So you’re flipping through your copy of Los Angeles Before the Freeways and thinking well, that’s a great old building, I wonder what’s there now?

So, just for fun (if your idea of fun is a hefty dose of hiraeth) here are ten shots from Freeways, paired with a contemporary view:

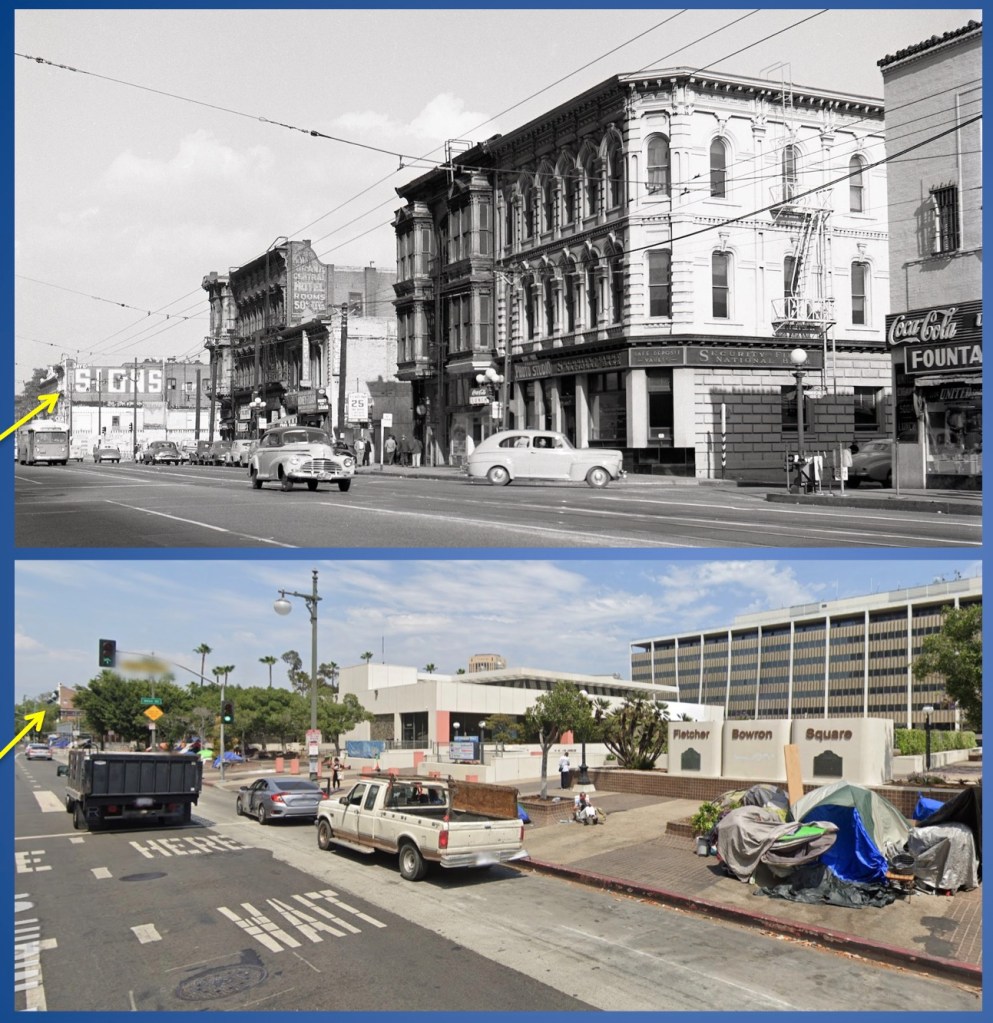

ABOVE: Looking north on Main; most prominent is the Ducommon Block (Ezra Kysor, 1874) at Commercial Street. Security First demolished the structure in mid-1951 and replaced it with a modernist bank building by Austin, Field & Fry. That building was demolished in mid-1970, as was this stretch of Commercial Street, wiped away for the Los Angeles Mall. The Mall, best known for its Triforium, was designed by Stanton & Stockwell in 1968 and opened in December 1975.

The torn awning indicates Jerry’s Joynt (home of the world-famous Jade Lounge) — see views toward it by clicking here and here — now wiped away by a freeway entrance. Look closely and you can see how the south end of the Garnier Block was removed for freeway construction.

Looking at the northeast corner of Main and Market streets; the Amestoy Block (Adolph Charles Lutgens, 1888) was made a parking lot by the city in late 1958. Market Street was then wiped away in favor of Stanton and Stockwell’s City Hall East (1972).

Behold the Robarts Block (John Hall, 1888) at the corner of Seventh and Main, in 1950. It was demolished in 1958. Note how its neighbor the Cecil has reworked its sign from “$1.50 Monthly” to “Low Daily.” This is of course the signage that existed for decades before nogoodnik Matthew Baron painted it over.

Center, the 1888 Cohen Block, 334 South Spring. At left, a bit of the Willard Block (Carroll Herkimer Brown, 1893). Both made into a parking lot, 1961. Note a corner of the Ronald Reagan State Office Building (Welton Becket + Associates, 1991) where the Willard Block once stood.

213-221 South Spring Street. At right, the Polaski Block (Abram Edelman, 1895); at center, the Brode Block (Robert Brown Young, 1891); and at far left a Romanesque Revival commercial structure (architect unknown, 1889). Image shot in 1954; the Times-Mirror Company demolished the buildings for surface parking in early 1956, eventually building this parking garage in 1988. Note the Tony Sheets bas relief. The structure was designed by Conrad Associates, who are best known for its 1975 World Trade Center at 350 South Figueroa — which ALSO has monumental Tony Sheets bas reliefs.

The Bath Block (Robert Brown Young, 1898), at the southeast corner of Fifth and Hill streets, was developed by Albert Leander Bath, vice president of the Stowell Cement Pipe Company. The structure, with its nifty Venetian Gothic ogee arches, lasted all the way through the spring of 1980.

At far right, the eight-story Merchants Bank and Trust (Dennis & Farwell, 1905) with the “Water & Power” neon still stands today, though it was reclad with a modern façade in 1968, designed by William Hirsch Architects + Associates. At left, note the towering Million Dollar Theater down Broadway. Between the two, we’ve lost the Romanesque-facaded Potomac Block (Curlett & Eisen, 1890), demolished for surface parking in 1953, and Bicknell Block (Morgan & Walls, 1892), demolished for surface parking in 1958. Both the Boston Dry Goods building (Eisen & Hunt, 1895), and the Newmark Block, (Abram Edelman, 1898) — the two structures seen at left in this image — are still with us, sort of, having been cut down to one story and fitted with new fronts.

For a site called “BunkerHillLosAngeles” this post hasn’t had much Bunker Hill in it, so, here y’all are! At left, the gleaming-white Black Building (as seen in the book Bunker Hill, Los Angeles on page 133), a 1913 office building by Edelman & Barnett, for George and Julius Black, at 361 South Hill Street. Across Hill, the late-Victorian Strong Block (also known as the Stanford Hotel and the Brighton Hotel), Frederick Rice Dorn, 1895. Further on is the backside of the Grant Block (seen here with painted signage Grant Building), at Fourth and Broadway, which looked like this; it was originally a three-story structure (Frank Sawyer van Trees, 1898) until enlarged with four more stories (John Parkinson, 1902).

The Stimson Block was an outrageously important structure, designed in skyscraper-meets-Romanesque by Carroll Herkimer Brown in 1892. The man who built it, Thomas Douglas Stimson, used Brown to build an incredible Romanesque Revival house, which you likely know. Downtown’s Stimson Block was demolished in 1963, just because. It’s remained a surface lot these past sixty+ years.

Oh, one last thing about the Stimson Block, that neon sign in the Hylen image at left? Take a close look at the modern image on the right, on the wall of the building across Harlem Place. There it is:

(Before 1958, Paraiso had been at 400 W Sunset, in what became the space for La Colima)

If you liked these ten old images of vanished downtown, be sure to pick up a copy of the book—it has another 130!

If this post does well, I’ll do another; shoot me a note (see “contact” at upper right of this page) with the building of which you most want to see a then-n-now!

hi, i was wondering where you got the archival images for this blog post? i’m working on a historical write up about the 1950s for the metro transportation research library and archive and i want to write about what aspects of los angeles were destroyed to become parking lots and freeways 🙂 thank you so much !

LikeLike