Happy Washington’s Birthday! Washington’s birthday is, of course, on the 22nd, but has, since 1971, been celebrated the third Monday of February. (Which is today, so happy Washington’s Birthday, and before you say “don’t you mean Presidents’ Day?” be advised I do not, because there is no such thing as Presidents’ Day.)

What does George Washington have to do with Bunker Hill? He never set foot in the Bunker Hill area (unlike President Hayes), and heck, George Washington wasn’t even at Massachusetts’ battle at that other Bunker Hill.

I bring up the subject because, until quite recently, there was a monumental statue of George Washington on Bunker Hill, and this being his day…

I. A Few Words about Washington

It is evident to all we should revere Washington. He led the American forces against Britain, securing victory over tyranny. He presided over the Constitutional Convention, and was the first to sign that founding document. Though elected unanimously twice, he refused to abuse his power, and stepped down after two terms. He was referred to as “The Father of Our Country” as early as 1778 and he remains known so today.

Of course, some people will discount all of this because Washington owned slaves; I suggest those people make a close reading of Winkfield Twyman’s essay on the matter, here.

II. The Houdon Washington

Our story begins with the late 18th century sculpture of Washington by Jean-Antoine Houdon.

Houdon’s Washington gained so much popularity, that many copies were made in bronze and plaster. 19th century copies include those placed at the Virginia Military Institute, St. Louis’ Lafayette Park, and the North Carolina State Capitol.

Gorham made a cast in 1909 that resulted in a number of bronze copies, including those in Springfield, Mass. (cast 1911) and at Philadephia’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (cast 1922).

Reproductions of the Houdon Washington ramped up with the 1932 bicentennial of Washington’s birth, including the statue at Valley Forge, at George Washington University, and at the Redwood Library in Newport.

III. Washington Comes to Los Angeles

Los Angeles was a bit late to the party, but began work to get a bronze Houdon Washington of its own, in 1935.

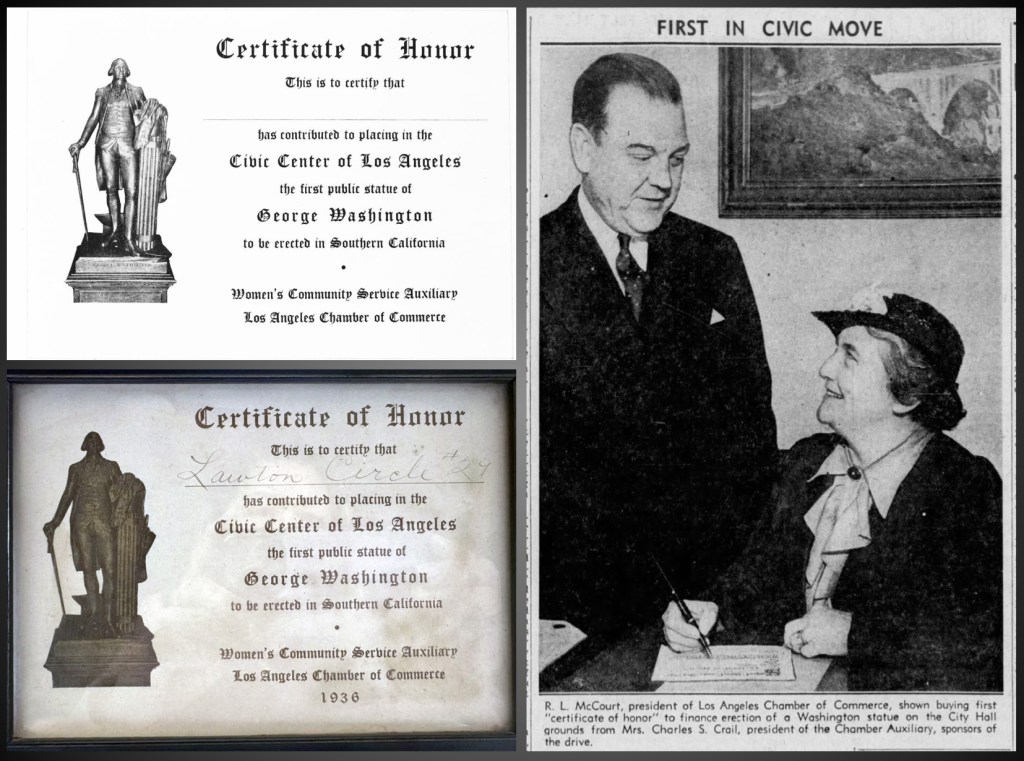

This began as an idea by Bernice Crail. Bernice (daughter of Congressman Moses Ayers McCoid, and wife of Superior Court Judge Charles Steward Crail) was, in September 1935, installed as president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce Women’s Community Service Auxiliary.

As chair of Civic Beautification, Bernice decided what Los Angeles needed was a monumental Washington statue.

Prominent women across Los Angeles (Bernice, past-president of the Ebell Club, was a mover and shaker) began a citywide movement to sell “certificates of honor” in an effort to raise funds for the statue.

Patriots and art lovers bought certificates, and in 1937 the statue was fully funded, in time for Washington’s Birthday, 1938. The ceremony was held at 10:30am, Tuesday February 22nd 1938, on the grounds of the recently-demolished courthouse. Virginia Law Hodge, State Regent-Elect, Daughters of the American Revolution, delivered the dedication address to over one thousand attendees. Speeches were made, poems were read, and the Works Progress Administration Band played patriotic songs, accompanied by the Belmont High School choir.

Note in the image above the triangular plot left-center: in June 1947 Washington was moved from the old courthouse site to that Spring Street location, near the Hall of Records entrance and directly across from City Hall —

IV. George Comes to Bunker Hill

As you are undoubtedly aware, the area of Bunker Hill north of First Street — sometimes referred to as Court Hill, given its proximity to the Courthouse (hence the former site of Court Flight) — was, once, a large hill, covered with homes and businesses. That is, until the County decided to buy all the land, kick out all the people, demolish everything (including the hill itself), and redevelop the area with a County Courthouse and Hall of Administration. Like so:

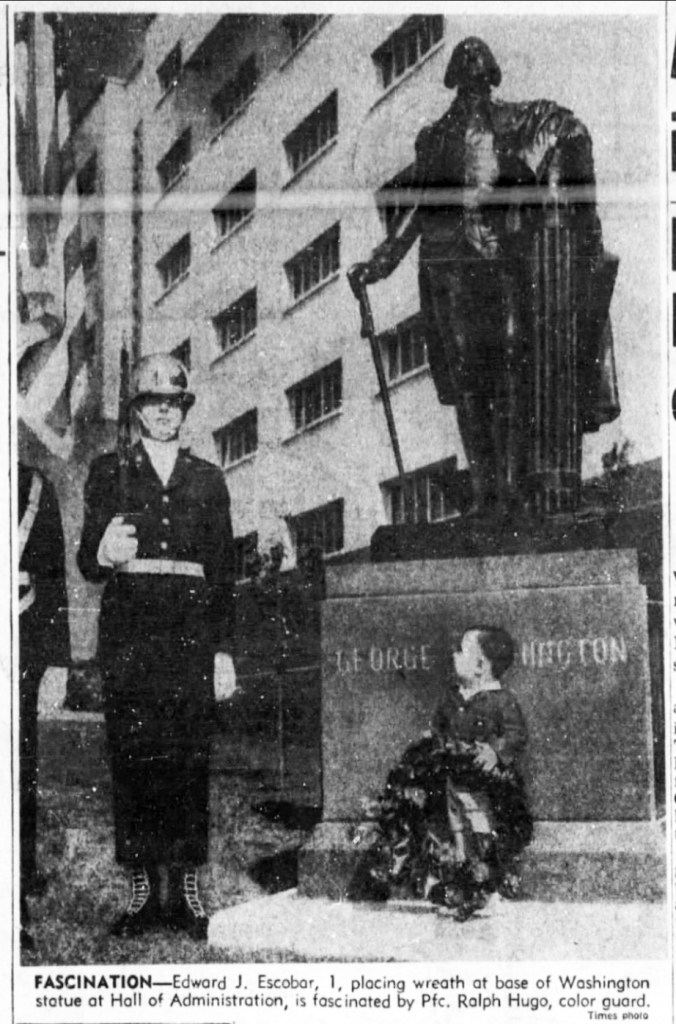

In late 1960, County Board of Supervisors member Kenneth Hahn had an idea: let’s move the Washington statue from that funny old Hall of Records building to the bright, gleaming new Hall of Administration, which had opened in October.

Washington had to be moved again, as the strip of grass on which he sat was lost to the development of the Civic Center Mall, known officially as El Paseo de Los Pobladores de Los Angeles, dedicated in May 1966.

Washington wasn’t moved far; about twenty feet west, and turned to face the park rather than Hill Street.

And there he stood for almost sixty years —

– until…

V. The Summer of 2020

You doubtlessly recall the spate of fifty-some Confederate statues removed by municipalities/toppled by protestors after Charlottesville’s 2017 Unite the Right rally, which accelerated into the removal or destruction of another 150+ monuments during the George Floyd protests post-May 2020. (For example, this, this, this, this and this.)

And some people said hold up, you start erasing history without some measure of thought first, next thing you know they’re gonna come for statues of the Founding Fathers! But, were you to query “…what’s next? They’ll come for Washington and Jefferson?” you would be roundly denounced and soundly mocked with a chorus of no-one is going to fall for your lies and divisive hyperbole! no-one is coming for statues of real Americans and no-one will! (Trump himself was taken to task for suggesting such a thing could occur.)

But they did indeed come for Washington, and Jefferson, and many more. For example:

Jefferson, Jefferson, Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, etc. (They almost got Andrew Jackson, but failed in that endeavor.)

Things did not go well either for the likes of John Sutter, the Pioneer and Pioneer Mother, the Texas Ranger, more pioneers, George Rogers Clark, Francis Scott Key, Harvey W. Scott, Lewis and Clark, Thomas Fallon, Hans Christian Heg (an abolitionist, and Union Army), a memorial to Emancipation, a monument to the Union Army, Walt Whitman, Pete Wilson, plus a beautiful and very non-racist elk.

And of course there’s the hundreds of statues, monuments, and memorials that were not removed or pulled down but “only” vandalized, like the statue of Quaker abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier, or African-American volunteer infantry regiment the 54th Massachusetts, or Tadeusz Kościuszko.

But we’re here to talk about statues of George Washington. We should note the Houdon Washington toppled in Minneapolis; the 1927 Coppini statue toppled in Portland; the 1858 Bartholomew statue of Washington defaced in Baltimore; the 1876 marble statue by the Fratelli Gianfranchi vandalized in Trenton; Stanford White’s 1891 Washington Square Arch, also hit by paint; and so on (New Orleans, Seattle), and so on.

I mention all this statue defilement to give you an idea where the cultural milieu stood in the summer of 2020 (although Washington continues to be disrespected, like the recent stories about the Houdon Washington that offended the Mayor of Chicago, and the Houdon Washington at its namesake university that spent three solid weeks as the focal point of pro-Hamas activists).

So: it’s Los Angeles, summer of 2020. We’re under stay-at-home orders and the odd curfew so as to halt the spread of the deadly COVID pandemic — your shared sacrifice will slow the virus and protect those most vulnerable! Businesses were closed. Restaurants, salons, churches, all forced to shutter. Loved ones died alone and isolated in hospitals. A trip to the store in the hope of finding toilet paper required waiting in a long line in some parking lot, a socially-distanced six feet apart from one another. Nevertheless, there was a massive upsurge in infections. Why? We don’t know, but don’t worry, we were assured it was absolutely and positively not because of stuff like this, so, go out and protest to your heart’s content.

Thus:

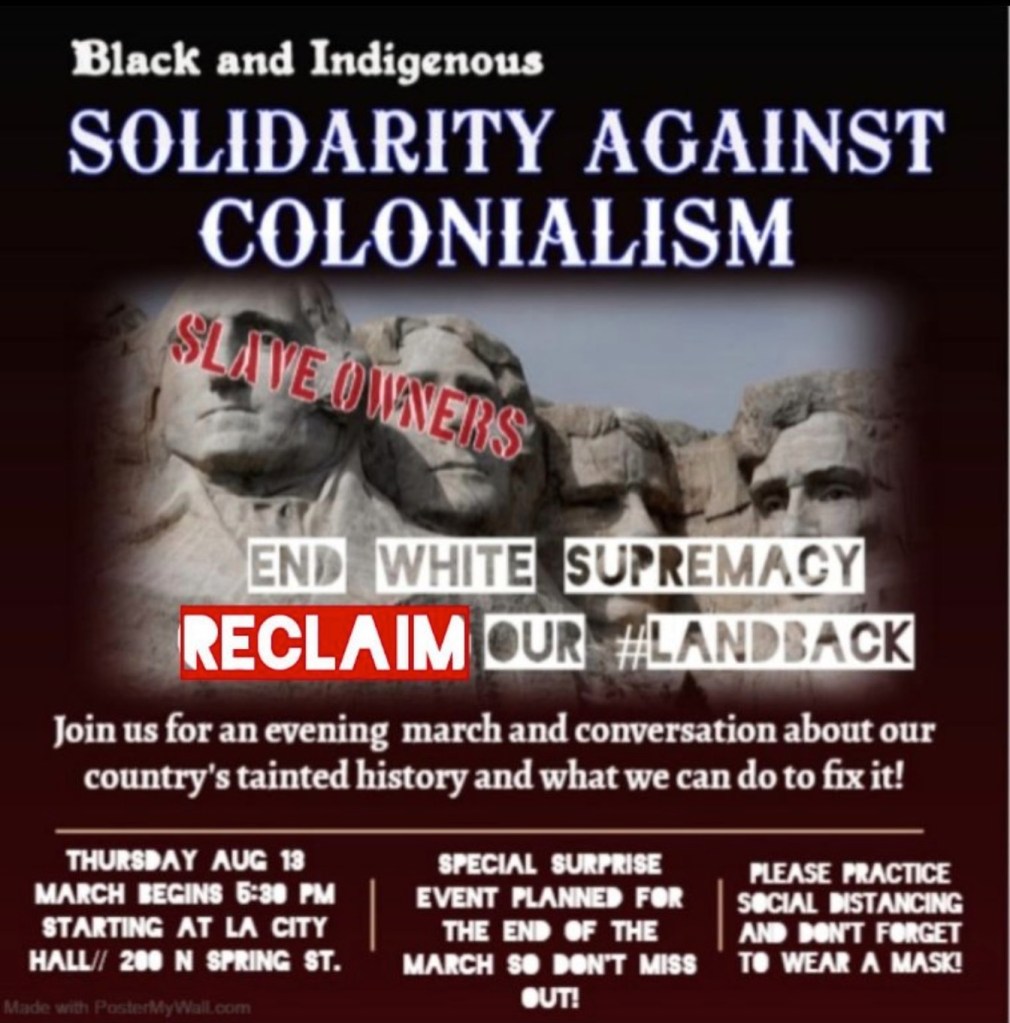

August 13th, and folks show up at City Hall to reclaim their #landback (since it was mostly white folks, I wonder if they got their land back).

And then it was on to the main event:

At 6:30, the statue was set upon by the marchers. Six individuals—Christopher Woodard, 33, of Los Angeles; Anna Asher, 28, of North Hollywood; Emma Juncosa, 23, of Los Angeles; Andrew Johnson, 22, of Glendale; Elizabeth Brookey, 19, of Burbank; and Barham Lashley, 30, of North Hollywood—pulled the statue down and spray painted it, but when they saw law enforcement ran into the bushes.

In the bushes they were busy trying to change their clothes, but were caught before they could conceal their identities and avoid detection. They were arrested, and were found to be carrying the tools of the trade—extra clothes, gas masks, laser pointers, helmets and goggles, etc.

This guy thought it was pretty funny —

Since the perps were nabbed red-handed, they paid dearly for their actions! After all, they were guilty not only of felony vandalism (California Penal Code § 594 PC) but were subject to being charged under the recently-enacted Executive Order 13933—Protecting American Monuments, Memorials, and Statues and Combating Recent Criminal Violence.

Ha ha! Got you. Did they face consequences? Of course not.

Was there so much as a finger wag? Were they given a stern talking to? Did they at least have to compose a neatly-typed five-paragraph essay titled “Why I Shouldn’t Destroy Monuments to the Father of Our Country?”

No, not in the least. Just let go, and that was that—these were, after all, the glory days of District Attorney George Gascón, who insisted it was a courageous leap toward social justice to embolden criminals, encourage lawlessness, and discomfit victims.

Therefore, the perps had all charges dropped, and didn’t even have to fork out legal fees. Emma Juncosa set up a GoFundMe to pay her lawyer and cover representation of the “Statue Six” — as ponied up by their LEO-hating comrades.

After which, the County cleaned up the statue, replaced it on its pedestal in Grand Park, and we all moved on with our lives like nothing happened, right?

Nahhhh. The County was too afraid of hurting Emma Juncosa’s feelings. (Show us where the bad statue touched you!) Instead of returning the Father of our Country to the Civic Center where it had stood for over eighty years, they hid it, in a second floor conference room at Patriotic Hall.

Don’t get me wrong, I love Patriotic Hall, and I’m glad that when people go up to said second floor conference room, they may enjoy and be inspired by Washington, surrounded by all sorts of cool GAR memorabilia.

I wanted to know more about the reasoning behind the move, so I reached out to the Los Angeles County Department of Arts and Culture to ask about the decision making process, and what went into the statue’s restoration and relocation. I got a nice, but short, email back from their Director of Communications, stating that conservation included repairing a fracture and its attachment bolts, and went on to say

After careful consideration, the LA County Department of Arts and Culture identified Bob Hope Patriotic Hall, which houses the County’s Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, as an ideal location for the statue. This location is thematically fitting for the statue of the first Commander in Chief of the United States, sitting in proximity with the various artworks and ephemera relating to military history, figures, and events housed at the Patriotic Hall.

I’m of two minds about this. On the one hand, I’m irked and saddened that we have caved to mobs of America-hating totalitarians who dictate what public statues the public can and can’t see.

On the other hand, because we allow and encourage such behavior, Washington’s statue is no longer safe among people; we can certainly expect another unhinged mob of contemptible “Statue Six” ignorami to again attempt its destruction, hence our need to remove it from view. Thus I begrudgingly admit I am glad L.A.’s Houdon Washington is now safe.

And that’s how George Washington—prominent in the Civic Center for eighty-two years, fifty-nine of those on Bunker Hill—was whisked away for fear the ludicrous-but-violent philistines shall return to finish the job, another step along the path in our charmless descent into barbarism.

*************

And that, my friends, is today’s tale for Washington’s Birthday. Yes, it’s a bit depressing. Might I suggest you now partake in some more upbeat activity, e.g., go internet-visit Mount Vernon, read Washington’s farewell address, and make yourself a cherry pie or some Washington Cake.

I had wondered where it ended up. It still angers me that it’s not on display.

Another long lost tribute to Washington is Radio Hill, which for a short time was made a park in his honor.

LikeLiked by 1 person