So, there’s much movement afoot regarding Cooper Donuts, and as I have covered that topic at length (this then this then this), it seems only fitting we dive back in, with these two things:

1. The City of Los Angeles is voting tomorrow to name Second and Main “Cooper Donut/Nancy Valverde Square,” and 2. there was a piece in the New York Times yesterday about the whole business. Let’s look at both!

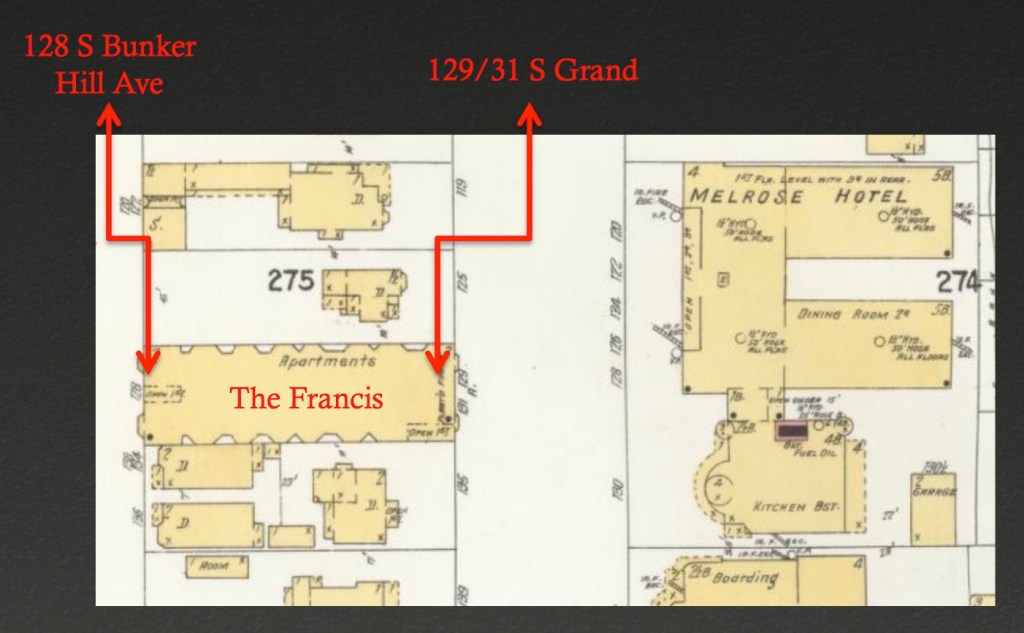

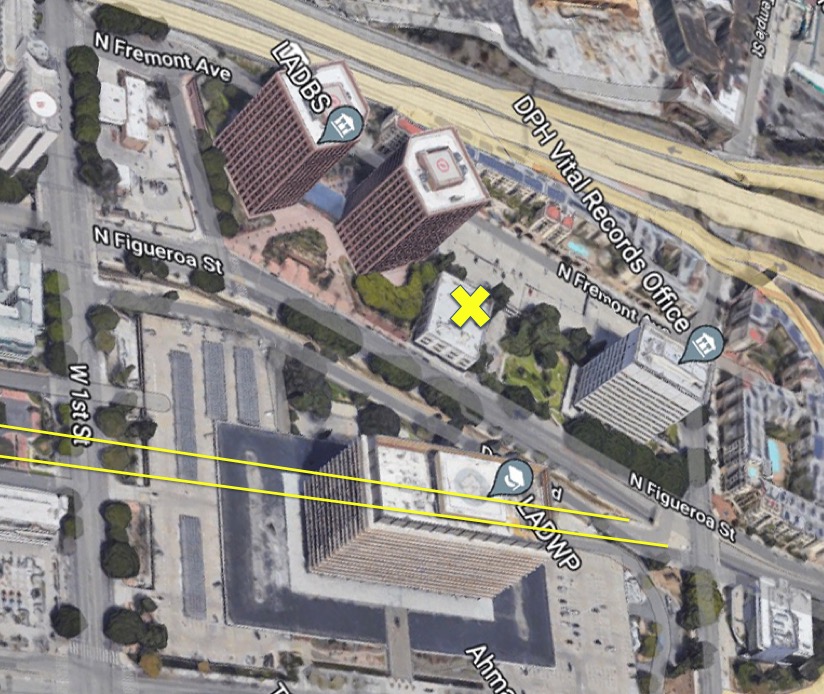

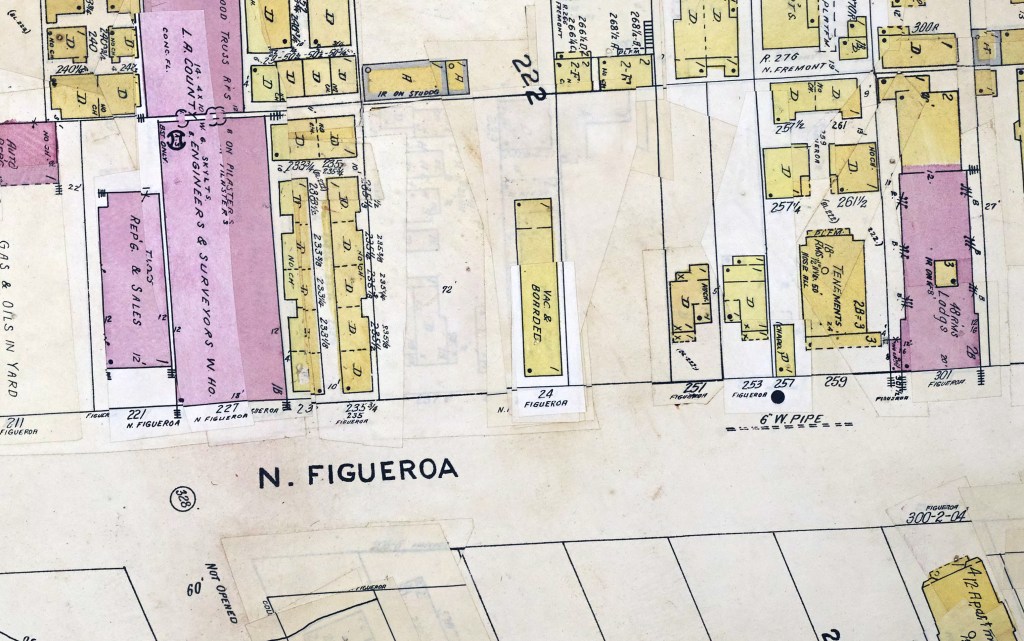

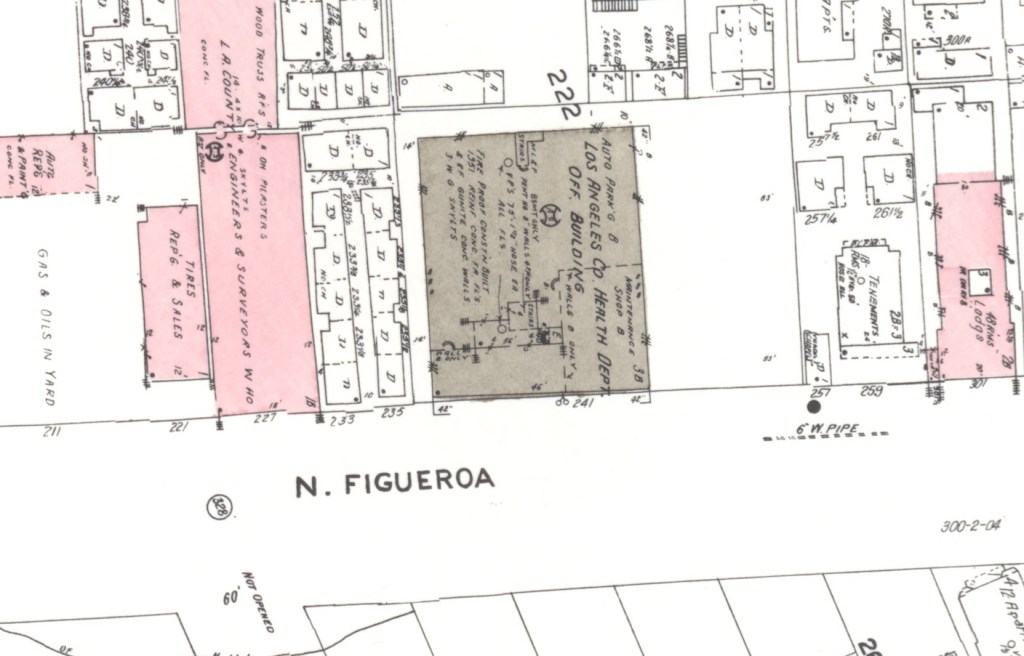

The idea of naming the square dates back to December 2021. That’s when it was only supposed to be Cooper Donuts Square. The contention being, that the Cooper Donuts at 215 South Main was the location of the famed 1959 uprising, the “first known instance” of “significant rebellion”.

However, as I have pointed out before, that is absolutely impossible, for two very good and simple reasons. You will recall, there is but a single, lone account of the riot—the one from John Rechy. Rechy stated, in no uncertain terms, that it happened in the spring of 1958…or spring of 1959. But as City building records conclusively prove (borne out by phone books and City directories), there was no Cooper Do-nuts at 215 South Main during either of those times. And, reason number two, Rechy’s lone account (and thus that which constitutes the whole of canon on the matter) of the riot clearly states it happened in the 500 block of Main.

What’s galling is that now people are falsifying history to an even greater extent. For example, Wikipedia. Someone went in to the Cooper Riot page and changed it to be about 215 South Main.

So what our deceitful Wiki-editor did—over the course of ten minutes last April 21st—was add in the fairytale address, then realized it now wasn’t between Harold’s and the Waldorf (as had been stated in the only account of the event literally ever) and thus weakly reworded it to say it was “near” these bars. Three blocks away.

But look! you say. It must be true because there are footnotes!

Yeah, no surprise, none of those footnotes actually say anything about 215 South Main. Because no-one even deigned to entertain such fabricated notions until a few weeks ago, when some people got hot to pass a motion through City Council.

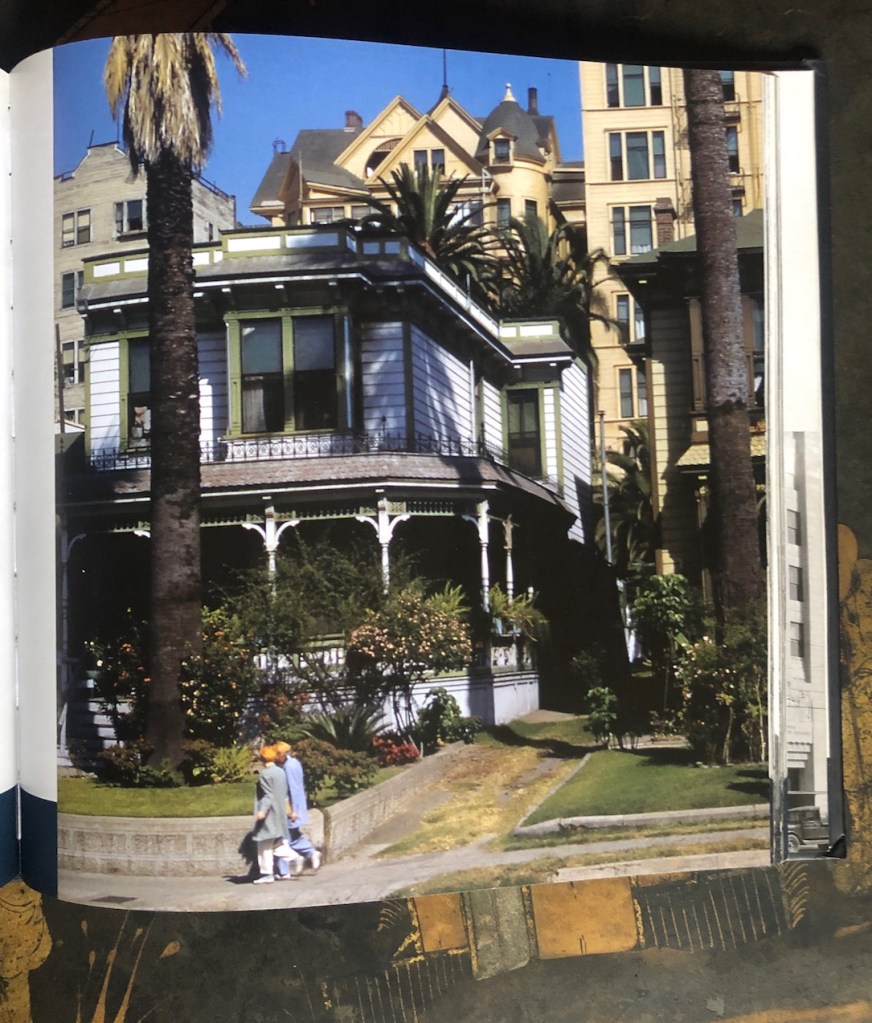

Ok, so we’re all on board that there was no riot there (or in any Cooper’s since the only witness/lone teller of the tale has said it wasn’t at a Cooper’s). Ergo, the focus has shifted—yes the riot is a myth, but no matter, now what’s important is that Jack Evans, who ran Cooper’s, was an ally, and that Cooper’s should be recognized as “being the sole safe place for all LGBTQIA+ persons regardless of gender expression” (as stated in the Community Impact Statement, link here)—though we’ll ignore the fact that Cooper’s at Second and Main was across from the Archdiocese and the Union Rescue Mission, inarguably a tough area for out trans people in the 1950s, who would be more welcome in establishments a few blocks south…which is why Rechy decided to place the story on Main down by Sixth Street in the first place. (I should mention that the nomination still, of course, contends “The first recorded instance in the LGBTQIA+ community of gender-transgressive persons resisting arbitrary police arrest occurred at Cooper’s Do-nuts at 215 S. Main Street in Downtown LA in 1959” which its Government Author certainly knows to be an egregious falsehood.)

We are told the nomination is important because Cooper Donuts was a “safe haven.” I believe Jack Evans didn’t turn away customers if they had money. That doesn’t make him an ally, that makes him a capitalist. Nevertheless, this guy—

—Jack Chester Evans, a middle-aged (b. 1907) white man from Lorenz, Iowa, we are told by the family, was an ally. Not that there weren’t allies back in the day, but they’re usually progressive Jewish lawyers, not this guy.

Apparently, there’s some deep and affecting story there about how and why Jack and his wife, Colorado-born Marge, were America’s most unlikely allies during the days of the Boise Panic and the blacklisting of Frank Kameny. Seriously, what formative moment occurred in Jack’s life to make him an ally of unparalleled bravery? We want to know!

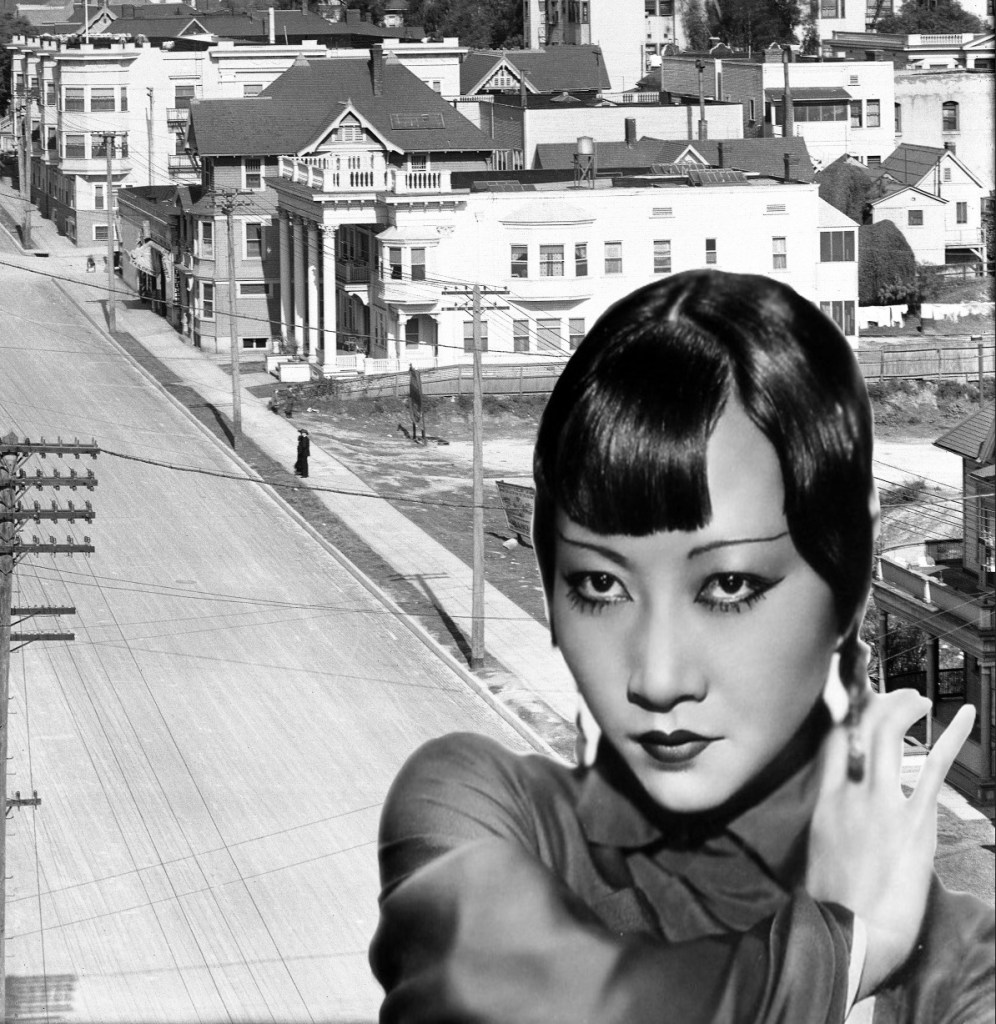

Recently, when the nominators of Cooper Donuts Square realized the whole Cooper story was pretty thin, they tied Nancy Valverde to it. Nancy is frequently mentioned as “proof” the riot happened, though it wasn’t until 2019, when asked about the subject by Los Angeles Magazine, she suddenly recalled that sixty years ago, she had heard second hand that something had happened somewhere. No matter; what is important, we’re told, is that she went to barber school near to the Cooper Donuts, had short hair and wore men’s clothes, and was welcome at Cooper’s (where she was particularly fond of the glazed donuts).

Now, I have no problem with a Nancy Valverde square, given as she is a famed activist and was trailblazing as an out lesbian in 1950s Los Angeles. But Second and Main? Really? Consider:

We are told in the City’s Community Impact Statement she went to Moler Barber School on Main near Third Street. That said, according to the Los Angeles LGBT Center, Valverde actually didn’t go to barber school: “getting her barbers license was an uphill battle, similar to the rest of her life. She was unable to go to barbers school because she didn’t finish school. However, one day, a man came up to her and told her that if she passes an IQ test, she could get her barbers license. After a lot of hard work, she passed her IQ test and became a barber.”

Also, she was arrested repeatedly for being butch. (And yet, she was accepted at Cooper’s!) “Valverde liked to look dapper when she was young. She purchased men’s slacks and button down shirts and got them tailored to fit her slender frame (from here).” I find it a little odd she was arrested repeatedly for just that, in that there was a fad for 1950s women looking boyish in general. Anyone with even the most rudimentary knowledge of women’s fashion, knows that post-1947 Bold Look into the 1950s, even the most vanilla housewife began wearing trousers with button-down shirts, and cutting their hair short; pixie cuts (and the less severe “Italian Cut”) were all the rage, e.g. Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn during the time—up to including my own mother who, 22yo in 1959, had short hair and dressed quite boyish, as was distinctly à la mode.

Point being, Valverde would have been accepted at Cooper’s because…why not? Women looking like boys was pretty common, but what Rechy specifically calls out is that boys in tight capris and midriff shirts were the picked-upon donut patrons: it would have been a lot easier for Valverde-in-trousers to go fetch herself a donut, rather than some transgressive boys, especially at a Cooper’s directly across from St. Vibiana’s and the Rescue Mission.

And yet Valverde was arrested repeatedly under LA’s arcane 1898 anti-masquerading law, Ordinance 5022…before she and her attorney overturned that law in court! But what raises an eyebrow is there’s never any evidence of when or how this happened. What date? What court? What judge? This would be a matter of public record down at City Archives, but I’ve got enough to do without going down to Piper Tech to find out. Someone please write me and give me the details, because I’d really like to know. I mean, for example, here it states she overturned the law in 1951. And yet, here it states she overturned the law in 1959. Well? (Protip: she was in fact never arrested under, and neither challenged nor overturned, anything called “Ordinance 5022,” despite what the City’s nomination states; 5022 didn’t exist after 1936, having been renamed Municipal Code 52.51.)

As I’ve said, I’m all for recognizing Valverde, but she didn’t spend much time at Second and Main, when she (perhaps) went to barber college at Third and Main. It seems like the Law Library, or more to the point, her barber shop on Brooklyn Avenue where she was hassled by LAPD, would be more deserving of a plaque.

Nevertheless, despite all this, when City Council votes to name Second and Main “Cooper Do-nuts/Nancy Valverde Square” on Wednesday, I have NO doubt it will be passed unanimously (just as it was passed unanimously by the Board of Public Works a few days ago). Despite conclusive proof there was no Cooper’s remotely near that corner during the time of the claimed uprising, atop the fact that the only witness said it didn’t happen there anyway; despite reasonable doubt that Cooper’s was “the sole safe place for all LGBTQIA+ persons regardless of gender expression” (Jack Evans an ally? And besides, we do have evidence of what Cooper patrons looked like in 1959, and I’m not seeing a lot of midriffs and capris); and man, this whole newly-tacked-on Nancy Valverde bit is kind of just “well, we have to put a Nancy Valverde plaque somewhere, this location is as good as any, I guess.”

II.

As I mentioned above, there’s an article in yesterday’s New York Times about Cooper Donuts. I’m in there! There’s not much I really need to add, that isn’t covered in the above.

Wellll, except it seems there’s always one more piece of information that requires commenting upon…like some bizarre whack-a-mole of “alternative facts.” See near the end of the NYT piece, where it mentions there was a Cooper Donuts at 243 East Fifth? And then links to Cooper Donuts Instagram post?

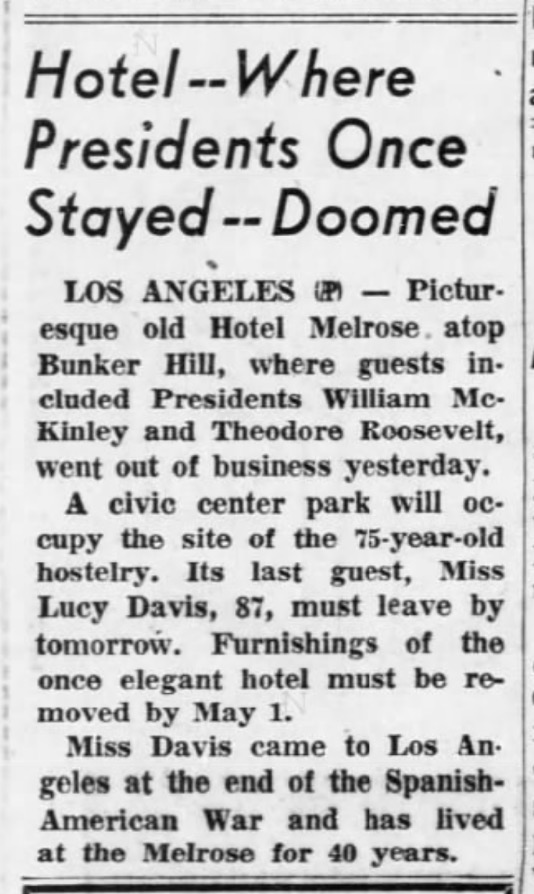

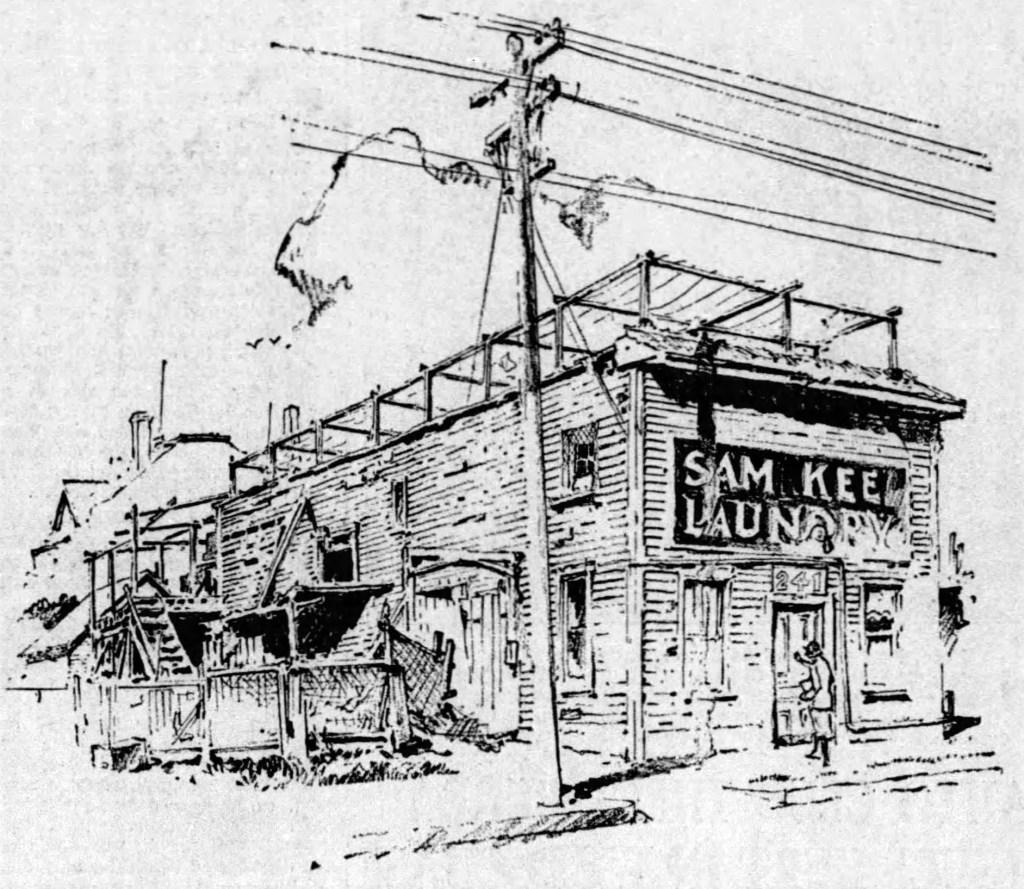

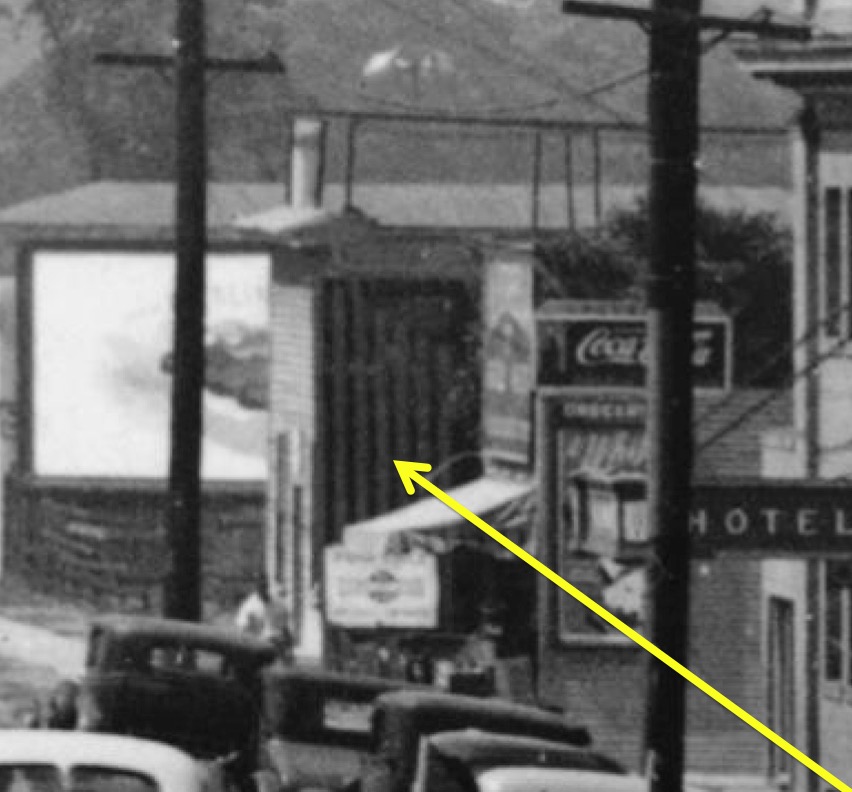

So, there was an Evans Cafeteria (it was never a Cooper’s Donut) at 243 East Fifth, and it was only there briefly. 243 became an Evans Cafeteria in 1953, and remained so for three years until that location went out of business in mid-1956 (the space thereafter became a bar called the Pioneer Cafe). “This site was a place of refuge for the LGBTQ community, and a symbol of resistance against police brutality and oppression.” Um, what? How? While I don’t have a shot of 243 East Fifth in its brief stint as a Cooper’s pre-1956, here’s 243, converted from a Cooper’s to the Pioneer Cafe, in 1959:

On a related note, here’s an interesting tidbit: we’re supposed to believe anything Jack Evans touched equals #LGBTsupporter and #LGBTrights because he was a trailblazing ally (again, on that we have no evidence, and have to take the family’s word on the matter). But we can say this with certainty, Jack Evans sure didn’t care much for unions and union workers!

It mentions his Evans Cafeteria at 215 and, note final sentence, the associated address of aforementioned 243 East Fifth, i.e. Fewster’s “Picketed by the AFL” Cafeteria, before its three-year stint as an Evans Cafeteria. Fewster’s is also associated with Jack Evans: Fewster’s Cafeteria was the establishment of Louis Dufferin Fewster, Jack Evans’ brother-in-law, which is how Jack took over the lease in 1953.

III.

While I have you here, let’s address the elephant in the room. You know, where you say “why is this Marsak guy being such a JERK?” Look, it’s not my fault people are altering Wikipedia with lies and I have call them out on it. Seriously, I don’t want to be the guy righting repeated falsehoods all the time; I did it two years ago with one blog post (because it was related to Bunker Hill), pointing out the impossibility of the tale, and other people keep doubling down to insist it’s true, so the thing keeps snowballing.

In yesterday’s New York Times piece Rechy states he was was weary of the “baffling hostility that has persisted” around his account, calling it “undeserved, incorrect, malicious, infuriating and, yes, saddening.” Really? I’ve no doubt you’re infuriated and saddened, but, the only account that’s incorrect is yours, sir. Simply searching for objective reality, utilizing empirical over anecdotal evidence, and relying on discoverable facts about this tale is assuredly not undeserved, and there has been—anyone and everyone will admit—nothing malicious or hostile about it.

Apparently, though, doing research is HATE. Let’s look at some other typical reactions to my having poked at the story:

Note in the first sentence: should you question the establishment narrative, you are part of an “activist hate group.” So, said activist hate group consists altogether of me, which is kinda rich (since as a short Jewish tweedy historian I don’t exactly come off as a skinhead or whatever), and my pals Kim & Richard of Esotouric, whose politics are ultra-progressive Left (and who I might add have a upcoming tour about Gay downtown LA). Plus no one has in any way tried to “stop” the nomination or monument process. My job as a historian is digging up the truth; what you do with the truth is your business. That you choose to ignore, or worse, deny it, is rather telling.

Another typical comment:

Note the bit “Some armchair historians have claimed that the Cooper Donuts couldn’t have taken place, but we have multiple accounts of people, like Nancy Valverde, who know of the riots and serve as proof that such an action did occur.” First of all, “armchair historian” is pretty funny, since I’m literally a historian, and have never been anything else (resulting in far too many phonebooks). But whatever, more importantly, when Mr. Zappia states regarding Cooper Donuts “we have multiple accounts of people, like Nancy Valverde, who know of the riots and serve as proof that such an action did occur” I would counter (and I hate to sound like a broken record, but) no, you don’t have multiple accounts, you have zero accounts: there was a) Rechy, lone and sole witness who told the (impossible/improbable for so many reasons) tale 45 years after its alleged occurrence and who then flatly stated “there was no riot at Cooper’s”; and b) Valverde, who wasn’t there, but sixty years after it purportedly happened and was pressed on the matter, at which point remembered she’d heard second-hand that something had happened, with no mention of Cooper’s. Those are, strictly speaking, the opposite of “proof.”

IV.

I love two things: history, and downtown LA. People are running about abusing both, so it’s only natural I’d try and right those wrongs. If I’m the one who’s wrong, well, no-one has even made so much as an single effort to refute my claims. Rather, they want to say that I “hate” because they feel like I should be wrong. But the fact is, history matters, and when you build it upon a specious, spurious foundation, it makes the whole thing stink.

Some stories don’t stink. Why not, for example, monument the site of Blanchard Hall, which is *actually* documented? What about the Crenshaw Women’s Center? Well the City is super hot to tear it down, so they’re tearing it down.

What about the two sites associated with gay civil rights activist Morris Kight? 1822 West Fourth, for example, would be a great monument, except developer-lovin’ YIMBY Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez is especially active in the fight to TEAR IT DOWN. Kight’s McCadden address might have a chance, though. Unfortunately for it, it doesn’t have the sex appeal of men dancing and singing in the street and making hardened Parker-era cops flee in terror.

Again, I am quite certain the motion will pass through Council tomorrow and the corner will be our newest monument. What’s troubling—besides our society’s wanton general disregard for truth—is that this monument will forever have the stain of falsehood upon it. All the good intentions in the world do not make confirmation bias, and an ad nauseam repetition of fake news, into reality. And then calling critical thinking and fact checking “hate” is an ugly way to shut down those who question the dominant narrative.

But, now it’s a monument, and you, having read this post, know the truth. Accuracy and fact being as useful as a chocolate teapot in this town, so, enjoy your new monument not to truth, but to truthiness.