After Bunker Hill’s first inhabitants migrated west, the Hill became an enclave of bohemian writers, visionary artists, and vanguard spiritualists. Right? It was, after all, home to the likes of Anna May Wong, Leo Politi, and John Fante; the book Bunker Hill, Los Angeles has a whole section dedicated to its more famed denizens, including pioneering female photographers and trailblazing gay rights activists.

But let’s not forget that Bunker Hill was the refuge of Jew-hating fascists, shall we? Today we shall consider the life and times of former Hill inhabitant Ingram Hughes, head of the American Nationalist Party, who published judeophobic books, plotted to seize armories, and murder Jews en masse.

I. Ingram Hughes’ Early Life

Isaiah Ingraham Hughes Jr. was born to Isaiah Sr. (who was Ninth Illinois Cavalry, in the War Between the States) and mother Sarah Ada Abbot in Palouse, Washington, in 1875. At some point he develops his distaste for Jews, and it’s likely about that time he elects to go by a shortened-from-Ingraham “Ingram” (and abjuring Isaiah in toto, likely because it is a Hebrew name and all). He is educated at the University of Washington.

Hughes marries Nora Maude Tinsley (1869-1945) in King, Washington, in 1903. They move to San Diego in 1910, and Ingram Hughes is admitted to practice law before the State Supreme Court in 1914. Come 1920 they are separated, with Hughes (in the 1920 census as “Inghram”) living in Berkeley, and listed as a lawyer. They later reconciled and were living in Los Angeles in 1921.

There is some talk of divorce in 1928, and they separate (Maude moves with the boys to 1636 Lemoyne in Echo Park, where she lives for the rest of her days), but do not divorce until the mid-1930s. (Maude is listed as divorced in the 1940 census, and dies from stomach cancer in 1945.)

In 1932 Ingram moves to Bunker Hill:

Before we get into what Ingram Hughes did, let’s talk a bit about his home at 630 West Fourth St.

II. The LaBelle Apts., 630 West Fourth St.

Once, on the southeast corner of Fourth and Hope Streets, there were these three peas in a pod:

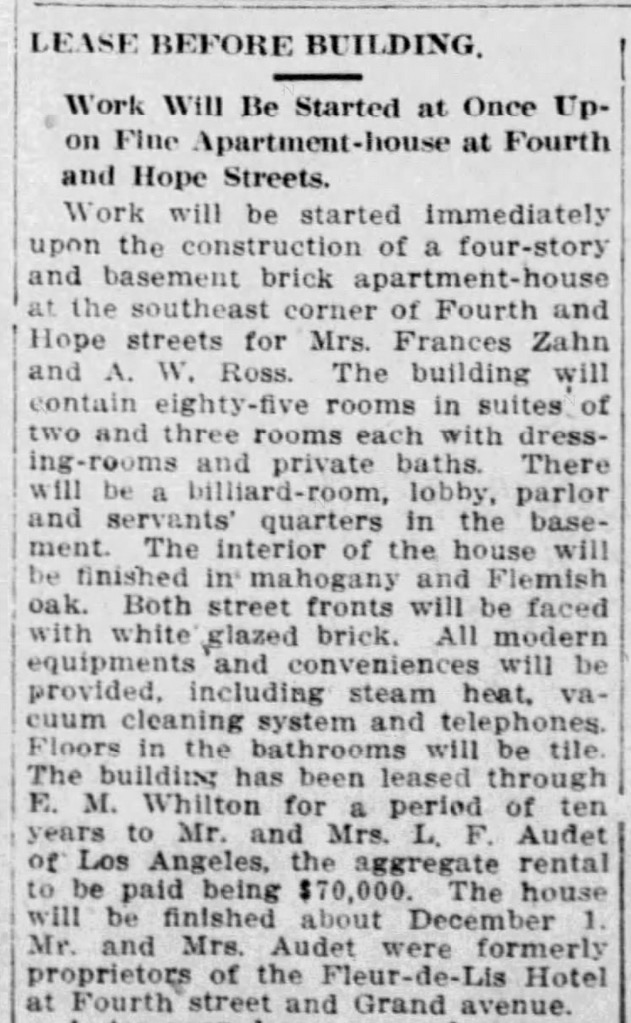

These three were all built in 1912, by Mrs. Frances Zahn and A. W. Ross. The first to go up was the Gordon, so named because it was leased by Mrs. W. C. Gordon. Then came the LaBelle:

And then, between the two, the Bronx.

Frances Zahn is also noted for having torn down the family home on Bunker Hill—a few doors south on Hope Street—and replacing it with an apartment house called the Rubaiyat. All of her buildings were designed by Frank Milton Tyler.

From the WPA drawings:

This 1941 aerial shows Hughes’ apartment house on the corner of Fourth and Hope, X marks the spot:

As long as we’re on the subject of the famous and funky folk of the Hill, here’s an annotated shot, showing some of the neighbors (Blackburn and Head lived there before Hughes’ time, but Chandler and Mather were Bunker Hill contemporaries):

III. Ingram Hughes Gets to Work

So, Ingram Hughes moves into the LaBelle at the corner of Fourth and Hope in 1932, and sets out to educate fellow goyim about the pernicious Hebrew. From the confines of his Bunker Hill apartment, he founds his own political organization, the American Nationalist Party. His intention was to expand the party nationally, under his leadership, incorporating regional leaders e.g., the Ohio/New York pamphleteer Robert Edward Edmonson.

In 1933, in his capacity as a printshop linotypist, Hughes publishes Rational Purpose in Government: Expressed in the Doctrine of the American Nationalist Party, AKA American Nationalism as Expressing the Rational Purpose in Government : Being a Declaration of the Principles of the American Nationalist Party.

In 1934 he publishes Anti-Semitism: Organized Anti-Jewish Sentiment, a World Survey. It can be read in its entirety here.

In 1935, Hughes authors and publishes this proclamation—

—calling for the holiday boycott of all Jewish-infested media. Hughes printed an untold number of these at the Los Angeles Printing Company, 1204 Stanford Ave., where he worked the linotype (LAPC printed the weekly Nazi-leaning German-language newspaper California Weckruf; shopowner Joseph Landthaler was treasurer-secretary of the local Friends of the New Germany). The flyer was distributed widely by the FNG, who ran the Aryan Bookstore in the Turnverein Hall at 1004 West Washington Blvd. (and the one at Deutsches Haus, 634 West 15th St.); it was also plastered on much of Los Angeles, and was surreptitiously inserted into copies of the Los Angeles Times in the warehouse before delivery.

From his home office in Bunker Hill’s LaBelle Apartments, Hughes corresponded with and sent literature to the likes of William Dudley Pelley, E. N. Sanctuary, Gerald Winrod, as well as European fascists like Arnold Leese and Ulrich Fleischauer.

In late 1935 Hughes planned a pogrom, involving the mass hanging of twenty Jews, including Samuel Goldwyn and Eddie Cantor. Unbeknownst to Hughes, his personal secretary, Charles Slocombe, was a spy for the Los Angeles Jewish Community Committee, and the LAJCC worked with the LAPD to bug Hughes’ Bunker Hill apartment. They decided the heavyset, balding, bespectacled, 60-year-old Hughes was more bluster than determination in such matters. Hughes was, and rightfully so, worried that Jewish spies had infiltrated—not his, of course—too many local fascist organizations, making his murderous plans too risky.

In 1936 Ingram Hughes published Ye Kynge Goethe to Towne, a Ballade of Shreddes and Patches AKA The King Goes to Town, A Metrical Romance in Ballad Form, a compendium of “pilfered, pillaged, and purloined” verse. The text was accompanied by late-Medieval woodcuts, as chosen by Ingram’s 24-year-old son Owen Rhys Hughes (1912-1994). It can be read in its entirety here.

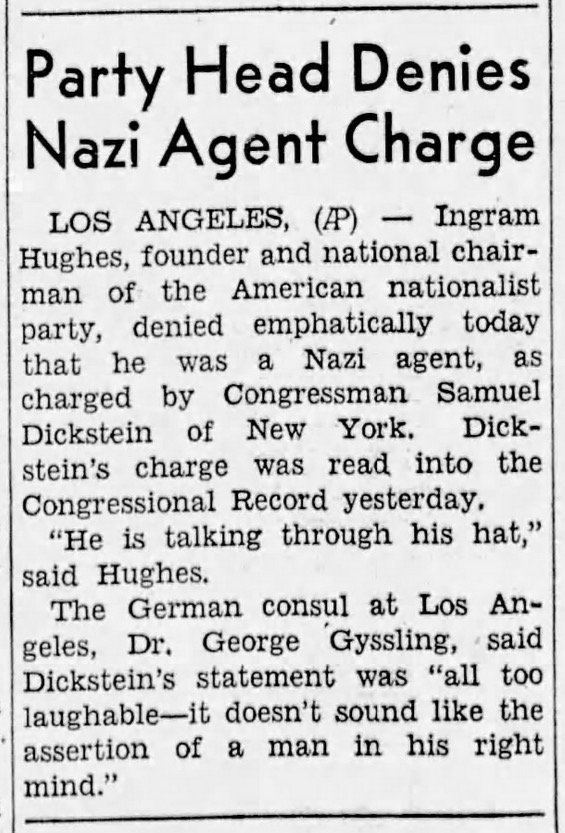

As evidenced by Ye Kynge Goethe, Hughes eventually eased up on the antisemitic screeds, preferring to simply output more anodyne, albeit conspicuously über-European, material. Nevertheless, in 1937, he was hauled before the McCormack-Dickstein Committee and grilled about his possible Nazi links:

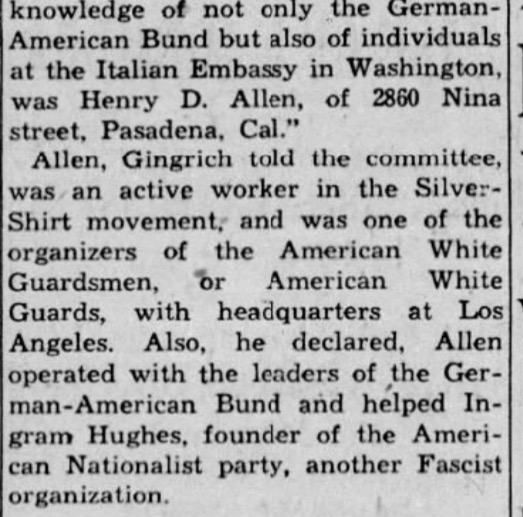

Hughes shows up again in the papers, mentioned in relation to the special House committee investigating subversive activities, in 1938:

It’s the final time Hughes is mentioned in relation to fascism. A year and change later, his Bunker Hill address is listed as that for “Ingram Hughes, Publisher of Fine Books”—

He is still listed at the Fourth Street address in 1942, according to voter rolls, as a member of the Prohibition Party:

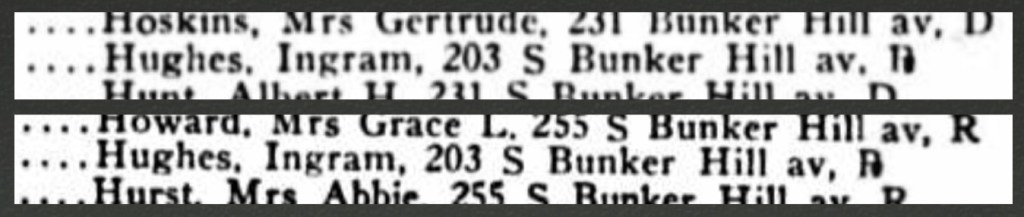

In the 1948 and ’50 voter rolls, Hughes has moved to 203 South Bunker Hill Ave.—

—and here is a shot of 203 SBHA in 1945; for all I know, that’s Hughes himself hobbling home:

And then he passes on December 27, 1949. Although he is listed in the 1950 voter rolls at 203 SBHA, his obituary places him about three miles to the southwest:

And that is the story of how, in the 1930s, Bunker Hill harbored one of Los Angeles’s fascist publishers. Of course, fascists, isolationists, and other such ilk became witheringly unpopular come 1941, with the attack on Pearl Harbor, eighty-three years ago today.

********

If you are interested in the greater story of prewar Los Angeles fascists, please see the books Hitler in Los Angeles and/or Hollywood Spies; and online, you may read Spies author Laura Rosenzweig’s thesis (Hughes is most prominently mentioned on pp. 206-240, and 280-289).

Great article Nathan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There was also another active and prominent fascist in LA called Gerald L. K. Smith. He was a friend of Governor Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin the Radio Priest before WW II. He was also active after the war. I believe he owned or leased part of a beautiful building near Pershing Square which housed a famous haberdashery on the ground floor. But I could be mistaken !

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe you’re thinking of James Oviatt, whose famed haberdashery on Olive just south of Pershing Square, was home to the Christian Defense League, which was run by Wesley Swift, a protégé of Gerald L. K. Smith. And Oviatt got into hot water for posting John Birch Society material in his shop, and sending copies of Michael Conde McGinley’s “Common Sense” broadsheet to patrons.

LikeLike

You are absolutely correct.

And I used to go to the Dean Moira 1920’s band that played there a few years ago under the aegis of Maxwell DeMille.

It was great to see the interior decor of the 1920’s Oviatt haberdashery (to the stars). Listening to the music 🎼 in that atmosphere you could drift back in time (with the help of a few “light refreshments”). The Art Deco Society has been planning a social get together at the wonderful period bar in the Biltmore. They are a great group trying to preserve historic places !

Thank you for your wonderful articles !

Jim

PS: There is a very moving performance 🎭 on You Tube of the great Irish ☘️ tenor John McCormick 🎶 singing “Little Boy Blue” at the Symphony Hall on Pershing Square in 1929. I would have liked to have been there. What a beautiful place to have such an historic performance!

LikeLike

Juedophobic? Judeo I presume unless he harboured a fear of the martial arts.

LikeLike

Ha ha yes! Fixed. The perils of not having an editor!

LikeLike