Greetings! Though this is a Bunker Hill blog, I will on occasion cover tangentially-related subjects (like Chavez Ravine or Cooper Donuts, or even Disneyland), especially if there’s debunking to be done. Today’s debunking, though, is altogether unrelated to Bunker Hill. After being told for the millionth time that Roger Rabbit is a documentary, I’m finally giving in to my overpowering, long-fermented urge to douse the fervid, fervent flames of the “Los Angeles Streetcar Conspiracy” narrative.

*****

Los Angeles has a dark and hidden history, and here’s part of it you should know: we once had the largest, best run, most efficient, most beloved, most profitable, publicly owned streetcar system in the world. The Red Cars! But! The bloated plutocrats and greasy oligarchs said NO! Profits over people! A cackling cabal of big oil, big tire, and big auto conspired to buy up all the Red Cars and destroy them! Which they did! Then they needlessly replaced them with horrible nasty busses which people disliked so much they all went out and bought cars! And that, my friend, is the reason we now live in a dystopic autopian hellscape of traffic and smog and sprawl.

Not only that, but it was such a grand and shameless conspiracy, that Standard Oil and General Motors and Firestone Tire actually got taken to court and were found guilty of conspiracy and had to pay huge fines! But the damage had already been done to the poor beloved streetcars. All of America’s streetcars had been tossed in the sea by General Motors, and the corporate fatcats puffed contentedly on their cigars and just laughed.

Of course, none of that is true. “But Nathan,” you say, “the GM Streetcar Conspiracy is a real thing! Literally everybody knows about it!” Sorry to burst your bubble but no, the entire tale is twaddle and hogwash. Not even, like, there was a conspiracy but it wasn’t that bad. I’m saying no, it’s literally not a thing that ever existed. Don’t believe me? Read on!

***

Every time someone says “big auto and big oil ripped out the efficient streetcar in a freeway-building conspiracy, you know” they give you this look like “and now I’ve imparted to you secret knowledge they don’t want you to know, for it is the dark suppressed history of LA, be careful with knowledge so powerfully arcane” even though it was the plot of a movie that made $350 million and won three Oscars.

Seriously, during my 30+ years in Los Angeles I haven’t gone three weeks without someone saying “Who Framed Roger Rabbit, that’s a true story, you know!” If you don’t know the story, Roger Rabbit‘s premise is that Judge Doom — who looks so cartoonishly evil he makes the Indiana Jones Nazi meltingfaceguy look like Mister Rogers — has a plan to force people onto the roads, wherein he buys up the streetcars to destroy them and build freeways:

But none of that happened (it being, after all, a movie about people interacting with cartoons) but the event it’s purportedly based on did not, in fact, occur. The streetcar: not beloved, not efficient, not a public utility, not profitable, and most of all, not the victim of — or even involved in — a conspiracy in any way, shape, or form.

At this point pearl-clutchers exclaim “oh Nathan how dare you! You just hate rail! You obviously despise trolleys, and rail travel, and the people who use it!” Hey, do you know what I do all day when I’m not writing essays like this for you? I operate a railway. If I could go back and time and do one thing it would be ride the trolley around downtown and then out through some orange groves. But people like to mythologize and fetishize that which has been lost to time (e.g., Chavez Ravine; I cover that phenomenon a bit in the first three paragraphs of this) and to be honest I don’t blame them. I’ve been guilty of that too, a billion times, over the course of my life. But as a historian we must side with facts over anemoia and hiraeth. In any event, here we go…

*****

I will spare you the complicated early history of the streetcar in Los Angeles, and how it was formed, but what you basically need to know is that there were, in twentieth-century Los Angeles, two main streetcar networks, the Pacific Electric, and the Los Angeles Railway:

The Pacific Electric (PE), whose red-painted cars thus dubbed it the Red Car, was the larger and faster of the two, and was more interurban than intraurban, taking people out to Pasadena, Long Beach, Santa Ana, and the like. The Los Angeles Railway (LARy) had yellow-painted cars, hence its common name The Yellow Cars; its lines were concentrated around downtown, but branched out into some suburbs. (Disclaimer: I am far from an authority on streetcars, and I know juicefans [known for loving that sweet, trolley-powering electric current] are understandably fetishistic when it comes to the topic. I am quite certain I will say something to annoy you [“he didn’t even mention that PE ran standard gauge and LARy was narrow gauge!”] so let me apologize in advance. Trust me, I get it. You can only imagine how I feel when people say Angels Flight is “Victorian.”)

The Pacific Electric Red Car, in brief: Henry Huntington began the Red Car in 1901. He didn’t do so to earn money from fares, or to make a great navigable city; it was just a tool to get people out to his new subdivisions.

After having done so, it could have been Hungtington’s right and due to simply dismantle the whole shebang; it was his property, after all. Instead, in 1910 he sold PE to Southern Pacific Railroad, who made it a subsidiary. Pacific Electric Red Cars reached peak ridership in the mid-1920s and began its decline, and though streetcars were losing money, Southern Pacific kept it so they could run freight on the tracks. Busses, though, were the future — in 1923 Pacific Electric began a joint bus venture with Los Angeles Railway called Los Angeles Bus Lines, to connect rail lines and expand service. Pacific Electric began switching their Red Cars to busses in 1925. In 1936 Pacific Electric bought an entire bus company, the Motor City Lines, to facilitate the switch to busses.

And the Los Angeles Railway Yellow Car: not started by Huntington, but he did purchase it in 1898. Same deal: ridership declined, and LARy began converting to busses in 1930. The Huntington estate sold the entity, in 1944, to National City Lines. They renamed Los Angeles Electric Railway to Los Angeles Transit Lines, but the yellow cars remained the Yellow Car. (If there are times I refer to the LARy post-1944, and you’re tempted to exclaim “but it was called LATL then!”, please accept my apologies in advance.)

*****

Now you know the two main streetcar players, and — before we get into the conspiracy weeds — here are some building block truths about streetcars: they were not a public utility, they didn’t make money, they were in fact not efficient, and people didn’t care for them much, and their being replaced by busses was a simple natural progression.

Four reasons the owners didn’t like streetcars:

Government price regulation. Despite being privately-owned, government regulators forbade streetcar owners from engaging in European-style zone pricing. That is, if you hop on the streetcar for five cents, you could ride as long as you wanted, as far as you wanted. Even when wartime inflation eroded that five cents to half its value, local government forced the PE and LARy to maintain the fare. (Turns out that much of Los Angeles’s much-derided sprawl has less to do with the oft-blamed automobile, but is because of the streetcar system, in that because of a lack of zone pricing, it was just as cheap to trolleyride to and from your suburb as it was to live near the city center.)

Government road upkeep regulation. The Los Angeles Public Utilities Board, besides prohibiting necessary price increases (despite the streetcars not being a public utility, but that’s your local government at work), also caused the streetcar companies to bleed money in that they charged them for pavement upkeep on the adjacent roads — pavement the railcar companies didn’t even use. Local bureaucrats literally forced streetcar owners to subsidize their competition, including jitneys, which were primitive road-using busses that poached waiting streetcar customers.

The unions. Trolleys were labor-intensive, as opposed to busses: there were two crewmembers on each trolley, the motorman and the conductor, as opposed to a lone bus driver. Labor unions were forcing streetcar companies to pay above-market wages, which is why the companies cut so many positions, leading, again, to busses. Ergo, many cars were converted (at some expense) to one-man crews in the late 1930s, but streetcar wages being above market still stung operators.

Forced service. Local government required streetcars to provide service on all the routes they owned, and thus forcing them to run on unprofitable lines. Naturally they turned to busses, which are cheaper to operate, and allowed them to revamp the lines.

Moreover, streetcars required expensive, dedicated rails, rails which required ten times the engineering time and expense of bus lines. And if a streetcar breaks down, that line is down until the trolleycar is removed/repaired/restored. If travel patterns change, the rail stays there (and again, the government forced owners to run your streetcars on every rail, even in the face of financial loss).

Conversely, busses cost less, carry more passengers, and could change routes with ease. No wire, no tracks, no catenaries, no electrical power plants, and no private rights-of-way to maintain.

But let’s not forget, people didn’t like streetcars, or at least not as much as we’re led to believe. At the peak of ridership in the early-mid 1920s, people were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with overcrowded streetcars, poor service, and slow gait. This led to the voters passing the Major Street Traffic Plan of 1924, which allocated city money to widen and improve streets, allowing more people to have cars (which had recently become within the buying power of the working man) and thus an alternative to streetcars. Streetcars were noisy, slow, uncomfortable, and had no air conditioning (yes you could roll down a window, but busses had actual AC) and so it’s no wonder people were abandoning them. Sure, there was an uptick in streetcar ridership during the WWII gas rationing/tire rationing era, but post-1945, hot damn did people want the freedom and comfort of their own Plymouth.

*****

And now we address the whole “conspiracy” part of our program. But before I do, just as an introductory aside, do you know who was, historically, all hot n’ bothered to destroy streetcars? Progressives. “Traction ring magnates” were considered as evil as the “railroad octopus” and Progressives considered the private streetcar entities to be capitalistic kleptocrats, remnants of the Gilded Age to be destroyed (The Nation magazine, for example, was not a friend of mass transit). And long before you had National “Streetcar Conspiracy!” City Lines in the picture, Franklin Roosevelt and his Works Progress Administration — closest thing we ever got to socialism in America — looooved tearing out streetcars: FDR’s WPA was crucial to subsidized road building, and began ripping up streetcar tracks all over America. And let’s not forget progressive New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who in the 1930s worked tirelessly to dismantle the city’s streetcar system: “bus operation in place of trolleys is not only a boon to the citizenry of New York in that it provides faster, more flexible and more comfortable transportation, it also reduces noise, keeps traffic moving faster, and eliminates the danger of wet rails…” said the man himself. Anyway. Just something to remember when you’re pitching stones at those evil streetcar foes.

The Conspiracy. The story goes, there was a company called National City Lines. They were a “front” for big oil/tire/auto. They conspired to destroy the streetcars, which they did, but got caught, and were found guilty. And…scene.

National City Lines is formed in 1936 and — hold up: first, a quick and important sidenote about the PE Red Cars: So, National City Lines bought the LARy Yellow Cars (we’ll get to that). So why is the common narrative always about the Red Car? That’s largely due to Roger Rabbit —

— thus the Red Car is remembered than the yellow-garbed LARy system, so when the “conspiracy” is discussed these days, the tale invariably involves “the Red Car.”

Ladies and gentlemen, If you take one thing away from this entire post, have it be this: National City Lines (ergo by extension General Motors & their fiendish oil-pumping, tire-peddling friends) never touched one single Red Car in any way, shape, or form. Not one. NCL didn’t so much as look askance at a Red Car. So what was the conspiracy that destroyed the Red Car? Sorry to burst your bubble, but there was none. Southern Pacific, PE’s parent company, began abandoning rail service in large swaths because it was prudent to do so, and running streetcars was not part of their business plan in the first place. Eventually, come 1953, SP sold the works to Metropolitan Coach Lines, which was run by old Pacific Electric guys (particularly Jesse Haugh, a former PE executive) and these PE guys converted much of their rail transit to bus service (click here and here). Red Car’s nail in the coffin, though: Metropolitan Coach Lines/the Red Car was subsequently acquired by the government. In 1958 the (taxpayer-funded) Metropolitan Transit Authority, in league with the California Public Utilities Commission, took over and killed the Red Car. It was the California Public Utilities Commission — whose commissioners were appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the State Senate — who officially pulled the plug on the Red Car. Please never forget that, and don’t forget to to tell it to the next person (perhaps one of the 70,000 who “liked” this typical and falsehood-packed post) who says “big oil killed the Red Car.”

Anyway, back to the reason you’re here today: You have been told that National City Lines, who was really General Motors, bought the streetcar system, and killed it to replace it with busses and autos, and there was a trial, and they were convicted. Big Auto was convicted, you will be told, of conspiring (in Judge Doom-like fashion) with Big Oil and Big Rubber to destroy the streetcar. And that’s why America no longer ha streetcars.

Except that’s all hooey, the lot of it:

National City Lines is formed in 1936. In 1939 the president of NCL approached — not General Motors — but a company called Yellow Truck & Coach Manufacturing, for financial assistance. The money NCL got from Yellow Truck — Yellow Truck being a subsidiary of GM — meant that money came a requirements contract. Standard stuff, and altogether legal: it said that NCL needed to use GM’s money to not go and purchase equipment from competing companies. That’s it. People have dug into NCL’s records and GM’s records from here to Timbuktu and there is zero evidence that GM held sway over National’s management; no evidence of managerial control, nor did they have any say regarding National’s movement from streetcars to busses.

In 1945, National City Lines bought the LARy Yellow Cars. NCL bought a lot of lines in the United States, about 10% of the lines in the country. In some areas NCL began to convert to busses, and in other areas they actually expanded electric rail. But all we hear about is their conspiracy to destroy all of America’s rail.

Before I get into the particulars of why that’s not true, let me state something nobody ever mentions: there were 600 major metropolitan areas in America with streetcars. National City Lines got their hands on about 60 of them, so, again, only ten percent of America’s rail is thus tainted by some sort of “streetcar conspiracy.” If it required a conspiracy involving General Motors and Standard Oil to demolish those 60 rail centers, what happened to the other 540? Seriously, tell me. 540 urban areas had streetcars, and they ripped out their streetcars. Without the involvement of National City Lines, without being tainted by a nefarious streetcar conspiracy. (Yes, I’ve been on the old trolleys in New Orleans, San Francisco and Boston, and yes, I’m aware that there are some places like Pittsburgh and Philadelphia that run modern light rail on their old streetcar-dedicated right-of-ways; so subtract those and a few others and tell me why the other 530 or so major American urban streetcar areas abandoned their streetcars without the input of National City Lines.)

So: was National City Lines brought up on charges of conspiracy to destroy streetcars? No, they were not. Defendant National City Lines — and by extension the old bugaboos of GM, Standard Oil and Firestone Rubber, via Yellow Truck & Coach — were brought up on two counts:

Count One: Violating Section One of the Sherman Antitrust Act (the SAA is Gilded Age legislation that prohibits monopolies; it famously broke up Standard Oil. Read more about it here). NCL were accused of trying to secure control of transit-providing companies, which they were not trying to do, ergo, they were acquitted. As in, found not guilty and absolved of wrongdoing regarding accusations of restraint of trade. Got it? Ok.

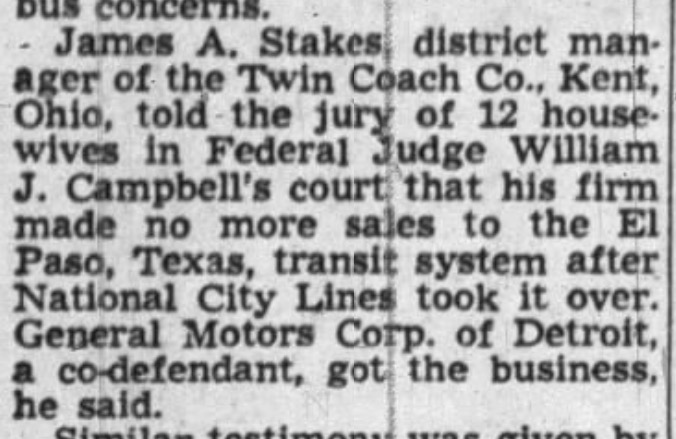

Count Two: Violating Section Two of the Sherman Antitrust Act. They were accused and found guilty (upheld in appellate court, U.S. v. National City Lines, 186 F.2d 562 [7th Cir. 1951]) of selling busses to themselves. Literally nothing to do with streetcars. When NCL was laying out new bus lines, they committed the “crime” of using their own busses. For example, who were some of the witnesses for the prosecution? Pacific Ford Motor Coach, and Twin Coach Company, who testified that they lost out on business when NCL (who, again, had a tying agreement with GM) bought GM busses. But Pacific Ford and Twin Coach said that just wasn’t fair. The government thus brought NCL up on charges, because being your own customer is illegal under antitrust law.

So the jury said awwww and found GM guilty of selling itself its own busses.

Let me sketch a rough analogy for you. Let’s say you had a restaurant — you open a vegetarian restaurant, and you have a plot of land out back so you grow your own vegetables. Farm to table kinda thing. But the government comes in and says you can’t feed people your own vegetables, because that’s not fair to your competition. You have to buy your vegetables from your competitor (and tough luck if those vegetables when not as tasty and more expensive). You can’t use the ones you grew yourself, but must buy someone else’s, because that’s fair.

NCL was fined $5,000. “That’s an outrage!” screeches literally everyone, “they got a slap on the wrist for conspiring to destroy the streetcar!” First of all, again, the accusation and judgement had absolutely nothing to do with streetcars, but point being, $5,000 was the absolute maximum fine they could get for selling busses to themselves. The government set that fine long before the trial began; it wasn’t a slap on the wrist imposed by some pro-Big Oil judge, or whatever conspiracy theory you have.

I feel like this cannot be stated often enough: In the court’s opinion, there were, certainly, damaged parties — competing bus manufacturers. But there was never a mention of electric railways.

And again, there were hundreds upon hundreds of cities who never had a smidgen of GM/NCL influence, and they dismantled their streetcar systems just fine on their own (American cities, heck: the UK, Japan, and countless other nations have but a fraction of their original tram systems, and GM/NCL wasn’t there, either).

So, after National City Lines was convicted of the very non-streetcar-related crime of selling busses to itself in 1949, you’d think that would be the end of the story, right?

Nooooo.

*****

Enter Bradford Snell. It’s 1974, here comes Snell, he’s an antitrust attorney from San Francisco. Snell had been bankrolled by the leftist Stern Fund to write a paper about how General Motors was eeeevil, and had destroyed America’s streetcars. This was the genesis of the streetcar myth. Snell became a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly and there testified to the Senate that Pacific Electric was forced by National City Lines to convert to busses and then, because people would be so horrified by the busses, they’d buy automobiles. Yep.

Seriously, that was actually his argument—here is a direct quote from Snell, that Pacific Electric’s plan was “to convert its electric street cars to motor busses — slow, cramped, foul-smelling vehicles whose inferior performance invariably led riders to purchase automobiles.”

Let that sink in: Snell said National City Lines forced PACIFIC ELECTRIC to do this. As you know, NCL never had any dealings with PE. Ergo, Snell is an idiot, a liar, or both. (Spoiler alert: it’s both.)

Snell’s argument also hinged on the “truth” that busses were inferior to streetcars. Of course busses were more flexible, easier to run, cheaper to run, and actually profitable. (But hey, this is government! They don’t care about the owners of things.) What about the ridership? Well the streetcar was louder, slower, it jerked you about on less comfortable seats compared to the cushy bench seats of 1950s busses (yes, I am aware that many streetcars had upgraded from wooden to upholstered, but still), there was heating and air-conditioning, etc.

Most importantly, Snell testified to the Senate that back in 1950 GM had been convicted of a “criminal conspiracy to monopolize ground transportation” — which, of course, they hadn’t. Like saying NCL worked to destroy Pacific Electric…was he consciously lying, or just making stuff up with all the best intentions? Oh wait, it’s the same thing.

Anyway, there were hearings about this through 1974. They made the news largely because San Francisco mayor Joseph Alioto testified to the Senate that GM was “a monopoly evil” and LA mayor Tom Bradley (quite incorrectly) testified “GM scrapped the Pacific Electric” — of course, it turned out SF and LA both had lawsuits against GM and Alioto and Bradley had financial interests in screwing GM, so naturally they lied to the Senate. Yay!

Then in 1987 60 Minutes picked up the tale and said our streetcars were “murdered by conspiracy.” It’s absolute trash, but it’s a fun watch for the vintage streetcar clips. Between the 60 Minutes piece and Roger Rabbit, every Gen X’r in the world ardently argues the conspiracy narrative.

******

And now to wrap up. We know that natural forces sickened the Red Car until your local government pulled its plug. But what of the Yellow Car? If General Motors didn’t rape and murder it, as you’re so constantly told, what happened to it, exactly?

So LARy is bought by National City Lines. The Yellow Cars are largely converted to busses through the 1950s — (and before you say yeah! evil GM busses! they actually replaced most streetcars with ACF/Brill electric trolleybusses) until by 1958 only five (of the original 25) streetcar lines remained in operation — the J, P, R, S and V. These were sold to the Metropolitan Transit Authority (today LA Metro). Just as a public agency had destroyed the whole of Pacific Electric Red Cars, it was a public agency that destroyed the last of the LARy Yellow Cars. Between 1958 and 1963 it was your tax dollars (well, your grandparents’ tax dollars) that sent all those Yellow Cars to the National Metal and Steel Corporation junkyard at Terminal Island, where they were broken up for scrap.

*****

Let me reiterate, I love rail. I would have loved riding the streetcars (I love riding them in Perris) just as I love running an Edwardian-era electric train in downtown Los Angeles, so, count me among the juicefans. Plus, L.A. streetcars began with a Bunker Hill connection — in that the first line, the Sixth & Spring line, was founded in 1874 by Judge Widney, who resided on Hill near Fourth.

That said, I’m not going to allow you to believe things that aren’t true. Also, you’re not allowed to complain about losing our old streetcar system if you’re not willing to ride the 114 miles of rail transit we currently have in Los Angeles (including, I might add, the longest light rail line in the world). That’s right, even after destroying the streetcar, Los Angeles still has the largest light rail system in the United States.

*****

Oh, one other thing: if you raise an eyebrow at my use of “busses” rather than the more traditional “buses” that’s because one of the objects in my greater “old LA” collection is this —

— and if that says busses, then, so be it!

Interesting shot of a pair of Southern Pacific drop-bottom gondolas, class G-50-22. The actuator rod is visib

LikeLike

As much as I love “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”, it is a work of fiction, and it’s about as realistic as Jessica Rabbit’s measurements.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jane Jacobs discussed the alleged conspiracy in her 2004 book “Dark Age Ahead.”

LikeLike

Michael

LikeLike

In a spirit of historical accuracy I posted a reply to Mr. Marsak’s article on the “Streetcar Conspiracy” at https://www.pacificelectric.org/los-angeles-railway/bunkerhilllosangeles-com-no-everyone-there-was-no-los-angeles-streetcar-conspiracy/. None of the mistakes I identify undermine Mr. Marsak’s argument in the least, but his exposition would have been cleaner without them. Am I being “fetishistic?” Is pointing out an error equivalent to omitting an extraneous fact? (To follow Mr. Marsak’s own example.) Not to my way of thinking. Everyone needs an editor.

LikeLike