/zoo/expansion of the Police Academy, etc., much less a massive ballpark). The idea that someone else would spend the millions to build a 50,000-seat stadium was a godsend.

There exists a persistent mythological narrative that the City had always planned to displace the people of Chavez Ravine for a stadium. Not only is that not true, as borne out by the simple chronology of events, but there is a paper trail to prove that contention false. A July 1956 Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks study, investigating the idea of a stadium in a dozen some-odd places around Los Angeles, noted this about Chavez Ravine, when it dismissed the idea: “The rugged topography of this area does not appear to be desirable for the proposed use,” adding “most of the property considered for this use is owned by the City of Los Angeles and is vacant. Abutting land is in private ownership and, except for a few small residences, is vacant.” So not only did they note the area to be vacant (when revisionists say it wasn’t) the Powers That Be still didn’t consider it useful stadium territory.

II. Regarding Public Purpose

The City had long since repurchased their land from the Feds, so it belonged to the City to do with as they pleased. There existed the stipulation—as written into the Housing Authority deed transfer—that the land be used for a public purpose. A lot of people will yell at you that “a baseball stadium is not a public purpose!”

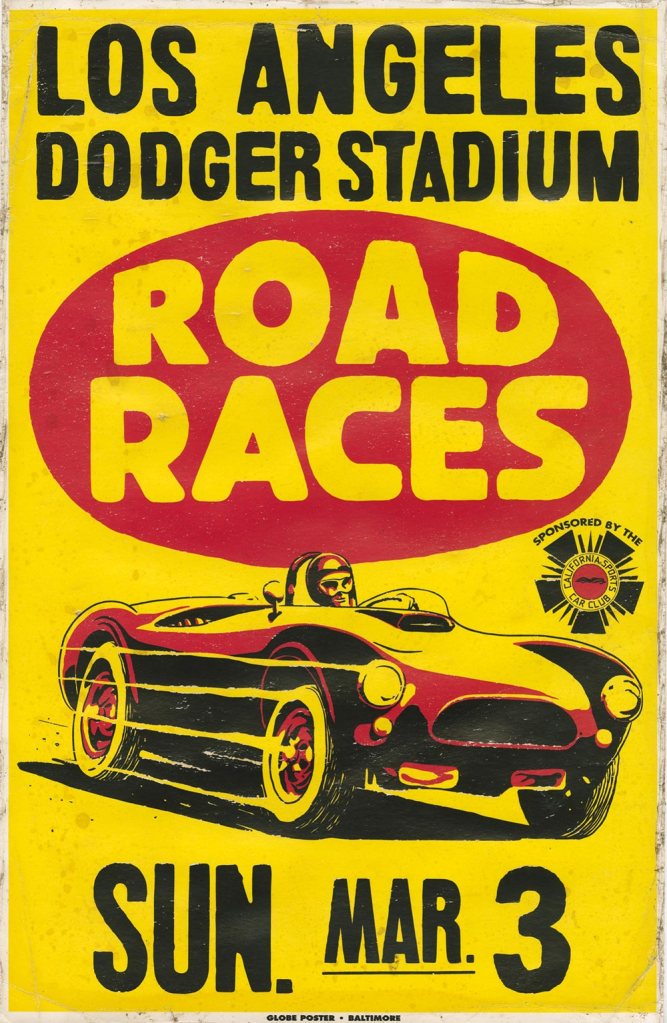

Um, when there’s 56,000 people there, I fail to think of a better definition of public purpose. I’m not a sports guy and personally don’t care about baseball—but I do acknowledge there’s enormous public purpose value to the vast civic pride the Dodgers bring. Above and beyond the Dodgers, I remember when 56,000 people were crammed therein to see John Paul II perform mass. People also filled it to see The Beatles and Bowie and the Stones and Springsteen and Guns n Roses and Michael Jackson, and on and on (even Elvis, sort of, who filmed Spinout in the stadium parking lot) … speaking of race cars and public purpose, did you know there used to be awesome road races in the parking lot?

Anyway, I say that fits the definition of public purpose, though some certainly insist it does not, but…

… you want to know the kicker? The whole “public purpose” clause of the Housing Authority deed restriction was made void by the Court in a unanimous decision anyway, so there’s literally no reason for people to talk about it … but they sure do anyway. In short: the CHA transferred the land to the City with the “public purpose” clause, that did not in any way define what “public purpose” actually meant or entailed. Arguments over the public purpose deed restriction were made in trial courtrooms through the summer of 1958 in Los Angeles Superior Court. The matter went to the State Supreme Court, where it was decided the the public purpose restriction had in fact been fulfilled.

But oh! they continue, that may be true buuuuut….public purpose doesn’t have to be legal, it’s moral, and all that civic pride is only just making money for the owner, it’s therefore immoral and not a public purpose! Well if we’re going to talk about money: Chavez Ravine, before its condemnation by the government, containing all those La Loma/Palo Verde/Bishop residents, paid a yearly sum total of $7,400 in property taxes. In the first year after having opened the stadium, the Dodgers paid $345,000, a 50-fold increase of money into the City coffers. Over the last sixty years the Dodgers have paid nearly a billion dollars into the City coffers just from property taxes. Not to mention the state and local taxes, employment opportunities, entertainment spending, and so forth. When the City spends money on roads, schools, wastewater treatment, public safety, and all that jazz, a billion dollars of that money came to the city via a private entity building a stadium on their own dime.

Again, the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of public purpose in January 1959 (City of Los Angeles v. Superior Court) when it said that the contract with the Dodgers brought such enormous benefit to the City, and had thus fulfilled and nullified the deed restriction. After which, the California Supreme Court unanimously sustained its ruling repeatedly through 1959.

But oh! you will be instructed, the city should have built its own stadium, then it would be *ours*, and not in the private hands of dumb private people! Sorry, but as I just mentioned, in the late 1950s the City of LA did not remotely have that kind of money to build a stadium, and if we had, the City would never have received that $1billion in property taxes.

But because I hear a lot about how the City lost out because it did not build its own municipally-owned and run stadium, let’s devote a few paragraphs to the difference between the privately-funded, and the taxpayer-funded, American ballpark:

Now remember, a privately-funded ballpark is as rare as hen’s teeth…for a reason. Yes, Walter O’Malley got two 99-year leases for $1 a year—cue the chorus of it’s a backroom deal conspiracy and he stole the land!—but the fact stands, he spent $23million out of his own pocket to build the stadium (oh, and before you say he was “given” the land, nope, he deeded land he owned, worth about $2million, to the City of Los Angeles, in exchange for Chavez land, worth about $2million). Then O’Malley spent his $23million to build the stadium, which, adjusted for inflation he therefore spent, in today’s money, $242million. That’s a quarter of a billion dollars out of O’Malley’s pocket to build the stadium, which, 62 years later, remains an exceptional stadium.

Conversely, from the 1920s to the 60s, all the major American ballparks were constructed as municipal stadiums, built by local governments, paid for by taxpayers. The last privately funded baseball stadium had been Yankee Stadium, and that was in 1923. So when people say the City of Los Angeles could have/should have built the stadium itself instead of having someone else do it, remember again, we didn’t have the money, and more importantly: municipally-constructed stadiums are crap.

You read that right, total crapola. After all, look at taxpayer-built Candlestick Park or Shea Stadium. Oh wait you can’t, they’re both demolished. Milwaukee stadium, built with public funds in 1953, torn down. Kansas City, built with public funds in 1955, demolished. It’s an amazing fact to consider, but a dozen-plus major league baseball stadiums have been built and torn down just during the time since Dodger Stadium opened in 1962.

Municipal stadiums, being government owned and run, suffer (or, more likely, suffered) one and all from bad design, poor maintenance, and cost overruns.

Dodger Stadium, though, being privately built and owned, remains as a monumentally important piece of architecture, and an actual, functional stadium. Because O’Malley said “I want the largest and most modern stadium in the world,” that’s what he paid for, designed by Emil Praeger of Praeger-Kavanagh-Waterbury. It’s the third oldest baseball stadium in the US, after Wrigley and Fenway (which both predate WWI).

And irrespective of it housing the Dodgers, it’s an amazing piece of Mid-Century Modern, with those folded plate roofs and inverted canopies and martini glass planters; it embodies all the futuristic optimism that defines postwar Southern California.

Here in Los Angeles the last time we built a stadium was in Inglewood. It opened a couple years ago, after a guy named Stan Kroenke spent three billion of his own dollars on the thing. Now he’s on the hook to make sure his investment pays off. If it were run by local government, well, you know how that would go.

III. Illegal Backdoor Deals!

The stadium and the team is there in Chavez Ravine, and you will be told “it’s because of illegal backdoor deals!”

Um, no. Not only was the whole enterprise under intense public scrutiny, and approved by the City Council after lengthy debate, and approved by the courts (up to and including the California Supreme Court), it actually went to the voters. The terms of the much-debated October 1957 contract were pretty simple: O’Malley would deed a piece of land to the City (Wrigley Field) valued by city appraisers at $2.2 million, and in an even swap, the City would deed Chavez land to O’Malley, valued at city appraisers at $2.2 million. Then, O’Malley would build a 50,000-seat stadium out of his own pocket.

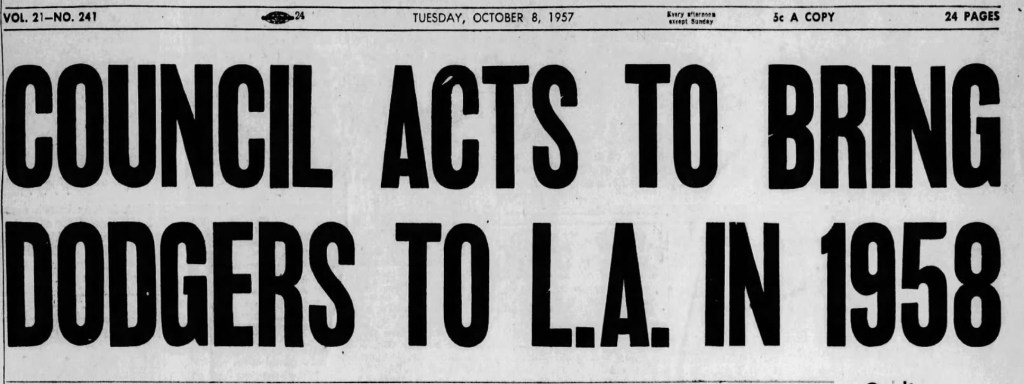

This was put before the City Council, who approved it.

It was then handed to the People of Los Angeles who, like the City Council, could have tanked the whole thing and put Chavez Ravine back to square one:

Not only was the Dodger contract approved by the voters, but the Ninth District—which covered the Chavez Ravine area and was represented by Councilman Ed Roybal—had one of the largest margins of approval for the referendum.

So, never having been engaged in an “illegal backroom deal” maybe I don’t know what one is, but I can absolutely tell you what it’s not: something endlessly hashed out in the press and by the courts, and thereafter being approved by City Council, and then being approved by the majority of the voters. The Council or the people of Los Angeles could have easily nailed the Dodger coffin lid shut and sent them packing, if franchise relocation and stadium-building had in fact been the violent and criminal thing we are constantly led to believe. Dodger relocation, the Chavez Ravine deal, and so forth: exactly the polar opposite of anything illegal or “backdoor.”

One more thing. In June 1958, after the voters approved Dodger Stadium, Judge Arnold Praeger said “I don’t care what the City Council and people of Los Angeles say, I rule the City’s contract with the Dodgers as invalid!” At which point the California State Supreme Court voted unanimously (7-0) to reverse Praeger’s decision, and Chief Justice Phil B. Gibson embraced the Supreme Court ruling, to uphold the contract between the City of Los Angeles and the Dodgers, for which the citizens of Los Angeles had voted. Again, literally the opposite of a backdoor deal.

Anyway. Groundbreaking for the stadium is September 1959, and it opens in April 1962, and that is that. Hey, I don’t know from baseball, but there are few things I love more than a Japanese garden.

Before groundbreaking, however, the final holdouts had to be removed. That story, coming up next in Part VI: The Arechiga Family!

**********

This is seven-part series. Its component parts being:

Part I: Chavez Ravine and the Mainstream Narrative

The master narrative, as promulgated by the mainstream media; its result, a reparations bill; the good and bad of that bill. Published Friday, May 10.

Part II: What is Chavez Ravine

Its beginnings, development, and evolution to 1950; its history of demolition prospects; and, can you call it Chavez Ravine? Published Sunday, May 12.

Part III: Calm Before the Storm

A snapshot of life in the area in the 1940s. The mythos of small-town life; Normark’s documentary work; a study of the people of Chavez Ravine; churches, markets, bus lines, etc. Published Tuesday, May 14.

Part IV: The Rise and Fall of Elysian Park Heights

A history of public housing; Neutra’s Elysian Park Heights project; its proponents and opponents; the area’s demolition; the downfall of public housing, and its relationship to anticommunism; land use after the demolition and nullification of the contract. Published Thursday, May 16.

Part V: Here Come the Dodgers

About the Dodgers; what constitutes public purpose; an illegal backroom deal? Published today, Monday, May 20.

Part VI: The Arechiga Family

The Arechiga family history to 1950; eviction from Malvina Street; eventual removal in May 1959; the multiple Arechiga houses; life after Malvina; the next generation of Arechigas. To be published Thursday, May 23.

Part VII: In Summation, plus Odds and Ends

Key takeaways; plus a collection of *other* commonly-held beliefs about Chavez Ravine, conclusively debunked. To be published Sunday, May 26.

If you have comments or corrections, please don’t hesitate to write me at oldbunkerhill@gmail.com.

Part six is late. I think the Arechiga family got to Nathan.

LikeLike

Ha ha! Not yet!

VI is on its way, had an emergency so got a little behind in the posting…

LikeLike