We all love great painters, especially those who depicted Los Angeles, right? And, subset of subset, specifically those who gravitated to Bunker Hill, capturing its picturesque charm.

Some favorites: the enchanting Leo Politi and his watercolors of Bunker Hill (there are libraries and schools and public squares named after the man, not to mention this exhibit). Ben Abril is well-loved for his picturesque California scenes, often focusing on old Los Angeles and Bunker Hill in particular. Emil Kosa Jr. is one of the great California scene painters and remembered for having captured Bunker Hill on his canvases; same with Victor Czerkas. And of course Millard Sheets, titan of Southern California regionalist scene painting, is best known for his masterpiece Angel’s Flight, a noirish tour de force about Bunker Hill, which hangs at LACMA.

And yet one of the greats is almost utterly unknown. Her name is Kay Martin—I love her, and you should too.

I. The Early Years

Eva Katherine Whittenberg is born in Springfield, Illinois, July 14 1910, to Eva (née Rice) and Alonzo Lindolf Whittenberg. Eva Katherine is the youngest of six girls born to Eva and Alonzo; Alonzo is a government secretary to the state of Illinois there in Springfield.

Eva Katherine grows up, and she goes by Kay. So it’s 1931, she’s 21 years old, and living in Bloomington, about sixty miles north of her native Springfield, attending Illinois Wesleyan University. There she meets a nice young fellow named Lowell Beckwith Martin—he goes by Beck. Beck is in the insurance game (his father Lester is the president of the Great States Insurance Company). Beck and Kay get married in September of ’31, lovely affair at St. Mathews Episcopal.

Kay has developed as an artist; her artistic training includes the Illinois State Normal School, where she took crafts and design, and the aforementioned Illinois Wesleyan University, where she excelled in her fine arts studies, and dug deep into the history of art and design. Kay and Beck had been married a decade and change when in 1943 they lit out for California, Glendale specifically: Lowell becomes an insurance man for Forest Lawn. Kay becomes a student of the great California landscape artist Ralph Holmes, and a student of famed English transplant California landscapist Dorothy Baugh, and a student of the unbelievably important “King of the Eucalyptus School” Sam Hyde Harris.

But she didn’t go that way, artistically, with all that plein-air painting among the trees of the arroyo, no. Back when Kay was attending Bloomington’s Illinois Wesleyan she began to developer her own style as a staunch urbanist. She depicted day workers, and WPA scenes, but once in Los Angeles her interest in the urban landscape would take her, though, down a different road from the Social Realists. Her aim was to capture the vanishing built environment, and have fun doing it.

II. The Productive Years

Kay’s living with Beck in Glendale, it’s 1955, and something catches her eye: Bunker Hill.

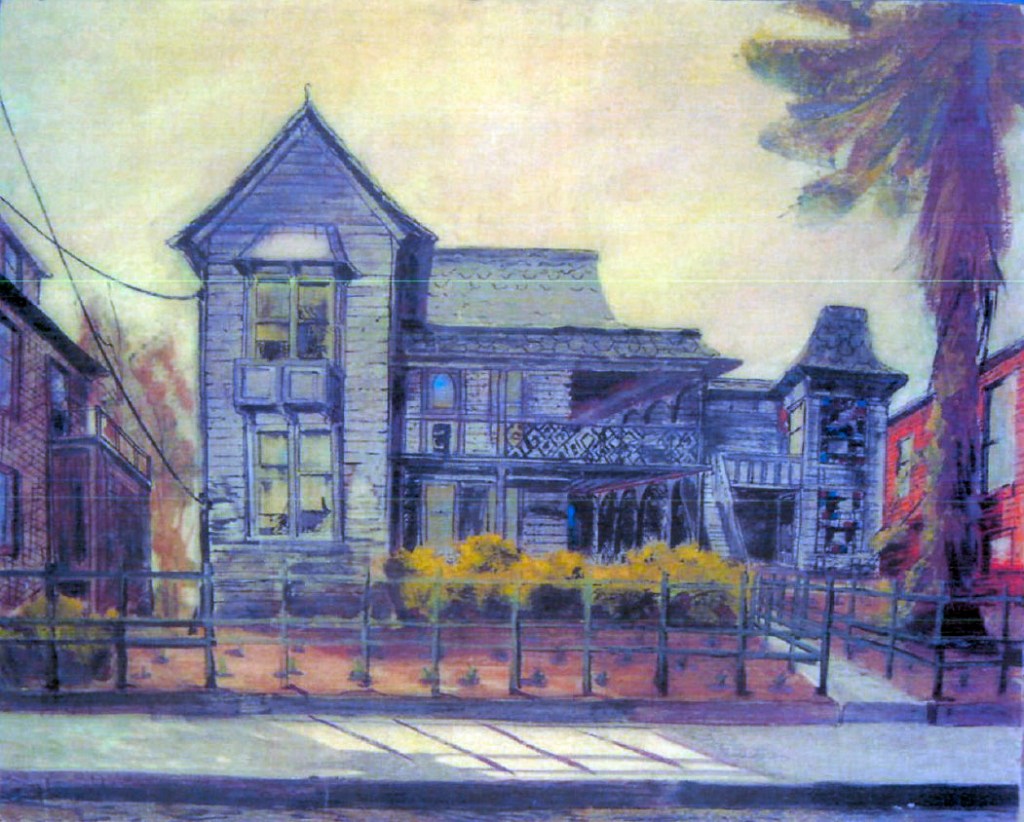

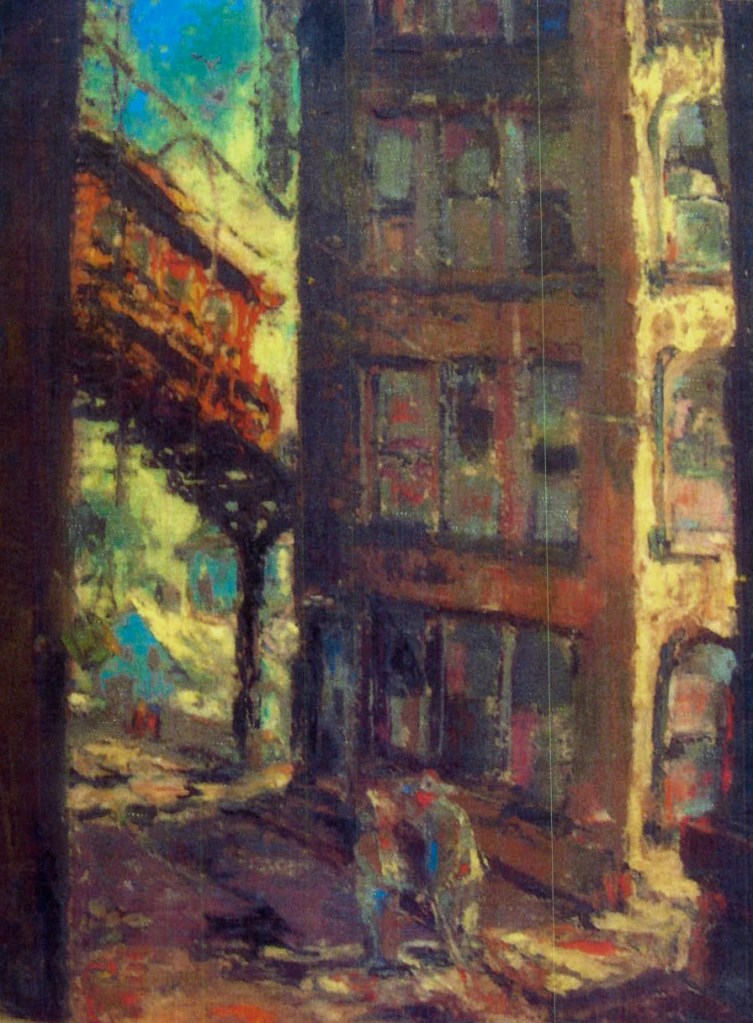

The vast swaths of Victorian buildings had been earmarked for demolition by the government and so, she set out for the Hill and began sketching. She would sketch and paint and sketch some more, and finish her paintings at home, and go back to the Hill and repeat the process. She became known as “The Vagabond of Bunker Hill.” The folks on the Hill came to know her well, and know her baby “Dreamboat,” the big white station wagon/rolling studio that came to visit the Hill near daily.

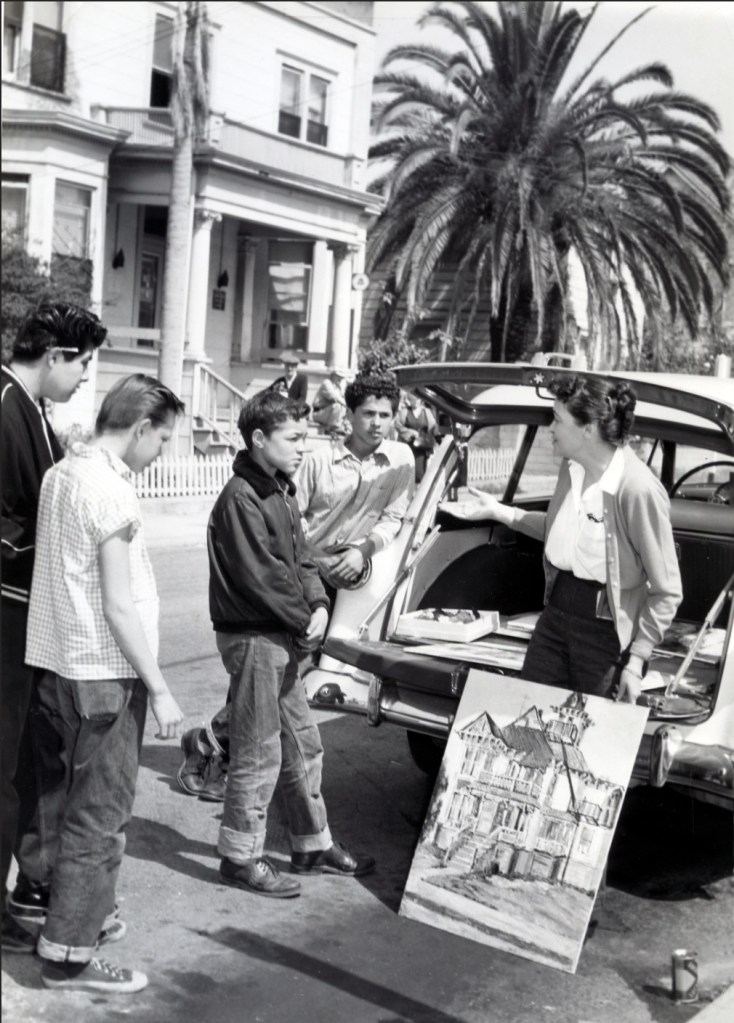

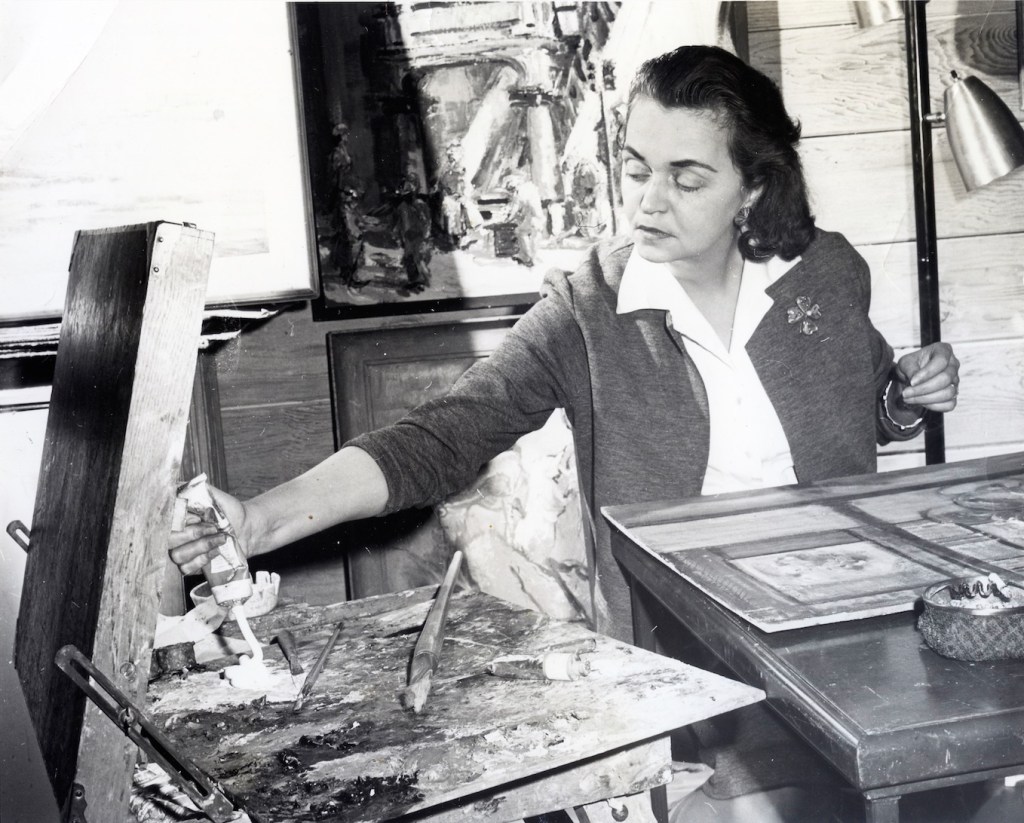

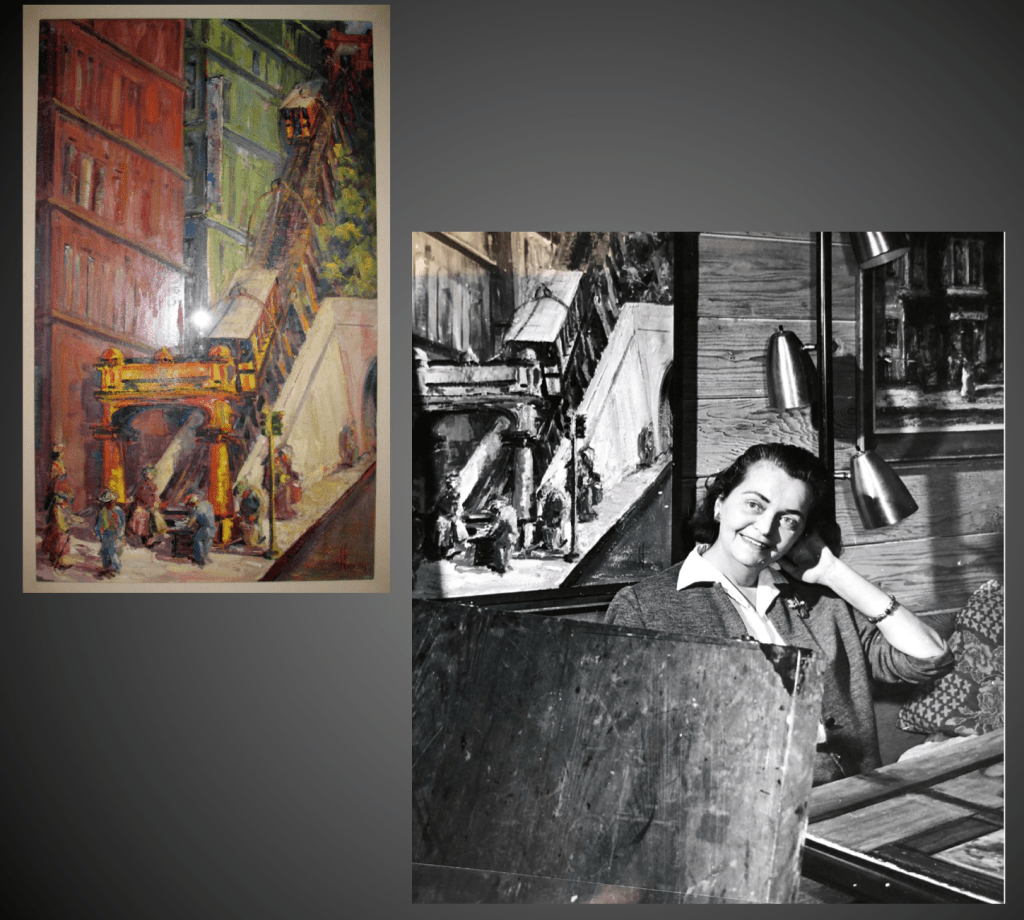

Here’s a shot of Kay at work, March 1956:

Kay’s parked across from the Earlcliff Apartments, at 231 South Bunker Hill Avenue. True to Los Angeles, there’s a Canary Island Date palm, king of palms. There’s her car, the Dreamboat, a 1952 Ford Ranch Wagon. She’s chatting up a bunch of straight-out-of-central-casting 50s teens, with their rolled-up Levis and pomade-slathered ducktail hairdos. She’s working on a painting of the Brousseau mansion which was on the south side of the street at 238, that is, out of frame foreground right.

Let’s take a look at some of Kay’s pictures.

III. Kay Martin: Exhibition, Reception, Awards, Etc.

Now you’ve seen some of her great paintings. You might wonder, were they shown anywhere? Did anyone care? Short answer: they were quite popular. They were exhibited often, won scads of awards, and received dozens of press notices.

Kay Martin’s work was exhibited at the Greek Theater, the Ebell Club, the Tropico Branch Library, and the Casa Verdugo Library. She had shows at Panorama City’s Security First National Bank, and the Bank of America in La Canada, the Glendale Mutual Savings and Loan, and Security Pacific Bank-Prudential Square.

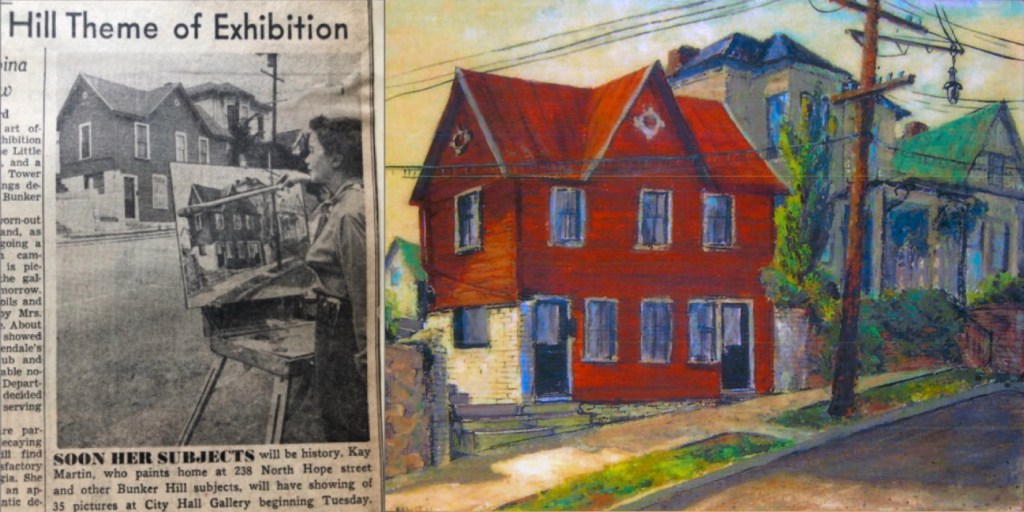

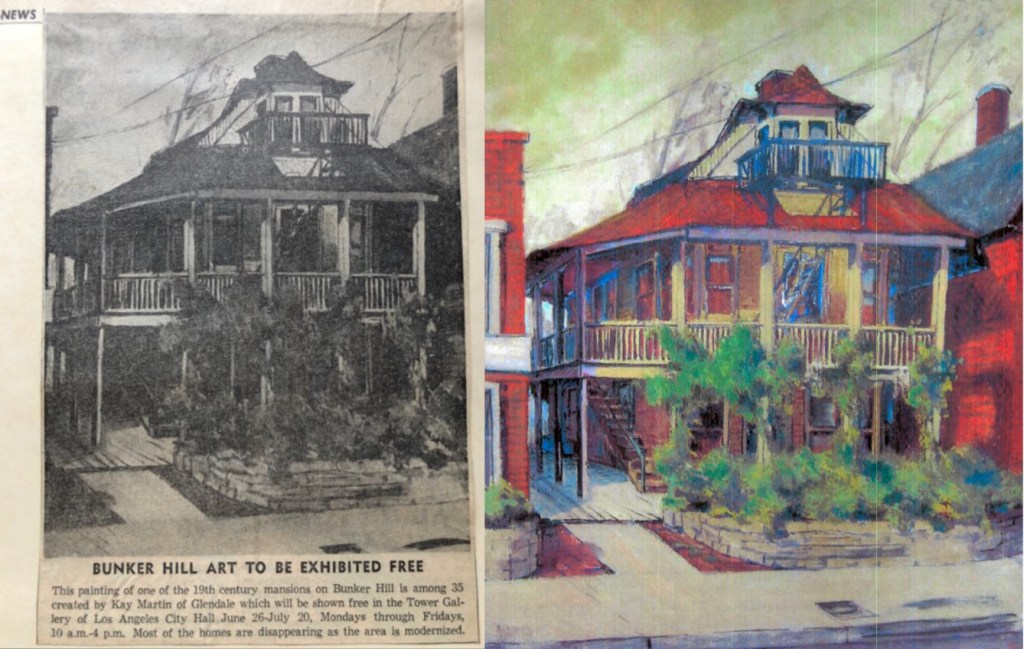

Her most towering achievement was the show in the Tower Gallery atop City Hall. It ran from June 26-July 20 1956 and featured thirty-five oils. To have a one-man show in the Tower Galley was unprecedented; that this “one-man show” was the work of a woman was absolutely groundbreaking. The show was an enormous success, garnering nearly 8,000 visitors.

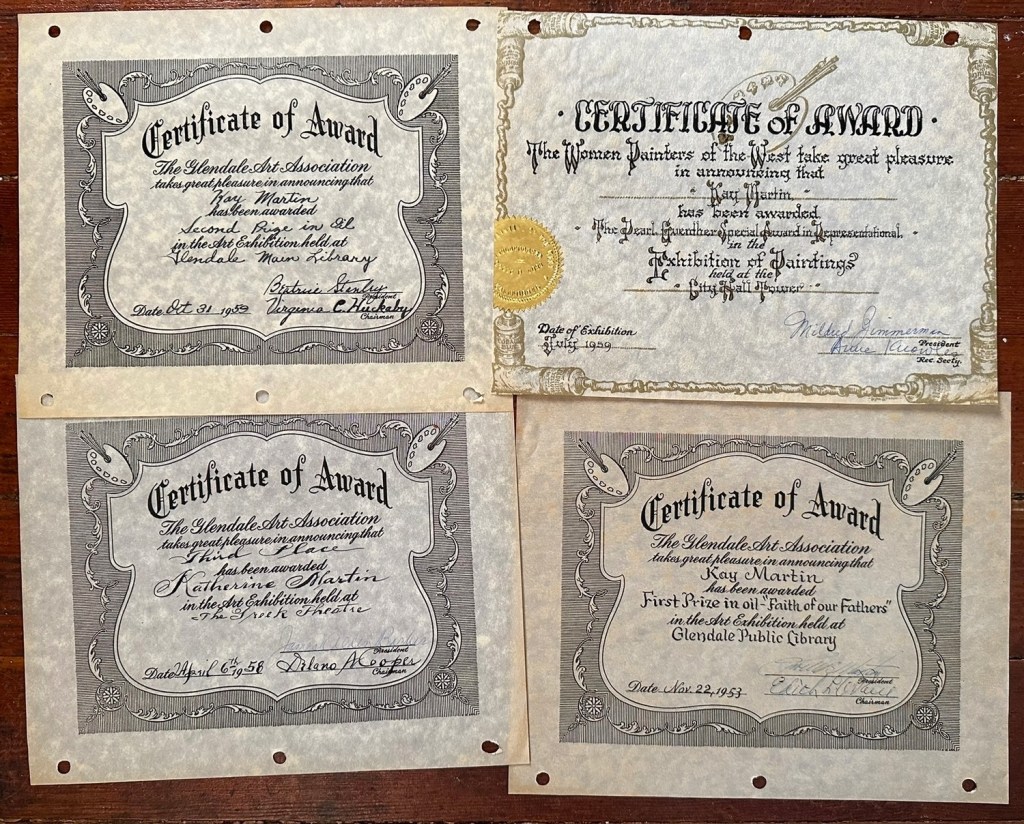

Kay Martin served as director of the Glendale Art Association, and was a bigwig in the Laguna Beach Art Association, California Art Club, Foothill Artists Group, Foothill Painters, and the group Women Painters of the West. She sat on the board of the Tuesday Afternoon Club. She lectured widely, to every art association in the southland, and spoke to a variety of civic groups and fraternal organizations about old Los Angeles.

Martin won many local and three statewide awards.

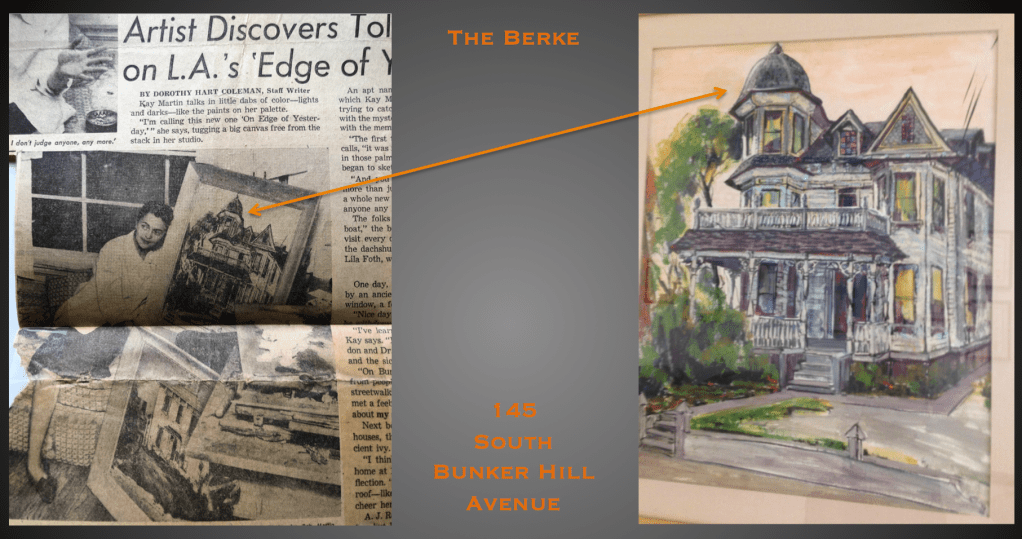

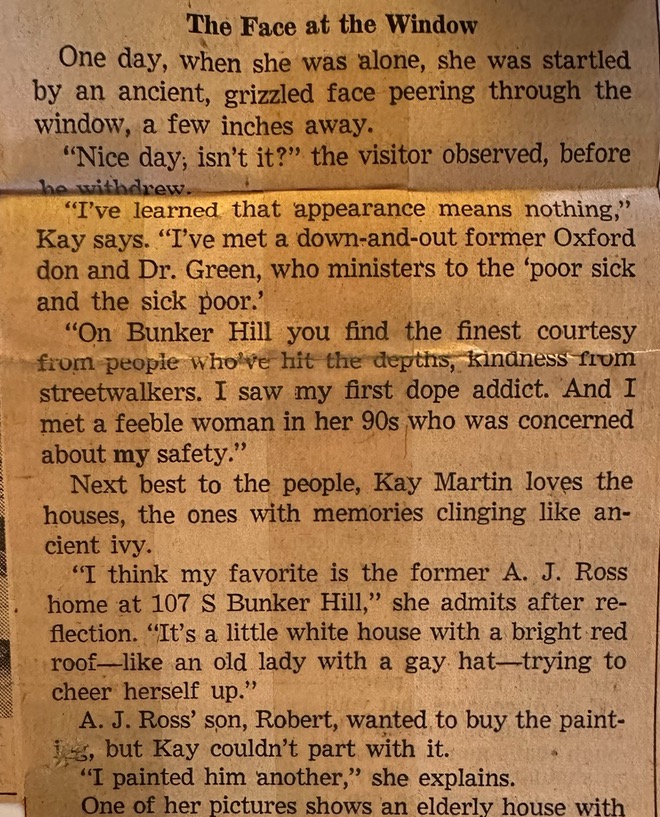

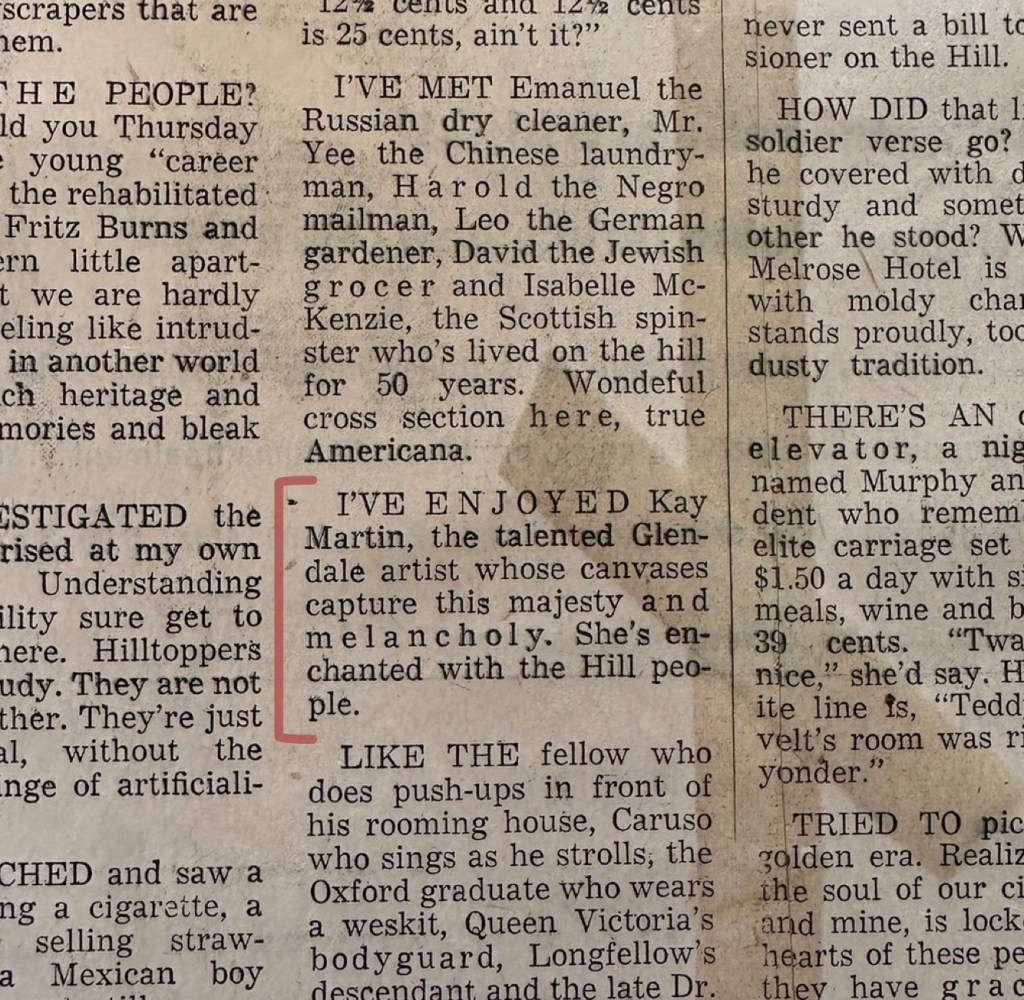

Kay had some interesting notices in the newspapers. There’s an especially charming piece about Kay in the January 15, 1958 issue of the Los Angeles Mirror, titled “Artist Discovers Tolerance on L.A.’s ‘Edge of Yesterday'” in which she describes the way visiting Bunker Hill changed her core:

Her fondness for old houses is mirrored in her proclivity toward playing dress-up, and reliving the bygone days:

IV. Later Years

With City Council’s 1959 passage of the Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project, the 1960s began with a new under-demolition Bunker Hill, one replete with the sounds of jackhammers and splintering wood, its air full of plaster dust. Kay Martin turned her attention elsewhere.

In early 1961, Martin reinvented stained glass:

In the autumn of 1962, Kay and her pal Helen Wilkes made a sketching tour through Europe; Kay sold her works at the Independent Gallery, 112 South Maryland Avenue.

Kay also turned her eye to Glendale. Here she is—

—painting 221 North Belmont, the little white wooden home where Edith Nourse invited ten friends over for an 1898 birthday tea honoring Mittie Parker; so began the Tuesday Afternoon Club (which disbanded in 1998).

After the early 1960s, there’s little about Kay and Beck. We do know that about 1964, they lost their home to Eminent Domain, ironic, since Kay’s beloved Bunker Hill went that way, too. Their house at 2084 Montecito Drive, in the Montecito Park section of Glendale, about halfway between Oakmont Country Club on the west and Descanso Gardens on the east, was lost when the 2 freeway cut through. Kay and Beck moved into a brand-new apartment complex down in the flats, at 420 North Louise, Apt# 25.

They were both in their mid-50s at this point, and presumably retired. Kay dies January 17 1978, and Beck follows the following August. While we’d expect them to be interred at Forest Lawn in their beloved Glendale, they both go back to Illinois.

And that, my friends, is the tale of Kay Martin.

V: But What Happened to Her Pictures?

At this point, fellow Bunker wonk, you are suitably frustrated by these subpar reproductions of her paintings I have shared, and wish to immediately go view the originals wherever they hang, be it in a museum or private collection, and I would say yes you must, adding I will meet you there and docent the living hell out of your experience. But, that’s not going to happen. Not today, probably not for a very long time. There’s a story here:

Kay Martin exhibited her pictures and they received great accolades, but unlike 99% of artists, she didn’t sell them. She kept the entire collection intact, because she had a very special plan for it, a vision. It was her stated intention that the entire collection be returned to Bunker Hill, to be hung in one of the “grand new hotels” destined to be built atop the new, modernized, post-redevelopment world there. Her paintings could act as a teaching aid, instructing and reminding people as to what the old, Victorian, lost world of Bunker Hill looked like.

Kay passes in 1978 and her estate is willed to sister Marjorie Reed, who lives back in Illinois. Marjorie lives another 14 years and dies in 1992, so all the paintings go to her son William E. Reed. At which point Kay’s nephew William, and wife Angela Reed, say dang, our house is now totally filled with these paintings, we need to deal with this, and more importantly we need to fulfill Kay’s wishes.

In 1994 Mickey Gustin, the Arts Planner for the Community Redevelopment Agency, starts getting letters. Like this one, saying, we want to donate this huge art collection to the CRA. The CRA, the Reeds figured, were the ones who could fulfill Kay’s wishes and place the pictures all together in one of “the new super hotels.”

The CRA says, ok, we’ll take ’em, and they’re packed up and sent back to Los Angeles whence they came. The CRA, now in possession of the pictures, requires eleven years to figure out where to display them. Apparently someone was walking through Angelus Plaza—America’s largest federally subsidized retirement community, on Bunker Hill at Third & Olive—and says wow, this place has got a lotta empty walls. And this place chock full of, you know, old people who actually like things like paintings, and who might actually remember Bunker Hill. So in 2005 Kay Martin’s pictures finally go on display up on the walls of Bunker Hill, at long last, in accordance with Kay’s wishes.

At this point, everything is copacetic: Kay’s pictures have been returned to Bunker Hill, and the old folks get to look at them wistfully, and those of us with a passion for old Bunker Hill get to visit and tour them:

Until…one day in 2014. Story goes, someone at Angelus Plaza says let’s paint the walls. AP workers take down all the pictures, paint the walls, and then realize they have to rehang the pictues…which is just more work, so you can see the problem right there. Angelus Plaza figures it’s easier just to get rid of the damn things. They call up William Estrada, in the California History Department at the Natural History Museum and say you want em? and Dr. Estrada says hey, free stuff, why not. That’s the way I heard it, anyway; I’m sure the reality is much more nuanced, certainly more complicated, or perhaps completely different.

In any event, lawyers draw up a deed of gift that irrevocably and unconditionally assigns and transfers all legal title to the paintings from Angelus Plaza to the Natural History Museum. In January 2015 a couple of guys from LA Packing at $135 an hour show up, pack the stuff, haul it off to the Natural History warehouse in Carson.

Four years go by, and I’m working on my Bunker Hill book, so throughout 2019 I would on occasion attempt to contact William Estrada, Chief Curator and Chair of the History Department, about getting an image of one of the Kay Martin pictures. I never hear from him, which is disappointing, since I’d helped Bill when NHM was restoring their 1940 WPA model of downtown, but, whatever. So in January 2020 I turn my attention to collections manager Beth Werling. We discuss getting one of the paintings shot—they hadn’t even been photographed for in-house documentation purposes—for my book. But it doesn’t happen (hence, for the book, I used one of my black-and-white images alongside color pics of Sheets and Politi). NHM’s inability to photograph a painting was due to their losing the lease on their offsite warehouse in Carson, after which the entirety of NHM’s 3D/Material Culture collections was carted off to a new warehouse in Vernon, where all remains unpacked to this day, as the warehouse slogs through the process of upgrades, and the resulting City inspections.

And that’s that: ten years in, and the Natural History Museum has yet to so much as uncrate the paintings for cataloging. In the preparation of this post, curatorial questions regarding their future were again directed to Bill Estrada, who again, remains disinterested in speaking on the subject.

I hope however I have whet your appetite for Kay Martin and her works, and will, with me, look forward to some forthcoming exhibition.

*********

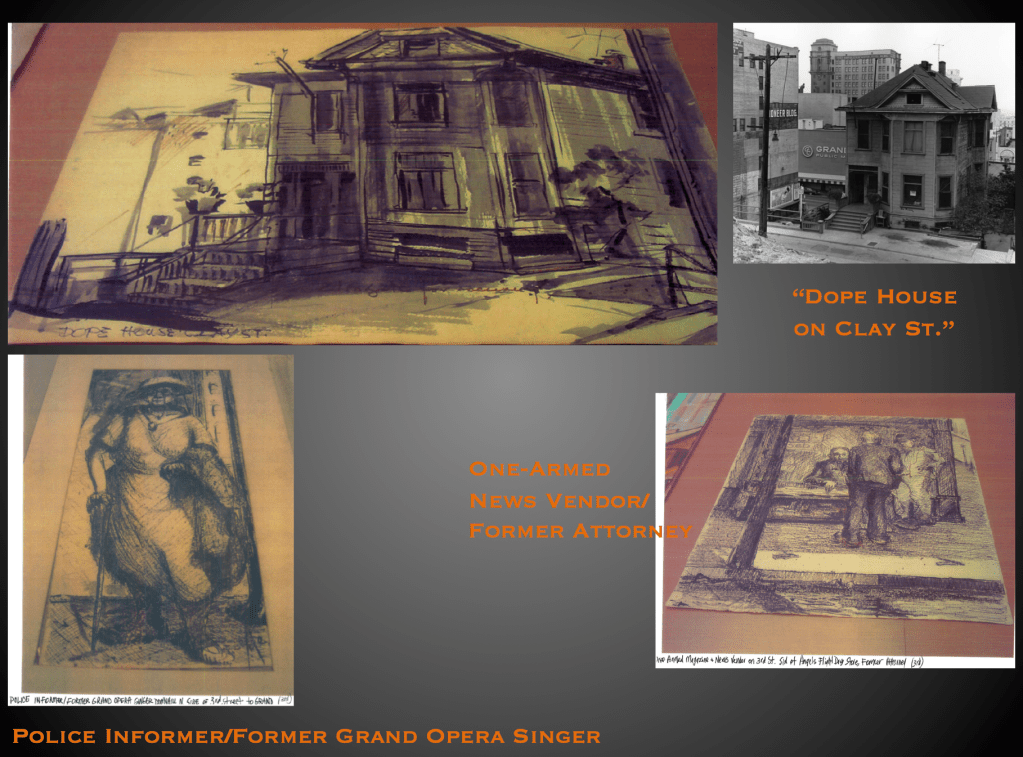

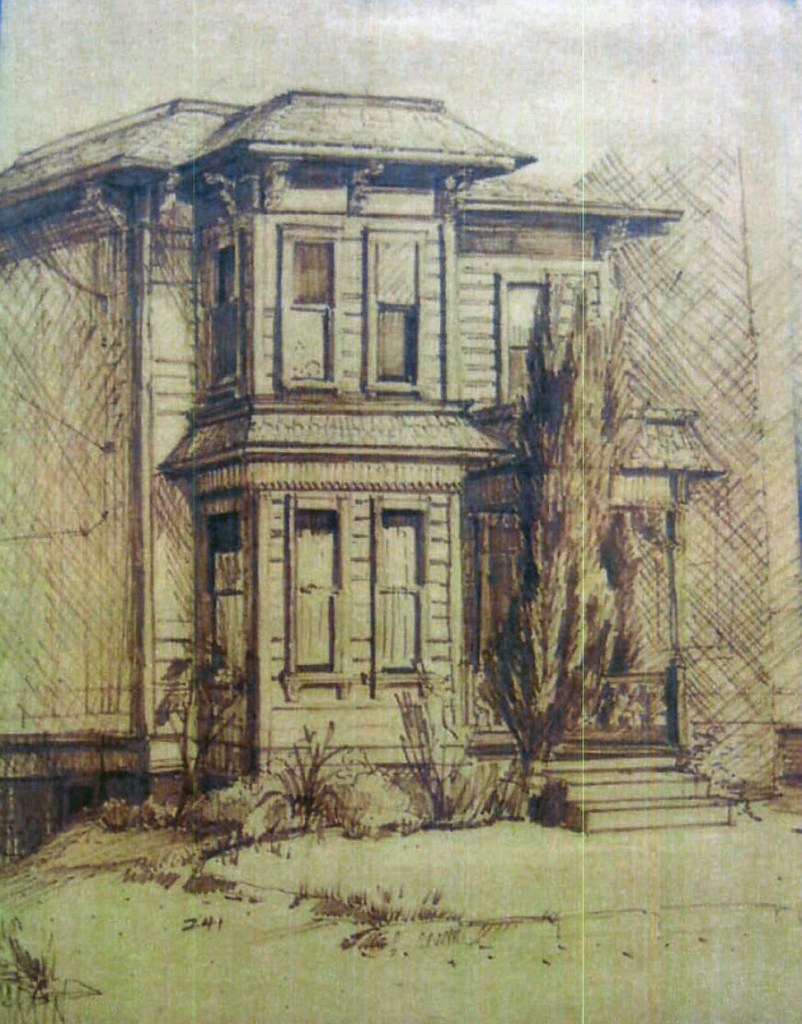

While I have you here: though there’s scant chance you’ll see Kay Martin’s paintings any time soon, I can at least share with you some of Kay’s sketches from my personal collection. Most of the work in my Kay Martin archive is from her 1962 European trip, but I do have a few nice Los Angeles examples:

*********

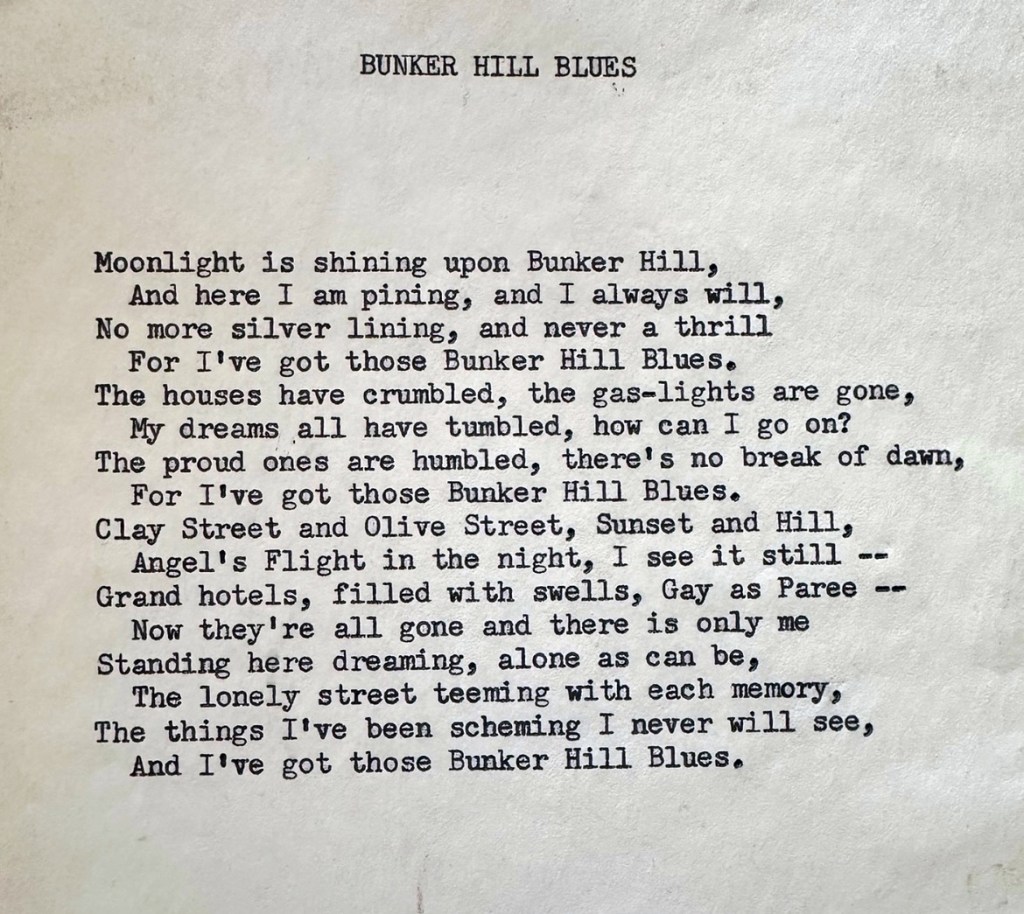

One last thing. April 11, 1958: at the Glendale Art Association’s “April Antics” held in the Tuesday Afternoon Clubhouse, Kay sang a ditty called Bunker Hill Blues. Here’s a shot of her performing it, with Association president James Alden Barber at the piano.

I’ve no idea what the music was. Judging by her garb it had a certain Gay Nineties jauntiness to it. Barber was composer, and I have his typewritten lyrics; the takeaway is neither gay nor jaunty, rather, I find the lyrics quite dark. I’m loath to call them mere lyrics—this is poetry, more to the point, the greatest poem ever written.

And so, I leave you with…the Bunker Hill Blues.

Seems appropriate for LACMA to purchase Kay’s paintings and give them a permanent exhibit.

Beautiful images of Bunker Hill. What talent Kay had! .

At least her paintings are not lost, destroyed or sitting in Goodwills across the country.

The poem is a gut-punch.

LikeLike

You’ve just told me everything I need to know about what I can expect if I happen to leave certain historic artifacts to NHMLA (which I WAS seriously considering).

By the way, ask me what happened when I contacted them ages ago asking about the 1850s oil portrait of Theresa Bay Henriot.

LikeLike

Another tour de force, Nathan, but now I’ve got “The Bunker Hill Blues.” And I won’t be satisfied until I’ve got a 1952 Ford Ranch Wagon with real wood trim.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! And ultimately frustrating. Would love to attend an exhibit of Kay’s work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The California Art Club might be interested in this story. Contact them at: http://www.californiaartclub.org

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we spoke years ago. My grandfather was the Robert Ross mentioned in this article. My sister currently has the painting that Kay painted for him. I also have a letter from her to him explaining the transaction! So nice to read about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly the most interesting historian south of Tehachapi. Now I’ve got the blues because of you rolling your barrel up and down Bunker Hill. I’m thinking 1920’s and 1930’s (when the “proud ones” abandoned the neighborhood), Jelly Roll Morton style with a slow beat: like a heart about to give up.

https://www.udio.com/songs/m4wiyZjkawV9KnjithqHHC

LikeLiked by 1 person